Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout these days of mystery devoted to the painter’s life, art and legacy. The last of nine instalments, Casting on a Northern River, guides readers through one of Thomson’s great paintings. Long may he live in the hearts, minds and souls of Canadians.

Where the long river flows

It flows by my window

Where the tall timber grows

It grows ’round my door

Where the mountains meet the sky

And the white clouds fly

Where the long river flows

By my window….

— Gordon Lightfoot

… Oh I wish I had a river, I could skate away on….

— Joni Mitchell

Hope and the future for me are not in lawns and cultivated fields, not in towns and cities, but in the impervious and quaking swamps.

— Henry David Thoreau

… imperfect notes destroy the soul of music, so does imperfect colour destroy the soul of the canvas….

— words attributed to Tom Thomson in a 1930 letter from Ranger Mark Robinson to biographer Blodwen Davies

The standard critical assessment of Tom Thomson’s pictures is that his small boards painted plein air in Algonquin Park are superior to the canvasses worked up and completed in the studio over winters in Toronto. While I don’t necessarily disagree with the evaluation, it’s skewed for the simple reason that so few large canvases are represented in his oeuvre. Premature death made sure of that.

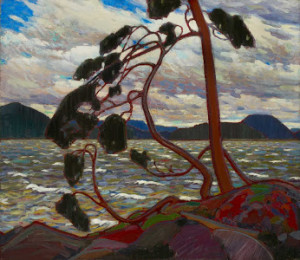

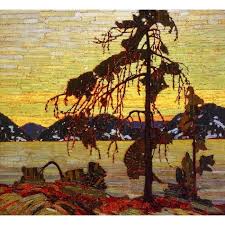

The West Wind remains regrettably incomplete. However, Northern River and The Jack Pine are undeniably great paintings, masterworks by any standard or definition; forever standing strong and true at the apex of Thomson’s achievement, despite the foul, fickle winds of taste and fashion.

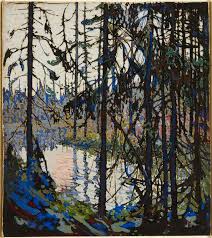

A great painting opens a unique window onto an artist. I’d like readers to accompany me as I cast my fly/eye over Northern River. Along with The Jack Pine, it’s not only my favourite Thomson painting; it’s one of my favourite paintings in the long history of art. It’s a painting I adore; a painting I love.

If Northern River is not a great painting, then everything I’ve said in previous blog postings is hokum or bunkum, call it what you will. If you have read them, you have wasted your time if you don’t acknowledge the greatness of Northern River. For everything I’ve said leads to Northern River, the pictorial compass by which we find the True North of Tom Thomson.

Its title is significant. Like The West Wind and The Jack Pine, Northern River does not reference a specific place or particular location. Rather, it’s a generalized, unidentified place, representative and emblematic of all northern rivers (whatever the term ‘northern’ means to you). Moreover, it embodies and reflects an Idea of North, irrespective of what the painter intended. Great art transcends intention; it’s all about execution, the thing that really matters.

The painting reminds us that North is not only a direction on the compass, a geographical location, a geological formation or a degree of latitude. North is also an idea — an intellectual, emotional, psychological and spiritual construct.

The painting’s title welcomes us to ‘enter’ the picture; it invites us to ‘read’ the picture, metaphorically and symbolically as well as literally. I’m reminded of Robert Frost’s The Pasture:

I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away

(And wait to watch the water clear, I may):

I sha’n’t be gone long.—You come too.

I’m going out to fetch the little calf

That’s standing by the mother. It’s so young,

It totters when she licks it with her tongue.

I sha’n’t be gone long.—You come too.

The painting starts out as a representational depiction of nature. It’s almost photographic. Thomson was obsessed with getting it right in terms of line, colour, texture, dynamic of light and shadow. In these formal elements lie atmosphere and mood. But all great poems and pictures that depict external nature through words and imagery simultaneously portray inner states of being (mindscapes, emotionscapes and soulscapes) — what Frost refers to in Tree at My Window as ‘inner weather.’ Here are the last two stanzas:

But tree, I have seen you taken and tossed,

And if you have seen me when I slept,

You have seen me when I was taken and swept

And all but lost.

That day she put our heads together,

Fate had her imagination about her,

Your head so much concerned with outer,

Mine with inner, weather.

Northern River presents a view canoeists and anglers recognize immediately. It’s as if we are portaging from one waterway to another or anxiously approaching a riffle, run or pool around the next bend. I’ve experienced this many times with fly rod in hand.

The picture establishes an intimate relationship between viewer and the natural world. This is nature up-close and personal. We’re not observers looking at nature from a distance — whether panorama from a hill top or vista of shoreline from a canoe. Instead, we are participants immersed in, and enclosed by, nature. We are embraced in nature’s arms

The picture conveys a sense of tactile, sensory stimulation. We feel our hiking or wading boots sinking in the soft forest floor of decaying leaves and pine needles; we smell the moistness of the flora shielded from harsh sunlight by overhanging branches; we hear the sounds of insects, birds, frogs, maybe even animals. We swat at mosquitoes, black flies, deer flies and the blood-sucking midges known as no-see-ums as we grab for insect repellent laced with DEET.

Northern River is not conventionally attractive. It lacks the majestic splendour of white pine or jack pine prominent in the other masterworks. These are spruce or tamarack; low-grade swampland trees lacking distinctive sculptural form.

A number of commentators have observed that the ornamental lacework of the foreground trees resembles stained glass windows. To my eye, they suggest Art Nouveau ironwork or tiffany lamp shades. It’s a pictorial strategy Thomson returned to frequently in such pictures as In the Northland, Autumn’s Garland, White Birch Grove, Snow in October, Early Spring, Autumn Birches, Northern Landscape, Opulent October, Forest, October and Algonquin Park, among others.

However, I don’t discount the association with church or cathedral. I haven’t read much with respect to Thomson’s religious beliefs — or lack thereof. Personally, I don’t see him as either a denominational adherent or regular churchgoer in any conventional sense. But I do believe he painted nature with a spiritual brush.

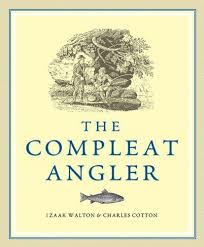

I believe he considered the ‘wilderness’ of Algonquin Park sacred, comparable to when English visionary poet William Blake declared that, ‘Every thing that lives is Holy.’ This is supported by a couple of favourite books he kept close at hand: Izaac Walton’s Compleat Angler and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. In different ways, both books reflect a spiritual attitude toward life. He also would have heard about New England Transcendentalism from his artist companions. More significantly, close study of Thomson’s paintings lead inconvertibly to the same conclusion. So, stained glass it is.

It’s also the reason I reject any suggestion that Thomson committed suicide. I’m not a psychiatrist, but I believe that, had the painter ever become despondent enough to take his own life, it would not be in the place he loved most.

It’s commonplace for people to assert that Vincent van Gogh, that beautifully tortured soul, was mad when he cut off his ear. But read his clear, lucid letters to his brother Theo and you get a picture of a deeply sensitive, yet sane, artist. Similarly, look closely over the boards Thomson painted during his last spring and tell me, truthfully, they reveal an artist losing a battle to despair. The pictures tell a different story.

Northern River records a transitional time, as darkness of night gives way to light at the dawning of a new day. The foreground trees mark a threshold from dark to light, terrestrial to aquatic and aerial. We are led from the darkness of the bush to the light of sky reflected and refracted by water. I think of Thoreau looking into the eye (or I) of Walden Pond.

The passage from darkness to light, at once literal and metaphorical, also reminds me of a couple of titles of Ernest Hemingway stories: A Clean, Well-Lighted Place and The Last Good Place. Moreover, in setting and mood, Northern River brings to mind my favourite Hemingway story — Big Two-Hearted River.

Nick Adams is a damaged young man who is back from the devastating wasteland of WWI Europe. He’s returned to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, a place the knows well — which, incidentally, resembles in some places Algonquin Park. Although ostensibly on a solo fishing trip with fly rod and camping gear in hand, Nick is actually seeking regeneration and redemption — water being symbolic of restoration and renewal, healing and baptism.

I would like to conclude casting on Northern River with some thoughts about the great Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye, who wrote about Thomson and the Group of Seven. But before getting to Frye, I’d like to consider the painting in terms of the picturesque, the beautiful and the sublime, a trio of aesthetic concepts derived from philosophy that developed over the 18th and 19th centuries. They not only came to define landscape painting but became classifications of the natural world as expressed through literature as well as art.

I contend Northern River is a masterful blend of all three aesthetic concepts.

The picturesque, which refers to the charm of discovering landscape in its natural state, is implied by the perspective of the viewer as surrogate canoeist or angler. This is the source of the picture’s serene, peaceful, meditative mood.

The beautiful — which traditionally referred to humanity’s taming of, or dominion over, nature and which I interpret as relationship between humanity and nature — is represented by the river which is emblematic of human existence as a journey along the time-space continuum. This encompasses the cycle of life, with its vagaries of mutability and mortality.

The sublime, with its elements of awe and reverence, is represented by the sky as a metaphor of infinity and eternity. Traditionally the sublime provoked a sense of terror in the face of nature at its most dangerous and fearsome, which doesn’t apply here. This is the source of spiritual optimism the picture affirms by imposing a sense of design on the chaos of nature.

In a final touch, the river of historical time is connected to timelessness by the reflecting and refracting sky; hence we have an intimation of the eternal embodied an enacted in the temporal.

I don’t know whether Frye is read much these days. I doubt it. But when I studied literature at university in the 1970s he was a giant, as influential a critic as there was anywhere in the world. And he was ours.

One of his most famously contentious notions, at least in terms of Canadian literature, was the garrison mentality wherein characters in response to ‘deep terror in regard to nature’ look outwards after constructing metaphorical walls against a hostile outside world. Frye argued that this mentality, which was integral to Canadian identity, was caused by fear of the emptiness of the landscape, in addition to the oppressiveness of other nations, especially the U.S.

Canadian writer Robertson Davies recognized a similar strain in the Canadian character, but expressed it in Jungian terms as Canadian introversion and American extroversion.

Margaret Atwood, who took classes from Frye while an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, subsequently explored the notion of the garrison mentality in her landmark study Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. Her mentor returned the favour by calling his 1971 collection of essays on the Canadian imagination The Bush Garden. Atwood had called the first dream poem in her 1970 poetry collection The Journals of Susanna Moodie by the same title.

I mention all of this here, not as a digression, but as a way into Northern River, which I interpret as a rebuttal of the garrison mentality, with its accompanying sense of alienation and loneliness against a hostile universe.

Instead, Northern River is the pictorial embodiment of the Bush Garden — a garden in the Canadian wilderness.