Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout those days of mystery devoted to aspects of the painter’s life, art and legacy. The fourth instalment, Epistles from the Grave, is built around a couple of letters that shed light on events surrounding the painter’s death. As such, it’s a modest contribution of primary source material to the Tom Thomson story.

One of the most exciting things that ever happened to me as a newspaper reporter for nearly four decades occurred in January 2011. I had written a story as an arts writer with the Waterloo Region Record on Tom Thomson in advance of an exhibition, Searching for Tom — Tom Thomson: Man, Myth and Masterworks, scheduled to open at THEMUSEUM in downtown Kitchener.

I enjoyed writing the story because Thomson is one of my favourite Canadian artists. I have viewed his work in various galleries many times and read almost all of the books about him. I have visited and camped in Algonquin Park numerous times since childhood. I have paddled Canoe Lake and visited the Mowat Cemetery where some believe Thomson is buried. Moreover, as a professional journalist I have written about his art multiple times. I also share with the painter a passion for fishing.

In response to the story, I received a telephone call from a Kitchener man who, as it turned out, lived around the corner from me and my family in the established neibourhood of Forest Hill. He said he had a couple of letters he had kept for four decades that might be of interest to me. We agreed to meet. This is the story about the letters and their consequences.

The letters written in the 1970s connected the longtime Kitchener resident to the mystery of the legendary Canadian painter. Moreover, the correspondence provided tantalizing tidbits about the circumstances surrounding the painter’s suspicious death in 1917, at the age of 39.

Darcy Spencer was a scoutmaster in 1960 when he started taking scouts from the 26th Kitchener Troop on annual canoe trips to Algonquin Park. When I first met him early in 2011 he was sitting in his family room amid posters of paintings by Thomson and photographs of Algonquin Park. Spread out in front of him on a small table was a map of the provincial park that detailed where he canoed not only with scouts, but subsequently with his children and grandchildren every year until two years previously.

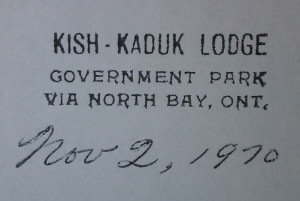

In the 1960s Spencer arranged for canoes and supplies through Jack Wilkinson, who operated Kish-Kaduk Lodge on Cedar Lake with his cousin Rose Thomas. After operating the business for 49 years, they sold out to the provincial government in 1976, with the provision they be allowed to live in a house on the property.

Spencer and Wilkinson not only became good friends, they shared a mutual interest in one of Canada’s most famous — or infamous — artists. ‘I got to know and appreciate Jack,’ Spencer recalled, describing his friend as ‘a prince of a man. He was a man of integrity, as honest as the day is long.’

Wilkinson and his cousin knew Thomson, who visited Algonquin Park annually from 1912 through 1917, when he died under perplexing circumstances at Canoe Lake. Wilkinson was six years old at the time.

Although the coroner’s report cites death by drowning, the cause of Thomson’s demise remains unresolved — or rather unsolved, if you prefer. There are questions of whether it was by (1) natural causes (a heart attack or stroke), (2) accident (falling out of the canoe while relieving himself), (3) suicide (some believe he was manic-depressive or bipolar), (4) manslaughter (resulting from a drunken fist fight) or (5) premeditated murder (various motives and suspects have been identified).

In a letter written to Spencer on Nov. 2, 1970, Wilkinson states he was annoyed by what he claimed were inaccuracies in books about Thomson, specifically William T. Little’s The Tom Thomson Mystery which was published that year, and in a CBC-TV program. Although he doesn’t identify the show, he’s referring either to the documentary Was Tom Thomson Murdered? based on Little’s book, or an appearance Little made on Oct. 19, 1970 on Front Page Challenge, the popular newsmagazine quiz show that aired from 1957 through 1995.

‘He was reluctant to talk about the incidents of 1917,’ Spencer said of his friend. ‘The only reason he wrote the letter was to correct inaccuracies.’ Wilkinson didn’t provide more information than required to set the record straight. ‘He didn’t go beyond what he thought people needed to know.’

‘The CBC program and the books now out about Tom Thompson (sic) are causing an awful lot of controversy,’ Wilkinson writes. ‘It is most unfortunate’ that almost all of the adults who knew Thomson were dead, ‘and all (who) are left are us younger fry.’

Wilkinson, who was 59 in 1970, recalls meeting Thomson when he was a child. Although Thomson was admired by some people in the park, including chief ranger Mark Robinson, others shared Wilkinson’s dislike of the painter.

The negative opinion of Thomson is obscured by caretakers of the painter’s iconic legacy. However, it’s confirmed in Roy MacGregor’s Northern Light, a book published in 2010. Subtitled The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him, it advanced new information on the painter, including how he was viewed by others who lived and worked in Algonquin Park. McGregor, a prominent Canadian journalist and author of numerous books including Shorelines (later published as Canoe Lake with a new prologue), A Life in the Bush, Escape, The Weekender and Canoe Country, maintains close family ties to the park and to some of the people who became associated with the painter.

‘I … saw him and spoke to him often, but in my childish way, did not like the man,’ Wilkinson writes. ‘When I said, ‘Good Morning, Mr. Thompson’ (sic) or ‘Good Day, Mr. Thompson,’ (sic) he would usually ignore me. His mind was away off somewhere else.’

Although Thomson spent time as a ranger and guide when he wasn’t fishing, he was viewed as an aloof, self-absorbed bohemian by working-class locals understandably unfamiliar with, and suspicious of, the artistic life. ‘I can see him to this day … He was always grubby looking. Wore a felt hat at all times, his shirt with the sleeves down around his wrists on the hottest day, an old pair of pants and shoe packs (a type of high moccasin worn in the bush),’ he writes.

Wilkinson remembers seeing Thomson for the last time. He and his cousin were at Canoe Lake Station, where his ‘Auntie’ (Thomas’ mother) was station mistress. ‘We saw him the same morning as his canoe was found in the afternoon. He was up to the station with Shan(non) Fraser (operator of Mowat Lodge, where Thomson often stayed) for something, and both he and Shan were talking to Auntie, and Rose and I stood by listening to the conversation,’ he writes.

Wilkinson then drops a deliciously intriguing hint of something sinister — details of which accompanied him to the grave. He implies he’s willing to tell Spencer what he knows about Thomson’s death. ‘The next time I see you we can tell you about the drowning.’

Unfortunately and regrettably, the two friends never discussed the matter further. Wilkinson would have had memories and recollections from personal experience in 1917.

He also would have been privy to discussions that most assuredly would have taken place among the locals over the years following Thomson’s death as the painter passed from man and artist to legend and myth and, in the process became a symbol of the Canadian wilderness — The Mystic North — so deeply ingrained in this country’s psyche and soul.

This suggests the residents of Canoe Lake knew more about the circumstances surrounding Thomson’s death than they ever revealed. In other words, a conspiracy of silence was agreed upon by a small, close-knit, insular community.

Like a fishing lure hitting the water, the mystery of Tom Thomson is defined by expanding circles of conspiratorial silence, encompassing (1) the Canoe Lake community, (2) the painters who formed the Group of Seven three years after Thomson’s death, (3) Thomson’s patron James MacCallum and (4) Thomson’s family. All had reasons to protect the painter’s reputation and legacy, even if it meant concealing the truth or, at the very least, obscuring what they knew.

Wilkinson goes on to discuss the recovery of Thomson’s body. He talks about the copper trolling line that was wrapped around Thomson’s left leg, which is important because the fishing line was generally thought to provide evidence of foul play.

The fishing line triggered speculation that it was attached to something heavy to weigh the body down after being disposed. This was thought to explain why it took so long for the body to float to the surface of a warm, shallow lake.

Moreover, there were conflicting accounts of who actually discovered Thomson’s body.

‘The CBC has it all mixed up,’ Wilkinson writes. ‘It was Dr. (Goldwin) Howland who found him alright (sic), but it was Dr. Howland’s little girl who caught him on her fishing line, while Doc had her out fishing in a row boat.

‘The fishing line that was wrapped around (Thomson). Old Doc put there. He wrapped his daughter’s trolling line around the body, towed it to shore, and fastened it to a stump so it could not float away, and then went up to the house and got a piece of canvas and threw over the body. When you find a body in the water, it is against the law to take it out, so you fasten it to the shore so that it cannot float away until the coroner comes along, then you take it out for an autopsy, and that is exactly what Doc Howland did.

‘I doubt to this day that the Howland girl knows she hooked up Thompson (sic). She was not told at the time, because as soon as the Doc saw the body come up a way back behind the boat he broke the girl’s line, rowed her to shore and sent her up to the cottage, while he went back and towed the body in to shore, wrapped the cut line around it and tied it to a stump. So there was no mystery about the line wrapped around him.’

Ross King in his excellent 2010 study Defiant Spirits: the Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven advances a comparable explanation.

Although accounts of Thomson’s death and recovery mention Howland, Wilkinson says there were two other doctors on Canoe Lake — T.A. Bertram and A.J. Pirie. Both are mentioned in Audrey Saunders’ Algonquin Story, originally published in 1946. ‘They only mention Dr. Howland. They all had cottages there.’

Then Wilkinson refers to a woman, ‘Mrs. Kennard,’ who was living in Florida in 1970. ‘(She) is the only adult left who knew Thompson (sic). She knew him as well as anyone, and she and her husband used to feed him.

‘She was a lousy cook, but Tom Thompson (sic) was an excellent cook, so our old friend … and her husband used to buy the food and Tom would cook the dinner and they all ate together.’ This confirms Thomson’s culinary skills, which were reported in earlier biographical accounts. It also reveals the painter’s sociable side, a contrast to his image as a taciturn loner.

Wilkinson and Thomas were the only children in the park during the time Thomson spent there, with the exception of the Frasers’ daughter, Mildred. In 1970, they were the oldest residents in the park, having lived there 57 years. ‘It makes one feel ancient, ” Wilkinson concludes.

He ends his letter with a provocative invitation. ‘Sometime when you are up and have an hour, we will talk your ears off if you are interested.’ However, Spencer never took his friend up on the offer. ‘I never asked Jack about Tom Thomson out of respect for Jack.’

The correspondence between two old friends, who shared both a love of wilderness and a mutual respect for one another, tantalizingly reflects so much of the mystery that haunts the painter made notorious by questions we can never answer. Nothing fuels legend more than rumour, innuendo and gossip, not to mention conjecture, speculation and accusation.

Interestingly, there’s no reference in the letter to the controversy surrounding Thomson’s final resting place — either in the family plot at Leith (near Owen Sound), where he was raised; or in an unmarked grave a short distance inland from Canoe Lake, where MacGregor argues — quite convincingly in my opinion — the body is buried.

Wilkinson refers to Thomson in one other letter, typewritten and dated Aug. 17, 1976. It refers to Thomson’s sociability again, including his fondness for alcohol and female company. In Northern Light MacGregor contends Thomson’s attraction to women caused resentment among the men in the park. Some suggest it might have been is undoing.

The passage in the letter contains racial stereotypes that are offensive by today’s standards but which, unfortunately, were commonplace at the time the letter was written. (I fear these prejudices are still very much with us based on evidence reported regularly on CBC National News and elsewhere.)

‘Regarding the Indian farm where Tom Thompson (sic) used to spend some time at hoochy kootchie (sic). It is already marked as an historical site ….

‘One slight correction, Thompson (sic) did not spend his winters there, but part of his summer time there, with winters in Toronto. When he wanted to do the ‘rain dance’ he used to beat it up to the old Indian Farm where Ignace and Mabel Dufond had a cute, little niece of ‘dancing age’ and that is where he danced the hootchie kootchie (sic).’

In Algonquin Story Saunders describes the Dufonds as one of the park’s pioneer families who gave ‘rise to many tales’ and reflected ‘the spirit of the times,’ including consumption of illegal alcohol.

‘Old Pete Ranger the park ranger of those days used to tell me that after the joy juice was gone and all heads back to normal they used to kick him out until he would arrive back at a later date for another party, ” Wilkinson writes. ‘Hell of a way to write about a celebrated Canadian, but there was a little Indian in everyone in those days.’

Whatever he means by ‘rain dance’ and ‘hootchie kootchie’ — the latter refers to a sexually provocative dance popular at the turn of the last century — the portrait of Thomson is not flattering, laced with titillating sexual innuendo. It challenges the romanticized portrait painted by the Group of Seven and others of ‘a heroic woodsman-artist of the north,’ as described by Sherrill Grace in Inventing Tom Thomson. Rather, the depiction of Thomson is closer to the man portrayed by MacGregor, as well as David Silcox in Tom Thomson: The Silence and the Storm.

Similarly, it complicates his relationship with Winnifred Trainor, believed by some biographers to have been Thomson’s fiancée. MacGregor contends in Northern Light that his distant relative might well have been pregnant with the painter’s child.

Over the years ‘Jack mentioned a few things about Tom Thomson but nothing related to the incidents of 1917,’ Spencer acknowledged when we talked. He remembered suggesting that Wilkinson appear on Front Page Challenge, but his friend declined, asserting ‘they would ask lots of questions and expect me to name names,’ which Wilkinson was not prepared to do.

Spencer acknowledged he always suspected his friend knew more than he ever disclosed about Thomson’s death. ‘I never prodded him for information about Tom Thomson.’

Spencer didn’t show the handwritten letter to anyone for 15 years out of respect for his friend’s privacy. ‘I didn’t want anyone bothering Jack.’

He often wondered what he would do with both letters (handwritten and typed). I’m delighted and grateful that my story in The Record prompted him to call the newsroom. ‘I was waiting for the right time,’ he said.

Spencer asked me what he should do with the letters. He had thought about donating them to a gallery or museum, perhaps the McMichael Canadian Collection or Art Gallery of Ontario. I suggested he donate them to the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound, where my good friend Virginia Eichhorn was director. She was curating Searching for Tom — Tom Thomson: Man, Myth and Masterworks. I arranged a meeting between Spencer and Eichhorn and the two letters subsequently found a permanent home where Thomson was raised — and might be buried.

The letters also led to a bizarre exchange with Roy McGregor. THEMUSEUM had arranged a series of lectures in association with the exhibition. I was invited to give one and was also asked to introduce McGregor, another guest speaker. Prior to his talk we chatted in a coffeeshop along with THEMUSEUM’s chief executive David Marskell.

When talk turned to the letters, McGregor claimed not only to have known about them, but to have dismissed them as irrelevant. To this day I have no idea how he would have known about the letters. They had never been made public. His disconcerting admission was a surprise not only to myself, but to Marskell. I chalked up this obvious falsehood to the egotism of a celebrity journalist. Sad.