Many go fishing all their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after.

— Henry David Thoreau

I’ve described myself as an armchair angler numerous times. I’m also an intrepid armchair traveler who gleefully circumnavigates the world through the pages of books, fascinated by picture and illustration as much as text and narrative.

Consequently, I fell for the Adirondacks long before dipping the toe of one of my wading boots into the cool, clear waters of the state park, which spans much of the northeastern corner of upstate New York. My introduction to the largest park in the contiguous United States was through its conservation ethic, history, literature, architecture, art and rustic crafts — not to mention fly fishing.

For my money Bill McKibben’s memoir Wandering Home is the perfect introduction to the Adirondacks. Subtitled A Long Walk Across America’s Most Hopeful Landscape, it chronicles a hike he made from his new home in the Robert Frost Country of Vermont through the Adirondacks, where he lived for many years. As we accompany him on his inspiring trek through a beautiful landscape, we meet a cast of engaging characters including eco-activists, organic farmers, vintners, beekeepers and fellow writers.

Ditto for Russell Banks’ Adirondack novels including Affliction, The Sweet Hereafter (adapted into a tender film in 1997 by Canadian Atom Agoyan, starring Ian Holm and Sarah Polley), Cloudsplitter (about John Brown who lies buried at his farm outside Lake Placid) and The Reserve. Some of the stories in The Angels on the Road and A Permanent Member of the Family are also set in the region. Banks continues to divide his time between Keene, south of Lake Placid, and Miami. I contend his Adirondack fiction is his best.

With respect to fly fishing in the Adirondacks, an angler can do no better than Fishing the Adirondacks, by the legendary Fran Betters, in addition to Good Fishing in the Adirondacks, edited by Dennis April (which includes an essay on the West Branch of the Ausable River by Betters) and Fishing the Adirondacks: A Complete Angler’s Guide to the Adirondack Park and Northern New York, by Spider Rybaak.

In the 19th century the Adirondacks acted as a magnet drawing artists to its scenic splendour, wilderness romance and fresh air (before the arrival of Acid Rain which is sure to increase again with fossil fuel fanatic Donald Trump taking up space in the White House). The list is too long to delineate, but begins in the 1830s with Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, John William Hill and Charles Cromwell Ingham, four of the period’s most prominent artists.

By mid-century the area became a northern extension of the well-known Hudson River School, attracting such artists as John Frederick Kensett, William Trost Richards, Sanford Gifford and Homer Dodge Martin.

In the 20th century John Marin and George Grosz gave visual expression to the area.

In my view, there are no better visual guides/companions to the Adirondacks than Winslow Homer, the great 19th century painter who needs no introduction, and Rockwell Kent, in my opinion America’s most undervalued 20th century artist.

I highly recommend David Tatham’s Winslow Homer in the Adirondacks and Winslow Homer: Artist and Angler. Among his many artistic accomplishments, Homer remains America’s most accomplished outdoors painter who transformed picturesque genre pictures into enduring art.

Tatham’s premise — with which I concur — is that Homer’s Adirondack oils and watercolours comprise an original investigation into humanity’s relationship with the natural world at a time when established preconceptions about humans, nature and art itself were undergoing significant change.

With essays by Tatham and renown angling historian Paul Schullery, former executive director of the American Museum of Fly Fishing, among others, Artist and Angler surveys Homer’s angling oeuvre encompassing the Adirondacks, Maine, Florida and Quebec. I believe the Adirondacks cut the deepest impression.

Although Kent painted landscapes spanning such far-flung places as Newfoundland, Alaska, Maine and Greenland, even Tierra del Fuego, his love of the Adirondacks ran pure and deep. His intense affection for the area illumines The View from Asgaard: Rockwell Kent’s Adirondack Legacy, by Caroline M. Welsh and Scott R. Ferris.

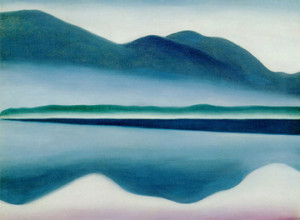

A giant of modern art has a connection to the Adirondacks that is overshadowed by her celebrated association with the landscape of the American Southwest.

A young Georgia O’Keeffe vacationed with her photographer husband Alfred Stieglitz on Lake George, where Stieglitz’s family owned an estate, before she heeded the call of the dramatic forms and intense light of the New Mexico desert. (She once confided she would have immigrated to Canada were it not so cold.)

Now let’s move on from printed word and image to personal experience. When I recently visited the Adirondacks for five days of fly fishing on the famous West Branch, between Lake Placid and Wilmington, I was reduced to a quivering, love-sick pup. I was so smitten I’m still blushing as I pound away days afterwards with four fingers on the computer keyboard.

Because this is a blog rather than a tourism column, I’m going to offer my highly subjective impressions and observations based on the all-too-short period I was there. It goes without saying, I can’t wait to return.

The highlight of my most fulfilling eventide of fishing in early June was landing a 15-inch brown trout — a personal best — minutes after catching an eight-incher. I caught them at the top of the pool above Monument Falls, with an Ausable Caddis, a pattern designed by Betters, who covered all the angling bases as angler, fly designer and tier, vintage bamboo rod and reel collector, writer and fly shop owner. He’s most responsible for putting the West Branch on the fly fishing map — at least in the modern era.

The heartbreak — and there’s always an element of heartbreak with fly fishing — came with my camera’s forsaking me. The result: I have no photographic record of the momentous event. Adding salt to the piscatorial wound, I had taken photos earlier in the day; however, I failed to check whether they had turned out. They didn’t. Had I done my due diligence, I would have made the necessary menu adjustments before hitting the Falls. Talk about a fly fishing fool.

Now I face the cruel reality of living without a photo to offer cosy comfort on the long, dark winter nights of my approaching dotage. On the brighter side, I suspect that over time the length of the mighty leviathan will grow substantially in my memory archive.

The snafu was compounded by Dan — my fly fishing buddy and a fine photographer — not having his Nikon digital camera, which is as much a component of his gear as rod, reel and waders. He mistakenly left his charger at home, so was forced to use his camera sparingly. We were both surprised that there are no camera stores in the immediate area.

It’s drag on a long dead drift when the mischievous Mr. Murphy — you know, the Murphy’s Law dude — shows up on a trout stream, which happens frequently enough to keep things from stagnating.

When I described my fish tale of woe to my long-serving angling buddy Gary, who I’ve known since our Trent University days 45 years ago, he commiserated sympathetically: ‘Why do our cameras screw up on our one big fish and capture every embarrassing thing we do in life?’ Why indeed.

Fortunately, Dan had a tape to measure the fish after he and his brother, Martin, witnessed the landing. The whole mess proved ironic because one of the things I most enjoy about fly fishing is its elegant, low-tech aesthetic. The simpler things are, the less chance of something going south — or so the theory goes.

Whether viewed as a small river or a large stream, the West Branch is a lovely fishery meandering 58 kilometres (36 miles) — much of it at the foot of majestic Whiteface Mountain. It boasts abundant browns and occasional rainbows, in addition to native brookies in its headwaters and smaller, colder tributaries. There’s lots of diverse water to accommodate the concentration of anglers it attracts, featuring long runs and deep pools, placid stretches and anxious pocket water — all holding fish. There are two catch & release zones totalling 11.6 kilometres (7.2 miles).

Access is easy because much of its primo water runs adjacent to Route 86 and River Road, which explains why a goodly percentage of anglers I saw revealed tufts of grey hair beneath their ball caps and oilcloth hats. I saw more anglers using wading staffs than anywhere else I’ve fished in the last decade.

The abundant hatches of caddis, mayflies and stoneflies follow closely the timing of the hatches on the Grand River, my homewater in southwestern Ontario; perhaps a tad later because of the more northern latitude and higher elevation.

I wanted to cast famous patterns designed by Betters. In addition to his Ausable Caddis, I used his Haystack — I’ll leave it to angling historians to debate whether it’s the precursor to the comparadun or whether the comparadun is really a haystack — Ausable Wulff and Ausable Bomber. I also purchased a half dozen of his Usuals for the Grand, where the pattern proves effective.

I was impressed with the two fly shops in Wilmington. They seem to thumb their noses at aggressive competition in favour of courteous co-existence. Smart business, really.

When I went to the fly shop at the Hungry Trout Resort in search of the Ugly, a local pattern made of raccoon, coyote and muskrat fur, I was informed that the fly shop down the highway retained exclusive distribution rights. Moreover, the clerk praised the woolly bugger-style fly as nothing short of deadly.

Incidentally, this is the only place you can pick up a copy of Betters’ Fishing the Adirondacks for the bargain price of 10 bucks.

Our one and only gourmet dinner was enjoyed at the resort’s handsome restaurant festooned with rustic angling and hunting objects d’art and memorabilia. Martin and I dug into the Guide’s Platter, featuring lightly pan-fried trout, medium-rare venison chop and roasted quail, accompanied by a medley of interesting vegetables. Cooked to perfection and delightfully delicious.

Similarly, the Ausable River Two Fly Shop, which carries Betters’ fly patterns masterfully replicated by area tier John Ruff in addition to the Ugly, was equally pleasurable. On my initial visit Rarilee, a natural charmer, gave me the rundown on Betters’ flies. She also offered to point out sections of the river that had been especially productive in recent days.

However, before we discussed the honey spots, I got irreversibly sidetracked. I mentioned I was interested in Homer and Kent and she told me Asgaard Farm, where the latter lived for half a century, was a mere 10-minute drive away.

When I returned the next day, her husband John made time to transcribe directions from the farm website. Turns out, he had done some work at the dairy farm a few years previously.

The pair of fly shops reflected the friendliness I encountered throughout the Park. The clerk in a liquor store in nearby Saranc directed me to the last bottle of Maker’s 46, a fine Kentucky bourbon at a ridiculously discounted price, before telling me where I could purchase a New York State fishing licence.

Similarly, Lori, the courteous clerk at Lake Placid’s Bookstore Plus, went out of her way to ensure I found the book I was seeking. She then paged the store’s resident fine art specialist who informed me about the Rockwell Kent Gallery and Collection of the Plattsburgh State Art Museum at the State University of New York, which houses the most complete and balanced collection of Kent’s work in the U.S.

The gallery will be a primary destination on my next visit, as will the Adirondack Experience (formerly the Adirondack Museum) in Blue Mountain Lake.

Carol, owner of Spruce Lodge B&B, where I stayed in Lake Placid, threw down the welcome mat. She knows the area like the back of her hand; any question I asked that stumped her, she made sure she found the answer. The Lodge offered Hospitality Plus.

Henry David Thoreau is not the only writer to affirm that angling is about more than catching fish. I think this is especially true with fly anglers. I never go on a fishing adventure without prospecting its arts and cultural waters. And I’m not the only angler to do so.

Dan, Martin and I made a couple of enjoyable side trips — to the aforementioned Asgaard Farm, outside of Ausable Forks, and to the Museum of American Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont, where we also visited the Orvis mothership retail outlet, conveniently located next door.

We took a lovely, three-hour scenic route on Hwy 9N through such historic places as Ticonderoga to the museum and outdoors retailer. We made it back in just over two hours on Interstate 86, which is quite lovely in its own right.

Now to Rockwell Kent. Asgaard is a bustling dairy operation spread over 200 acres. When I asked a lady working there if this was the farm where Kent (1882-1971) lived, she acknowledged it was and told us we could check out his studio, nestled in the woods at the edge of a ridge. ‘Feel free to look around,’ she offered. ‘It’s unlocked.’

The handsome brown studio with cedar shakes on the roof is in need of caring restoration, but walking around freely was a wonderful experience, like a precious gift. I could feel the ghostly presence of the artist, making for a disarmingly pleasant sensation.

There were some photos of Kent, a drawing of the layout of the farmhouse on a drafting table, a divan, some chairs presumably rescued from a schoolhouse and racks to hold incomplete canvases and finished pictures, in addition to some tools in a woodworking shop where picture frames were constructed.

I’m not sure whether the paint brushes and knives, palettes and other paraphernalia actually belonged to the artist or were period objects placed there to create atmosphere. If they did belong to the artist, it’s an acknowledgement of respect that they have not been stolen. An altogether remarkable experience, one unlike any I’ve ever enjoyed.

Other than my fascination with the Adirondacks, my interest in Kent — an unjustly neglected artist in his own country because of his blend of thorny Yankee independence (he was a New England Transcendentalist in the tradition of Emerson and Thoreau) and communist sympathies (he gifted a significant amount of his art to Russia in response to neglect in his own country because of his politics) — was spurred by his influence on Lawren Harris (1885-1970), a founding member of the Group of Seven.

While the critical chill towards Kent — who was also an architect, printmaker, commercial artist, book illustrator, muralist and designer of jewellery, textiles and pottery, as well as published author — has thawed since the Cold War, a comprehensive reappraisal is long overdue.

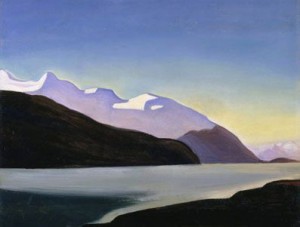

A comparison of Kent’s paintings from 1917 through 1920 with Harris’ late 1920s-1930s paintings of Lake Superior, Rocky Mountains and Far North confirms a striking creative sympathy between the two artists. It’s easy to mistake the works of one for the works of the other; they are so remarkably alike.

Although they painted in response to particular terrains, both artists were fuelled by a spiritual drive (not ignited by institutionalized religion) that embodied an inner soulscape as much as it reflected external landscapes. You feel the sublime, inner power of nature in the work of both artists, featuring highly stylized, sculptural forms and deep, penetrating colours that reduce Nature to its elemental essence. I’m reminded of English visionary poet William Blake’s assertion: ‘For every thing that lives is Holy.’

In Inward Journey: The Life of Lawren Harris, biographer James King confirms that Harris owned a suite of photographs of Kent’s work. Harris seems to have been familiar with the work of his contemporary in the 1920s. They might well have met in the Rockies around 1924, King speculates. Nonetheless, a friend of Harris’ visited Kent’s studio in the early 1920s and recognized how much the artists shared in common.

In Four Decades: The Canadian Group of Painters and Their Contemporaries, art historian Paul Duval confirms that Harris’ interest in the Arctic in the 1930s reflected Kent’s earlier paintings of Alaska and Greenland. Harris and Kent met in the 1920s when the American was invited by the Art Gallery of Toronto to lecture, Duval reports. Apparently they became close friends. Kent was a frequent guest of Harris’. He visited the Studio Building, where a number of the Group of Seven had studios, as well as Harris’ home.

Clearly the artists were creative soulmates who transformed personal spiritual impulses into enduring art — at a time, by the way, when landscape was rejected as conservative and dismissed as irrelevant by the fashion-conscious cognoscenti.

POSTSCRIPT 1: Harris and his wife Bess spent a couple of years in the early 30s in Hanover, New Hampshire, a historic town in the Upper Connecticut River Valley on the border of Vermont. The landscape would have been comparable in many ways to Kent’s Adirondacks. The couple then relocated to O’Keeffe’s New Mexico before moving back to Canada and living out their days in Vancouver, along with fellow Group of Seven founding member Fred Varley.

POSTSCRIPT 2: An interesting thought occurred to me earlier this spring while viewing the major Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario. I wondered if she had been influenced by Kent. Look and compare one of her landscapes to Kent’s and decide for yourself.

Lake George (formerly Reflections Seascape – 1922) by Georgia O’Keeffe. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

FOOTNOTE: Acclaimed Newfoundland author Michael Winter wrote The Big Why, a compelling novel published in 2004, that imagines a year in Kent’s life. At the age of 30 in 1914, Kent forsakes the superficial world of New York City for the isolation of Brigus, Nfld, with plans for his wife and three children to follow later. He’s drawn to The Rock by a fascination with the raw and rugged Atlantic coast and by Brigus’ celebrity resident, Arctic explorer Robert Bartlett. Once in Newfoundland, however, Kent discovers that notoriety comes easier in a small town than in The Big Apple. As dark war clouds move in, Kent becomes a polarizing figure in the enclosed, impoverished community, where everyone knows everyone else and outsiders are suspect.