Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout these days of mystery devoted to aspects of the painter’s life, art and legacy. The fifth instalment, Tom As Rock Star, takes a cross-disciplinary look at how the painter continues to influence Canadian arts and culture. I also compare Thomson to American writer Henry David Thoreau, on this day, the bicentenary of his birth.

I dreamed: of trout-fishing; and, when at length I awoke, it seemed a fable, that this painted fish swam so near my couch, and rose to our hooks the last evening — and I doubted if I had not dreamed it all.

In wildness is the preservation of the world.

— Henry David Thoreau

…Tom is a remote and mystical figure that broke into the artfirmament with a sudden and dazzling brilliancy, and then disappeared as suddenly into the unknown….

— A.H. Robson (1937)

Tom Thomson was Canada’s first rock star. Not because he had formal vocal training and played the violin. Not because he enjoyed plucking his 12-string Gourd mandolin around the campfire after a day’s painting and/or fishing.

He was Canada’s first rock star because he enjoys the fame — and suffers the notoriety — of rock stars in our tabloid celebrity culture. Moreover, the man and his art cast a shadow far beyond the visual arts, encompassing a broad range of Canadian popular culture.

If Tom as rock star is too much to bite off. Let’s concede, at the very least, he’s a pop phenom — in contemporary parlance — which is saying something in our obsessive youth culture.

Add elements of legend and hero worship to the web of fame and notoriety and you end up with an artist enmeshed in a tangled garden of mystery and martyrdom, myth and mystique. And this doesn’t take into account the most significant factor of all — his creative genius.

Thomson is our most (in)famous visual artist. When you consider the negligible role fine art plays in the lives of most ordinary people, it’s amazing what he represents in the minds and hearts of Canadians, many of whom know little, and care even less, about art.

Whether his body rests beneath the shores of Canoe Lake, where his corpse was found, or in a church cemetery in Leith, outside of Owen Sound where he was raised, he remains buried deep in this country’s collective consciousness.

No wonder secular pilgrims visiting his grave site(s) practice the ritual of leaving personal mementoes behind in the artist’s honour. (My angling buddy Dan leaves an artificial fly, usually a Mickey Finn streamer, so-named by the late humorist/journalist Greg Clark), whenever he visits the artist’s grave(s) or memorial cairn in Algonquin Park.)

Wherever he lies, Thomson’s final resting place is where the tributaries of fine art and popular art flow into the great Northern River of Canadian culture.

No Canadian artist in any discipline has been re-invented or re-imagined more. Quintessentially Canadian, his pictures are not only works of art, but national icons, symbolic of the mythic power of Wilderness and Nature — the Great White North, even though his painting was confined to southern Ontario in strictly geographical terms.

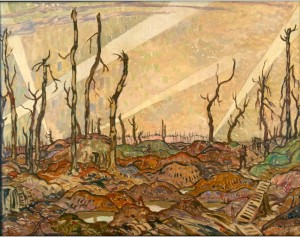

The myth-making machinery began upon his death when friends who formed the Group of Seven three years later transformed Thomson into The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Martyr. It helped that his death a few weeks before his fortieth birthday paralleled the slaughter of tens of thousands of Canadians in the gangrene-infested trenches of Europe.

The young writers, composers and artists killed in the First World War is enough to make the toughest heart weep. We speculate how Thomson’s art would have evolved had he not died when his painting was still in its formative stage; not to mention how his development would have influenced the direction of Canadian art.

Such conjecture is magnified when we reflect on how modern art across endeavours would have developed had the artists survived the so-called Great War. It’s staggeringly sad to contemplate.

A shocking number visual artists perished on both sides of the battle line: Isaac Rosenberg and Nina Baird from England; Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and poet/art critic Guillaume Apollinaire from France; Franz Marc and August Macke from Germany; Umberto Boccioni and Antonio Sant’Elia from Italy; Egon Schiele from Austria.

A generation of English poets was hit hard: Rupert Brooke, who famously visited Canada; Edward Thomas, close friend of Robert Frost; and Wilfrid Owen. How Owen would he would have influenced the trio of modern titans Pound, Eliot and Yeats is anyone’s guess. Canada lost John McCrae, the Guelph physician, surgeon, artist, author and poet whose In Flanders Fields remains one of the most enduring poems from the war.

Listen to A Shropshire Lad, The Banks of Green Willow or the English Idylls and you wonder whether George Butterworth would have joined Granville Bantock, Frank Bridge, Frederick Delius, Edward Elgar, Gerald Finzi, Gustav Holst, Percy Grainger, Hebert Howells, John Ireland, Hubert Parry, Charles Stanford and Ralph Vaughn Williams in the upper echelon of English music.

In light of such awful artistic carnage, it’s understandable why there’s so much anxiety aroused by Thomson’s non-military status. Did he try to enlist, not once but twice? Was he rejected as medically unfit? Was he a pacifist who sought refuge in the near wilderness of Algonquin Park? Was the war in some way responsible for his death?

Some of the artists who subsequently formed the Group served: A.Y. Jackson and Fred Varley as war artists overseas, as well as Lawren Harris who enlisted and eventually suffered a nervous breakdown.

The death toll in the war reputed to end all wars is a terrible story. But artists dying young have always bathed in a glow of bittersweet what ifs. The Romantics were as obsessed with death almost as much as they were nature. There’s the trio of English poets — John Keats, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley — as well as French poet Arthur Rimbaud.

And the three Bronte sisters — Charlotte, Emily and Anne — who died young (two other sisters died in childbirth). In the world of classical music there’s Franz Schubert.

Last century witnessed the deaths of prominent writers and artists, both young and in their prime.

The deaths of Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol, artists at the pinnacle of fame, unsettled the American art establishment. Troubled Welsh poet Dylan Thomas died unexpectedly in America. Like Thomson, he was forever young at 39. American poet Sylvia Plath’s suicide stalked her poet-husband Ted Hughes to the grave.

More recently we have the suicides of promising American novelist John Kennedy Toole and wunderkind author David Foster Wallace.

Pop culture has its own sad story. Billy Joel wasn’t the first to observe that, ‘only the good die young.’

In the wilderness of cultural celebrity, death in artistic prime fuels high-octane legend, whether James Dean, Buddy Holly, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Townes Van Zandt or Tim Buckley and son Jeff (both of whom died by drowning). More recently we have Kurt Cobain; earlier we had Hank Williams and Woody Guthrie. Before that there was bluesman Robert Johnson and jazz trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke.

I sometimes think of Thomson in relation to Gram Parsons, the country rock pioneer who mentored Emmylous Harris, Flying Burrito Brothers, The Byrds and The Eagles. He died young and, in accordance with his wishes, his corpse was spirited away and burned in the desert at Joshua Tree, fanning the flames of rock legend.

Hamilton’s Daniel Lanois produced U2’s Joshua Tree, one of the great rock albums of the last quarter of the last century, as homage to Parsons. He also produced Harris’ seminal album Wrecking Ball.

I have even heard Thomson’s death spoken in the same breath as tortured genius Vincent van Gogh, not to mention the assassinations of the three great American leaders from the 1960s — John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King. This is ridiculous hyperbole, but secular canonization challenges the bounds of reason and common sense.

Celebrity currency is inflated by the intimate link of art with violent death — whether misadventure, murder or suicide.

Had Thomson slipped and hit his head on a rock while getting into his canoe or tumbled and struck his head on a paddle or gunwale, thwart or yoke while standing in his canoe to pee, his death would be a footnote rather than a headline to his life story. There would be no mystery; just a mildly interesting personal narrative.

Of course, we have the art irrespective of biography. We always have the art.

I contend that, had Thomson not lived, Canadians would have invented him. His disappearance, death and burial remain shrouded in whispered rumour, innuendo and gossip. The speculation provides imaginative space in which to construct legend and myth.

When his bloated and decomposing body was discovered floating in Canoe Lake eight days after disappearing on July 8, 1917, circles of silence spread like outwardly expanding ripple rings after a fishing lure hits the water. Residents on the lake, family and friends, the artists who formed the Group of Seven and patron Dr. James MacCallum all had self-serving interest in protecting Thomson’s reputation and safeguarding his legacy.

On a personal scale, Thomson remains a blank canvas on which we paint our portraits of the artist; or expressed another way, a blank page on which we write our descriptions of the artist. Whether through word or image, we incorporate him into our own narratives.

Thomson’s celebrity has undoubtedly influenced his value on the auction block in recent years. For, however successful scholars and critics are in securing the painter’s place in the history of Canadian art, academic legitimacy can’t subordinate our obsession with how, when, where and why he died.

How else to explain a small oil a few years back demanding $170,000? Sure the painting had never been seen in public. And the Canadian art market was bullish. But, really, almost two hundred grand for Boathouse, Go Home Bay, a small, hastily executed board — more a sketch in oil than a painting — the artist gave to a 10-year-old girl as a gift.

The auction provided the kind of promotion money can’t buy for Tom Thomson, the first comprehensive Thomson exhibition in more than three decades co-presented by the National Gallery of Canada and Art Gallery of Ontario in 2002.

The market for Thomson remained bullish after the major retrospective. In November, 2009 a large canvas from 1917 attracted a bid of $2.35 million ($2.75 million including the premium). Early Spring, Canoe Lake set a record for the artist at auction and almost tripled the pre-sale estimate.

A few days earlier, Winter Morning, a forest landscape with trees blanketed in snow featuring notations on the back, sold for $973,000 including an 18 per cent buyer’s premium. The back of the 21×27-centimetre painting had a title and signature, a rarity for Thomson. The sale price marked it as one of the 10 highest prices ever achieved at auction for works by the painter.

To my mind, Thomson’s death links him to a couple of quintessentially Canadian artists who died prematurely and, in the process, are shrouded in the garb of legend and myth.

Stan Rogers, who perished in an airplane fire in Cincinnati in 1983, has enjoyed more fame since his death at age 33 than during his lifetime. The myth-makers forget he was a marginal figure outside of North American folks circles, where he was held in high esteem. The legend of Stan Rogers is a posthumous construct — a fact his younger brother Garnet recorded in his haunting song Night Drive and later detailed exhaustively in his memoir Night Drive: Travels with My Brother.

Rogers’ posthumous fame and adoration echoes Thomson’s. The People’s Folksinger shares much in common with the People’s Painter.

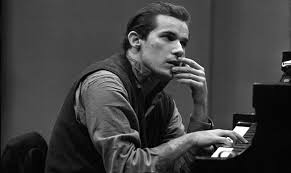

Although Glenn Gould enjoyed an international reputation when he died in 1982 at the age of 50, his eccentric and reclusive nature, awkwardness around people, powerful sex appeal coupled with apparent sexual ambiguity, obsessive-compulsive nature, mystery surrounding his life and death and affinity with the Canadian North connect him to Thomson in terms of ‘sympathetic imagination’, to use Northrop Frye’s phrase.

Gould’s thoughts on the North were influenced by Thomson and the Group. His ‘sound documentary’ The Idea of the North was commissioned by CBC and aired in 1967. As it was for Thomson, the North for Gould was a metaphor for the essence, the spirit, of Canada. Like creative explorers, the painter and the pianist charted the geography of the imagination.

Interestingly, Thomson and Gould were portrayed as creative ascetics by early biographers. However, recent biographies — Roy MacGregor’s Northern Light and Michael Clarkson’s The Secret Life of Glenn Gould — report of active sex lives.

Moreover, reading Clarkson’s descriptions of Gould often sound like Thomson: ‘he was a mysterious dreamer… he would launch himself into the eye of the storm and turn it into paradise….’ Clarkson’s description of Gould as ‘a lone wolf’ fits the painter perfectly.

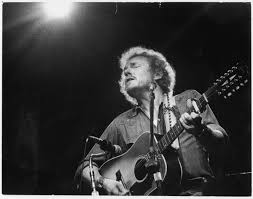

Thomson’s inspiration and influence resonate throughout the spectrum of Canadian popular music. It’s hard to imagine Gordon Lightfoot, Ian Tyson, Bruce Cockburn, Murray McLauchlan or Ian Tamblyn, among numerous others, paddling beyond the forest of symbols into the mythic landscape without the painter as wilderness guide.

I think of Thomson and Lightfoot as creative soulmates who define Canada for those who live here, as well as those who live elsewhere. Like Thomson, Lightfoot is an awkwardly shy introvert from small-town Canada who spent a short period in the U.S. before returning home and building his art by drawing inspiration from the Canadian landscape. Both shared a love of canoeing and a love of whiskey.

More significant, Lightfoot’s searing artistic vision of the country, and the music it produced, is comparable to that of Thomson’s. And following the painter’s example, Lightfoot’s pictures in lyric and melody profoundly influenced all who followed. Both are seminal artists in our country’s rich cultural mosaic. Lightfoot achieves in song what Thomson achieved in painting. Both are equal among Canada’s artistic giants.

Like few other artists, Thomson and Lightfoot penetrate the primordial depths of this country’s ancient soul.

I can’t imagine a better way of experiencing that primeval splendour from an armchair — yes, from an armchair — than by pouring three fingers of Crown Royal’s Northern Harvest into a tumbler, putting Lightfoot’s Canadian Railroad Trilogy, Song for a Winer’s Night or The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald on the CD player and grabbing the largest coffee-table Tom Thomson book within reach and looking deeply at Northern River, The Jack Pine or The West Wind.

There was a time in this fair land when the railroad did not run

When the wild majestic mountains stood alone against the sun

Long before the white man and long before the wheel

When the green dark forest was too silent to be real….

and

The lamp is burnin’ low upon my table top

The snow is softly fallin’

The air is still within the silence of my room

I hear your voice softly callin’…

The smoke is rising in the shadows overhead

My glass is almost empty

I read again between the lines upon the page

The words of love you sent me….

and

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they called ‘gitche gumee’

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomy….

Like any rock star worth the title, Thomson has been fictionalized in song and drama, fiction and poetry — as have Rogers and Gould. He’s the most storied artist in our country’s cultural discography and/or cultural anthology. Thomson and the Group are primary subject(s) of numerous songs and albums crossing genres and styles:

- Former Toronto rock band RHEOSTATICS was commissioned to compose Music Inspired by the Group of 7 in conjunction with a retrospective organized in 1995 by the National Gallery of Canada in honour of the Group’s 75th anniversary. The band performed the music in front of projected paintings and period film footage. The recoding is mostly instrumental, with vocal threads featuring MacKenzie King, John Deifendbaker and hockey player Newsy Lalonde, in addition to West Coast landscape artist Winchell Price (who sounds like Lightfoot talking about painting landscapes).

- Toronto jazz composer/guitarist TONY QUARRINGTON recorded Group of Seven Suite in 2002. The West Wind is the opening of eight tracks. To my mind, the work recalls Oscar Peterson’s classic Canadiana Suite, recorded in 1965. What Thomson and the Group achieved with colour, texture and line, Quarrington achieves with melody, rhythm and tempo. He observes in liner notes that, ‘(Thomson and the Group of Seven) found a new way to look at the land, which forever altered, not only painting, but the way we look at the land….’ Exactly.

- TRAGICALLY HIP, the popular Kingston rock band anchored by vocalist Gord Downey, recorded Three Pistols on their seminal Road Apples album. It begins with the lines:

Tom Thompson (sic) came paddling past

I’m pretty sure it was him

- Like many of us, Ontario folksinger DAVID ARCHIBALD was introduced to Thomson and the Group in public school. In preparation of Northern River he spent time in Algonquin Park, visiting Thomson’s first (and perhaps only) burial site. A hybrid concert/folk opera written in 1980, its songs portray dramatic scenes from Thomson’s life, employing projected images (paintings and archival photographs) as a backdrop. It explores the notion that Thomson is a painter of dynamic conflict: city/nature, tame/wild, tradition/innovation, conservative/radical, solitary/community, war/peace.

- DAVID SEREDA first saw Thomson’s painting The Fisherman as a teenager in Edmonton. He worked on Songs in the Key of Tom over eight years in Owen Sound, writing the initial songs in 2002 as part of a community arts workshop, first performed at Tom Thomson Art Gallery. He expanded the concert into a musical in conjunction with Joan Chandler, artistic director of Sheatre. Both configurations are biographical journeys through song that present Thomson as a figure in which nature and culture are integrated. Moreover, both contend the mystery of Thomson is not how he died, but how he came to paint such accomplished pictures in five brief years. It’s a notion with which I agree.

- In the fall of 2016 SEREDA was joined in concert by Toronto Poet Laureate Anne Michaels, Keira McArthur, Tyler Wagler, Sandra Swannell and Juno-winning musician Ken Whiteley in a presentation of The Woods Are Burning (A Celebration of Tom Thomson). The concert combining music and spoken word (poetry, letters and readings) began outdoors and moved indoors as the natural light faded. ‘Tom’ roamed the ravines of Toronto while the performers pursued hot on his trail….

- Toronto multimedia artist KURT SWINGHAMMER released Turpentine Wind in 2010. Consisting of an audio CD and DVD of digital animations against a sonic backdrop, the song cycle spans spring through winter, with each season representing a phase of Thomson’s life. It traces the artist’s journey from Owen Sound to Toronto to the bottom of Canoe Lake. The companion BluRay disc features ambient remixes set to animations of digital recordings of his vocal tracks.

- MAE MOORE is a singer/songwriter, visual artist, environmentalist and organic farmer on one of British Columbia’s gulf islands. Her album Folklore is an exploration of inner and outer landscapes, featuring original artwork in the album package. The album was released in conjunction with a companion coffee table book containing 19 of her paintings. Her ballad Tom Thomson’s Mandolin begins:

Soft maple in autumn, a shift in the weather

Turn your canoe to the shore

We turn our eyes to where wild geese fly

Your landscapes live on evermore

Obviously we don’t celebrate Thomson for his singing, let alone violin and mandolin playing. Nonetheless, he’s the most famous of many Canadian artists and/or performers who straddle creative disciplines. A number of artists or groups of artists performed music that was appreciated within their own milieu including the brash macho-sophisticates associated with the Isaacs Gallery in swinging 1960s Toronto, Michael Snow (one-time husband of fellow artist/film maker Joyce Wieland) and London, Ontario’s Nihilist Spasm Band (members including over the years Art Pratten, Murray Favro, John Boyle, Aya Onishi, Bill Exley and John Clement, as well as the late Greg Curnoe).

Conversely, a number of singer/songwriters have enjoyed success as visual artists including Juno-winners Fred Eaglesmith and Eileen McGann, Mendelson Joe and the above mentioned Moore and Swinghammer, not to mention international stars Bryan Adams, Buffy Sainte Marie and Joni Mitchell, among others. (There’s a distinguished list of international musicians who are visual artists including Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Patti Smith, David Bowie, John Mellencamp, Marilyn Manson, Cat Stevens, Ron Wood, Ryan Adams, Tony Bennett and Miles Davis, to name a few.)

Thomson made it to the big screen in 1976 with the release of The Far Shore. Wieland’s feature-length art film painted Thomson with a romantic brush. Although a box office flop, the cinematic love story laced with cultural intrigue presents the painter as Artist Hero.

There have been numerous documentary films and TV docs on Thomson since the 1940s. A couple of the most recent are very good.

Director David Vaisbord and producer Ric Beairsto revisit the mystery surrounding the painter’s death in Dark Pines: A Documentary Investigation into the Death of Tom Thomson, a made-for-TV docudrama examining a range of familiar themes: love affair igniting bitter rivalry, political debate turning violent, secret gambling debt, haphazard investigation and exhumed body from a grave believed to be another man — all brought to life by actors playing historical characters.

My favourite doc is West Wind: The Vision of Tom Thomson, a White Pine Pictures film by Peter Raymont. The documentary focuses on Thomson’s life as an artist rather than his mysterious death. It addresses the question of how he became so good so quickly.

White Pine has produced excellent documentaries on Glenn Gould (The Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould), Emily Carr (Winds of Heaven) and Lawren Harris (Where the Universe Sings: The Spiritual Journey of Lawren Harris), as well as Painted Land: In Search of the Group of Seven, which explores locations that find expression in some of their most iconic paintings.

Except for its dramatic re-enactments, Painted Land is in many ways a cinematic version of Jim and Sue Waddington’s In the Footsteps of the Group of Seven, which chronicles half a century of searching for sites that inspired the painters’ images.

Tom as Rock Star appears in the flesh in Jim Betts’ folk operetta Colours in the Storm, which premiered in 1990. (London, Ontario’s Grand Theatre staged a revival this spring to commemorate the centenary of Thomson’s death.) It tells the story of Thomson’s life and art, revolving around his suspicious death six years after he began making annual trips to the provincial park in 1912.

Thomson didn’t become a landscape painter until the age of 34, a year before he began visiting the park that became the source of his inspiration and focal point of his production — not to mention spiritual home. The influence the park exerted on Thomson’s artistic development cannot be over-emphasized. Had he never visited, he most certainly would have never become the artist we celebrate a century after his death. Of course, he might have lived well into old age, unknown and forgotten like most of us.

It’s an intriguing coincidence that the centenary of Thomson’s death takes place during Canada’s sesquicentennial.

Windsor, Ontario playwright Barry Brodie decided to celebrate Canada’s birthday by acknowledging the passing of its national painter.

Four years in the making, The Threshold of Magic is a one-man show with song and music. It’s premier at the Art Gallery of Windsor featured Jeffery Bastien as the artist among a dozen supporting characters.

The play begins at the moment of Thomson’s death on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. Invited by a benevolent spirit/guardian, Ralph Waldo Emerson, to explore his life and art, the painter recalls the relationships and inspirations that contributed to his artistic production and legacy. Emerson was at the centre of the New England Transcendental movement in the mid-19th century. His most gifted student, Henry David Thoreau, was one of Thomson’s favourite authors.

The play examines the intersection of art, human relationship and nature. The audience gets an intimate look at an artist who drew inspiration from a deep appreciation of nature and, through increasing technical skill, sought to express the infinite through his art. Drawn from historical documents, as well as conversations with members of the Thomson family, the play puts flesh on the bones of an iconic Canadian.

In an interview with CBC Radio, Brodie said he was surprised there is so little dramatic work devoted to Thomson. Acknowledging the mystery that continues to dog the painter’s death, Brodie said he didn’t want to play the conjecture game. Instead, he places the painter in the afterlife as a means of exploring ‘his heart and his soul.’

Thomson didn’t leave behind much in the way of primary sources, including letters and recorded observations about his art, so Brodie relies on the people around him who encouraged and supported his art including family, friends, Grip Limited colleagues and fellow artists, especially Lawren Harris and A.Y. Jackson.

The play’s musical score is anchored by a series of songs written by Brodie based on poetry of the so-called Confederation Poets — Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carmen, Archibald Lampoon and Duncan Campbell Scott.

In conjunction with the play, Windsor’s Black Moss Press published On the Threshold of Magic, a collection of work compiled by Brodie on which his play is based. The play’s text is included.

Thomson was celebrated in classical dance in 2007 when Toronto’s Ballet Jorgen premiered Group of Seven Nutcracker, a ‘True North’ adaptation of the popular Yuletide staple originally choreographed by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov to music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Elements of the original ballet are preserved. However, it’s not an adaptation so much as a bold re-imagining. Artistic director/choreographer Bengt Jorgen and designer Sue LePage built the ballet around three paintings enlarged as scenic backdrops.

Frank Carmichael’s Church and Houses at Bisset establishes the setting. The ballet takes place in the village of Bisset, north of Algonquin Park, on Christmas Eve 1912. Thomson’s Snow in the Woods provides the atmospheric backdrop for the magical winter woodland scenes that complete the First Act. Late Group of Seven member LeMoine Fitzgerald’s Trees and Wildflowers provides the backdrop for the summer woodland scenes of the second act.

Jorgen goes beyond employing a trio of iconic Canadian paintings. The ballet brings to mind Louis Hémon’s classic novel of the land Maria Chapdelaine. Similarly, the young girl at the heart of ballet recalls Anne Shirley in Anne of Green Gables.

Although he retains the magical Nutcracker, Jorgen introduces a colourful cast of Canadian figures including a character based on Thomson amidst lumberjacks, trappers and Mounties who share the stage with foxes, skunks, wolves, owls, rabbits, beavers, frogs, dragonflies, bats, squirrels, chipmunks, raccoons, loons, deer, bats and trilliums, in addition to a giant spruce tree. There are scenes incorporating a sleigh pulled by white-tailed deer, as well as a birch-bark canoe — one of Canada’s great national symbols.

More recently Thomson has touched the world of classical music. Sonic Palette is a concert program created and performed by the Algonquin Ensemble, which was formed for the sole purpose of celebrating the painter’s work through original music and visual projection. The sextet consists of Kathryn Briggs (piano), John Geggie (double bass), Lisa Moody (viola), Laura Nerenberg (violin), Margaret Tobolowska (cello) and Terry Tufts (guitar hybrid).

The ensemble’s artistic goal is capturing the painter’s enduring spirit through the convergence of art and music. Original compositions for piano, guitar, double bass and string trio interpret Thomson’s life, art and legacy.

Some compositions are collages constructed on similar themes such as sunsets and log drives on Canoe Lake; other iconic paintings such as The Jack Pine and The West Wind inspired stand-alone musical tributes. While predominantly instrumental, a few vocal selections provide a biographical and contextual framework. The concert is performed against a slideshow backdrop of archival photos of Thomson’s life as well as his art.

As a seemingly inexhaustible subject, Thomson straddles a range literary genres: detective story, mystery, romance, gothic tale, ghost story, tragedy and portrait of the artist as a young man, not to mention poetry. This is in addition to the traditional genres of critical discourse: biography, memoir, travelogue, art history and cultural anatomy.

A number of Canadian poets have paid homage to Thomson including Douglas Barbour, Robert Kroetsch (who once described Thomson as the ‘archetypal Canadian artist’), Dennis Cooley and George Whipple, the latter of whom titled his selective poems Tom Thomson and Other Poems.

The most recent poetry collection inspired by the painter is Earth Day in Leith Churchyard: Poems in Search of Tom Thomson, by Bernadette Rule, a former professor of English at Mohawk College.

Following in the tracks of Marked By the Wild, an anthology of literature shaped by the Canadian wilderness published in the 1970s, Open Wild a Wilderness is the first anthology devoted solely to Canadian nature poems ever published. It could be dedicated to Thomson. Three poems refer to him by name – Dennis Lee’s Civil Elegy 3, Charles Lillard’s Little Pass Lake and Don McKay’s Precambrian Shield.

The anthology — published by Wilfrid Laureir University Press — confirms Thomson and the Group as threads connecting the chronological chain of Canada’s poets, from the Confederation Poets (Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carmen, Archibald Lampman and Duncan Campbell Scott), through Earle Birney, Frank Scott and Al Purdy, to Margaret Atwood and Gwendolyn MacEwen, and finally to McKay and the generation of eco-poets.

Troy Jollimore, a Canadian academic who teaches philosophy at California State University, won a National Book Award for his poetry collection Tom Thomson in Purgatory. Not surprisingly, American literary critics praised the collection without recognizing the significance of Thomson.

Here are two of my favourite poems not specifically about Thomson which, nonetheless, evoke a haunting sense of the artist. The final lines of Margaret Atwood’s poem Resurrection, from The Journals of Susanna Moodie:

(but the land shifts with frost

and those who have become the stone

voices of the land

shift also and say

god is not

the voice in the whirlwind

god is the whirlwind

at the last

judgment we will all be trees

I read Gwendolyn MacEwen’s poem Dark Pines Under Water, from The Shadow Maker, as an elegy for Thomson:

This land like a mirror turns you inward

you become a forest in a furtive lake;

The dark pines of your mind reach downward,

You dream in the green of your time,

Your memory is a row of sinking pines.

Explorer, you tell yourself, this is not what you came for

Although it is good here, and green;

You had meant to move with a kind of largeness,

You had planned a heavy grace, an anguished dream.

But the dark pines of your mind dip deeper

And you are sinking, sinking, sleeper

In an elementary world;

There is something down there and you want it told.

Thomson paddles through the pages of fiction, both young adult and adult.

Larry McCloskey’s mystery Tom Thomson’s Last Paddle features a couple of adolescent girls reminiscent of Nancy Drew or Hardy Boys. Thomson’s ghost plays a prominent role in solving the mystery of his own death.

Neil Lehto, a Michigan lawyer who made annual canoe trips to Algonquin Park for years, became fascinated with Thomson. Algonquin Elegy is a fiction/non-fiction hybrid, equal parts historical crime novel and contemporary romance. Subtitled Tom Thomson’s Last Spring, it traces parallel stories: the mystery of the painter’s death and a love story involving a man recovering from his wife’s suicide.

Roy MacGregor is a special case because he’s written fiction, memoir and non-fiction about Thomson. Whether we agree or disagree with his interpretations and opinions, readers interested in Thomson cannot ignore this prominent journalist/author.

Originally published in 1980 and reissued in 2002 in trade paperback as Canoe Lake, Shorelines tells the story of an orphan who visits a fictional village resembling Huntsville to seek out her mother and deceased father – you guessed it, thinly disguised fictional portraits of Winnie Trainor and Thomson, who Macgregor and others, but not all, allege were lovers.

MacGregor addresses the supposed romance between the painter and Trainor, a distant relative through marriage, in Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him. The provocative non-fiction/memoir stirs the pot of controversy, placing Trainor centre stage in the romance. MacGregor speculates that the two were not only lovers, but the painter fathered an out-of-wedlock child with the young woman from Huntsville. En route he corrects some historical errors and sets out to resolve the mystery of where the painter is buried.

A quintet of his works of non-fiction — A Life in the Bush, Canoe Country, The Weekender, Escape and Canadians – while not about Thomson, offers insight into the world the painter inhabited in Algonquin Park.

Thomson and the Group have helped shape numerous critical works and cultural studies not specifically about the visual arts. Those indebted to the painter deserve their own blog posting. While too numerous to delineate, a few hold special interest for me.

Thomson’s spirit permeates a tradition of literary commentary and cultural discourse led by the intellectual giant Northrop Fyre (The Bush Garden), not to mention such ‘small frye’ as Margaret Atwood (Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature and Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature) and D.G Jones (Butterfly on Rock: A Study of Themes and Images in Canadian Literature), Dennis Lee (Body Music), Tom Marshall (The Harsh and Lonely Land), Susan Glickman (The Picturesque and the Sublime: A Poetics of the Canadian Landscape), Margaret Northey (The Haunted Wilderness) and Eli Mandel (Another Time), among others.

One of the 20th century’s most influential literary critics, Frye wrote a number of essays on Thomson and the Group. He was the first to observe that Thomson’s sense of design is ‘derived from the trail and the canoe.’ However, the painters challenge the critic’s celebrated notion of the wilderness as a source of terror against which pioneers constructed a garrison mentality — a notion that subsequently influenced Atwood’s premise of survival in a harsh, threatening wilderness.

Interpreting and evaluating the many critical studies on Thomson or the Group is beyond my scope here. However, I would like to mention a trio of significant recent works.

In 2004 Sherrill Grace, an English professor at the University of British Columbia, published Inventing Tom Thomson, a full-length critical study. Subtitled From Biographical Fiction to Fictional Autobiographies and Reproductions, it’s a provocative (feminist criticism on steroids) examination of the various ways Thomson’s biography, factual as well as imagined, continues to overshadow his art. Her previous study, Canada and the Idea of the North, published in 2002, is also relevant to an appreciation of Thomson.

For my money Ross King’s Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven is the best general study of Thomson and the Group. The critical biography discusses the painters in terms of international artistic trends and styles. It’s a lucid synthesis of the research conducted by art historians and curators. In addition, it discusses the painters in the context of larger social, political, historical and intellectual forces from the Victorian era through the Great Depression, with special reference to WWI.

In the final pages of Defiant Spirits, King laments that Thomson and the Group are ‘in danger of slipping from the public imagination.’ No chance. On the strength of major exhibitions mounted in major galleries in the early days of the new millennium, both here and abroad, along with important books that have been published, I think King greatly exaggerates the painters’ deaths (to paraphrase a quote erroneously attributed to Mark Twain). Like deer in headlights on a northern highway, Thomson and the Group are as much in the public glare as they’ve ever been.

Gregory Klages’ The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction surveys all the books and available archival documentary material with the intent of shedding light on the myriad mysteries that cloak the painter in dark intrigue. I have said elsewhere that the book is required reading for all Thomson fans.

The impact of Thomson’s legacy on the development of Canadian art after his death is a subject worthy of separate treatment. However, I would like to offer a few impressions and observations with respect to selected artists. As an influence on subsequent artists, Thomson runs the rapids of two parallel rivers: his impact based on actual practice and production and speculation about the artist he would have become had he lived into maturity.

Had Thomson not been so talented and demonstrated so much potential, the gossip and conjecture surrounding his life and death would not have maintained such a tenacious grip on the collective imagination of Canadians. He didn’t reach his artistic stride until he was 35 after a decidedly unspectacular apprenticeship. As mentioned above, this coincided with his first trip to Algonquin Park in 1912, after which he enjoyed a brief five years of rapid and continuous growth — really extraordinary growth.

All of which fuels speculation about what kind of painter he would have become had he lived his Biblical three score and ten. Would he have paddled ahead of his more ‘conservative’ creative companions, who became the Group of Seven? Would he have portaged into abstraction, like his close friend Harris, or ventured from landscape into one of numerous isms that came to define art in the 20th century?

As it was, Thomson and the Group cast the mould for a number of influential groups of mostly male artists who changed the landscape of Canadian art over the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s including:

- Montreal’s Automatistes in Montreal (Paul-Emile Borders, Marcel Barbeau, Roger Fauteuil, Claude Gauvreau, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Pierre Gauvreau, Fernand Leduc, Jean-Pierre Mousseau, an females Marcella Ferron and Francoise Sullivan).

- Toronto’s Painters Eleven (Jack Bush, Oscar Cahen, Tom Hodgson, Jock MacDonald, Ray Mead, Kazuo Nakamura, William Ronald, Harold Town, Walter Yarwood and females Alexandra Luke and Hortense Gordon).

- Toronto’s Isaacs Gallery artists (Robert Markle, Dennis Burton, Graham Coughtry and Gordon Rayner).

- Regina 5 (Kenneth Lochhead, Arthur McKay, Douglas Morton, Ted Godwin and Ronald Bloore).

- London, Ontario’s Forest City artists in London, including Jack Chambers, Greg Curnoe and Tony Urquhart.

Most of these artists pitted themselves against the ‘conservative’ artistic legacy of Thomson and the Group, which is to say, representational landscape. The exceptions were Town and Markle, both of whom nurtured a creative relationship with Thomson.

The flamboyant Town and art historian David Silcox co-wrote The Silence and the Storm. Published in 1977 in honour of the centenary of his birth on Aug. 4, 1877, it was the first significant critical study of Thomson’s art. An expanded reissue is being released this fall, just in time for Christmas. With 70 never-before-published reproductions and new essays to complement the original text, it’s being billed as ‘the most comprehensive collection of the artist’s work ever published.’

The Isaacs Gallery artists defined urban hip — and Markle was the hippest of them all. Nonetheless, he and his bromance buds Burton, Coughtry and Rayner regularly recharged their creative batteries by spending time at a cabin on the Magnetawan River, near Georgian Bay.

Markle, who wrote an influential magazine profile of Gordon Lightfoot for Saturday Night, held intellectual court at the centre of a Toronto artistic coterie until he and his wife moved to Flesherton, where he lived and worked until his death in an auto accident in 1990. He was a robust sexual philanderer who painted nothing but nudes for most of his career, once declaring ‘My nudes are like Tom Thomson’s jack pines.’ I submit that Thomson’s jack pines are the equivalent of Markle’s nudes.

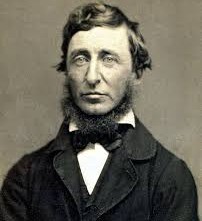

I’d now like to discuss Thomson, one of my favourite painters, in the context of one of my favourite writers, Henry David Thoreau. At first blush, you might not think of Thoreau as a rock star, but few American writers have been more influential on pop culture.

Moreover, in addition to Izaac Walton’s Compleat Angler, Walden was Thomson’s favourite book. I believe the painter and the writer were soulmates — definitely creatively and most likely philosophically.

Thomson took Thoreau’s words to heart, and put them into practice, when the latter famously confides: ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’

Thomson practiced the life of simplicity Thoreau outlines in Economy, the first chapter of Walden. Upon his death, Thomson had few personal possessions beyond his mandolin, painting equipment, fishing and camping gear — much of which went missing after his body was found floating in Canoe Lake.

Thoreau was not only important to Thomson, but was a significant influence on the Group, especially Lawren Harris (who became a follower of theosophy) and J.E.H. MacDonald (who named his son after the American Transcendentalist).

Transcendentalism was a movement encompassing literature, philosophy and spirituality, in addition to social and political concerns that developed in New England in the 1820s and ’30s in reaction to rationalism. It was very attractive to Thomson and the Group — as was the Arts & Crafts movement that emigrated from England to the Eastern U.S. in the latter part of the 19th century. Influenced by Romanticism, Platonism and Kantian philosophy, Transcendentalism posited that divinity pervades all nature and humanity. Its adherents, led by Thoreau’s mentor poet/essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, held progressive views on communal living and other aspects of living.

I’d like to outline some personal characteristics Thomson shares with Thoreau before touching on the symbol of the shack in the woods. The sympathetic link between Thomson and Thoreau is evocative. Here’s a few contact points:

- Both died young, Thomson a few weeks before his 40th birthday and Thoreau at 44. Moreover, Thoreau was born 100 years almost to the day (July 12, 1817) from when Thomson disappeared (July 8, 1917).

- Both ‘went away’ to take stock of their lives (Thomson to Algonquin Park and Thoreau to Walden Pond), which they subsequently documented and, in the process, created enduring art. As Thoreau once said, ‘I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.’

- Both embodied a sense of wildness expressed in and through their paintings and writings. The sense of wildness developed from intimate contact with nature.

- Both struggled in their own way with the defining political event of their time — Thomson with the First World War and Thoreau with slavery.Both struggled in their own way with the defining political event of their time — Thomson with the First World War and Thoreau with slavery.

- Both enjoyed fishing; the difference being that, whereas Thoreau came to question the practice of killing fish (it’s amazing that catch and release never occurred to him), Thomson never questioned the practice.

- Both were amateur musicians — Thomson played the mandolin as mentioned earlier; Thoreau played the flute.

- Both approached their art forms as diarists — Thomson’s small boards can be interpreted as journal entries in paint that he later worked up in the studio as completed canvases; likewise all of Thoreau’s writing, including Walden, Cape Cod, The Maine Woods and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, are built up from journals.

- Both are associated with the wilderness when, in fact, both lived in urban communities that were centres of arts and letters.

- Both experienced nature up-close and personal, creating art through attentive imaginative care to that immediate world.

- Both viewed themselves, and were viewed by others, as solitary artists, even though they maintained close associations with other writers or artists.

- Both were awkward connecting with people in a general, but valued close friendship. Both learned from teachers and both mentored others.

- Both reputedly maintained complicated relationships with women, which hasn’t discouraged commentators from questioning their implicit homoeroticism.

- Both are seen through the filter of time as radicals, marching to the beat of their own drummer. Thoreau’s manifesto Civil Disobedience influenced Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King and was the handbook for a generation of Civil Rights leaders. Thomson’s radicalism was more subtle and less political, but still influential as a challenge to the conventions of his day.

- In their respective national collective consciousnesses, both are connected for all time with specific places — Thomson’s Algonquin and Thoreau’s Walden, which are places of the imagination, of the heart, of the soul more than localities on a map.

Whether spending summers in a tent in Algonquin Park or winters in a studio shack in downtown Toronto (now located at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg), the connection between painter and setting in a Canadian context is comparable to Thoreau at Walden Pond in an American context.

British Columbia poet Harold Rhenisch, who titled his book of autobiographical, meditative essays Tom Thomson’s Shack, writes: ‘. . . Tom Thomson’s cabin is a door’ through which one walks into the landscape of his art. The same can be said of Thoreau’s famous cabin on the shore of Walden Pond, outside of Concord, Massachusettes.

The notion of a shack in the woods is a recurring metaphor/symbol in Canadian writing from Susanna Moodie’s Roughing It in the Woods and Life in the Clearing to Lawrence Scanlan’s Harvest of a Quiet Eye: The Cabin as Sanctuary, Monte Hummel’s Wintergreen: Reflections from Loon Lake, James Houston’s Hidaway: Life on the Queen Charlotte Islands, Larry Gaudet’s Safe Haven: The Possibility of Sanctuary in an Unsafe World, Hap Wilson’s The Cabin and John J. Rowland’s Cache Lake Country: Life in the North Woods — to name a few titles from my personal library.

As mentioned above, tracking Thomson’s influence on the history of contemporary Canadian visual art is a separate critical undertaking. However, the death of Ken Danby on a canoeing trip in Algonquin Park echoes Thomson’s death.

Danby didn’t start painting the North, where he was born and raised, until after his father died in 1994. With a longstanding interest in Thomson and the Group, he painted many images that recall or pay homage to the earlier painters. He painted Algonquin: Homage to Tom Thomson (Searching for Tom) in 1997; eerily, it became his own elegy.

He died of a heart attack in September 2007 in the arms Gillian, his wife, favourite subject and muse. ‘It’s as though Ken painted himself into his own picture,’ she told me during a chat in her late husband’s studio.

Tom Thomason as rock star would be incomplete without a public declaration of his celebrity status. So we have a bronze statue of the painter as anchor for a series of murals painted throughout the downtown heart of Huntsville. The picturesque Muskoka tourist town, located just south of Algonquin Park, lays claim to Thomson and the Group. The statue and public murals confirm the continuing interest in, and the widespread common appeal of, the painters, while raising issues of commodification and commercialization — regrettably a fate common to rock stars!

(featured image: Tom Thomson memorial cairn overlooking Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park)