Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout these days of mystery devoted to the painter’s life, art and legacy. The sixth instalment, Painting Into the Mystic: Searching for Tom, is based on the review I wrote for the Waterloo Region Record in response to Searching for Tom, an exhibition at THEMUSEUM in early 2011.

We were born before the wind

Also younger than the sun

Ere the bonnie boat was won as we sailed into the mystic

Hark, now hear the sailors cry

Smell the sea and feel the sky

Let your soul and spirit fly into the mystic…

I want to rock your gypsy soul

Just like way back in the days of old

Then magnificently we will float into the mystic….

— Van Morrison

Tom Thomson disappeared under storm clouds on July 8, 1917. As the story goes, the legendary Canadian artist was last seen alive around noon when he set out on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. Although his body was recovered from the warm, shallow lake eight days later, Canadians of all description are still looking for Thomson a century later.

Cloaked in a double mystery of how he died and where he’s buried, the painter haunts the Canadian collective imagination like a restless ghost deprived of peace.

Hell, there’s even mystery surrounding the painter’s famous grey canoe due to conflicting reports of when, and by whom, it was first spotted after the painter’s disappearance and whether it was floating right-side up or up-side down. Moreover, no one has ever revealed what happened to it when it went missing after Thomson’s decomposing body was recovered.

The hunt for Thomson resumed in downtown Kitchener in February, 2011 with Searching for Tom – Tom Thomson: Man, Myth & Masterworks, an exhibition organized by THEMUSEUM in partnership with Owen Sound’s Tom Thomson Art Gallery. The exhibition was curated by Virginia Eichhorn, former curator at Waterloo’s Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery. She had moved to Owen Sound six months earlier to be director and curator at the gallery that bears Thomson’s name on the strength of his growing up in nearby Leith, where he’s believed — by many but not all — to be buried.

This was not the first time Eichhorn — a friend as well as professional colleague — curated for THEMUSEUM. In May, 2009 she organized Talkin’ bout My Generation, an exhibition that introduced the youth of today to the counterculture youth of the 1960s, which coincided with the 40th anniversary of Woodstock, the famous rock concert that took place in Upper State New York. My eldest son Dylan, a high school student at the time, participated in the exhibition. Searching for Tom was the second time the venue extended a welcome mat to a celebrity artist. American Pop artist Andy Warhol was the star of Andy Warhol’s Factory 2009.

At the time, Eichhorn was becoming comfortable with big art shows. In the fall of 2007 she organized Chicago in Glass at the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery, featuring work by one of the 20th century’s most influential artists. Eichhorn befriended the American ‘feminist’ artist and subsequently curated Judy Chicago: A Survey of Important Works, leading to Dauntless: 40 Years of Artmaking and Other Acts of Courage which toured Europe in 2011 before travelling across Canada and the U.S.

The latter part of the last century witnessed a number of retrospective exhibitions on Thomson and the Group of Seven, formed in 1920 three years after Thomson’s death. (Like Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, Thomson died, forever young, at the age of 39.) The retrospectives supported a re-evaluation and critical reassessment of Thomson and the Group as auction prices for their work escalated. The rise continues in 2017.

Searching for Tom, however, surveyed new ground. It did more than explore Thomson’s life, work and death during a formative period in Canadian history when the country was coming of age by beginning to define its national identity. It situated the artist’s achievement in relation to his contemporaries, in addition to current artists inspired, challenged or otherwise influenced by Thomson.

Thomson and the Group fell out of favour in the 1940s when representational painting, especially landscape, was repudiated among artists and critics in the vanguard of abstract expressionism. This movement set the table for colour-field painting, minimalism, conceptualism and other sundry isms. Thomson and the Group, however, enjoyed a revival as the curtain fell on the century with the rebirth of both representation and landscape.

In explaining the exhibition’s title, Eichhorn said her goal was to ‘bring forward the living and ongoing legacy of Tom Thomson as both an important artist and mythic figure who continues to fascinate us.’ For many reasons and in many ways ‘people want to connect with the essence of Thomson.’ (I include myself among these people.)

The exhibition was built around more than 50 Thomson works and artifacts, in addition to work by both historic and contemporary artists from the Tom Thomson Art Gallery’s permanent collection. The Thomson works and artifacts are unique because most were donated by the artist’s family.

The hunt for the elusive painter extended to works on loan from the Art Gallery of Ontario, National Gallery of Canada, Art Gallery of Grimsby, McMichael Canadian Collection and Kitchener’s Homer Watson Gallery, augmented by rarely seen works by Thomson and the Group of Seven from private collectors, some of whom were local.

A speakers’ series accompanied the exhibition. I was delighted to be invited to lead off the series. My powerpoint lecture Fishing for Tom in the Canadian Cultural Landscape traced the legacy and continuing influence of the artist on Canadian arts and letters spanning visual art, theatre, literature and music.

Other speakers included Eichhorn; Matthew Teitelbaum, director and CEO of the Art Gallery of Ontario; Roy MacGregor, author of Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him; Marcel O’Gorman, English professor and director of the University of Waterloo’s Critical Media Lab; Phil Chadwick, forensic meteorologist; Mike Ormsby, heritage canoe expert; Neil J. Lehto, author of Algonquin Elegy; and Ross King, author of Defiant Spirits: Modernism, Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. (To my mind, the best general biography on Thomson and the Group.)

Additional programming bridged disciplines and media including film screenings and live performances with songwriters and composers. There was even a demonstration of tying artificial patterns cast by fly anglers. Yes, Tom was most certainly a fly angler as well as a lure and bait fisherman.

When I interviewed Eichhorn for an article for Grand Magazine, a lifestyle magazine published by the Waterloo Region Record, she confirmed Searching for Tom set out to explore ‘the full gamut of who Thomson was as a painter and as a man of nature.’ It related him to ‘the contemporary artists who influenced him, as well as contemporary artists he influenced.’ The painters who eventually comprised the Group of Seven played prominent roles in both respects.

Echoing a number of cultural commentators and critics, Eichhorn contended that Thomson’s story paralleled Canada’s coming of age. ‘Who we are as a nation is somehow tied up with this artist.’ He not only gave expression to the colour and texture of the Canadian landscape, he ‘captured the spirit of the land in all its rawness and toughness.’

However important Thomson was as an artist who came to embody and reflect the Mystic North, there remains his mysterious death, which casts a long shadow across the Canadian psyche and soul. Whether by accident, misadventure, suicide, manslaughter or murder, ‘a robust man died in the prime of life just as his exceptional artistic potential was blossoming,’ Eichhorn observed.

Indeed, art critics and cultural historians remain enthralled by the intellectual parlour game of speculating how Thomson’s art might have evolved had he not died as his artistic vision was coming into focus, not to mention how that evolution might have determined the course of Canadian art.

Thomson transcended the role of artist. ‘He captured something that spoke, and continues to speak, to the Canadian sensibility,’ Eichhorn affirmed. ‘He remains a powerfully potent symbol of Canada.’

Whatever Searching for Tom revealed about the artist, the curator didn’t lose any sleep over not finding the painter. ‘It’s the search that matters,’ she asserted with a twinkle in her eye.

Indeed, the search continues in 2017 as Canadians commemorate the centenary of the painter’s mysterious death.

As for Searching for Tom itself, it didn’t showcase the iconic masterworks. There was no Northern River or Jack Pine (my two favourite major works), not to mention West Wind. Rather, it offered a glimpse of the artist through lesser-known works and personal memorabilia. It demonstrated how other artists, past and present, responded to the man and the work and wrestled with the myth.

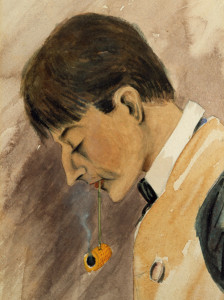

The exhibition featured more than 150 works and artifacts in total. As a starting point, it examined the artist in the context of his time and place. Early works such as Self-Portrait After a Day in Tacoma showed a young, talented artist working to find his own visual vocabulary among sketches, portraits, figurative works, calligraphy and landscapes in the European tradition.

Homer Watson Gallery loaned In Valley Flats Near Doon by Homer Watson, a contemporary whose European style of landscape painting provided an illustrative example of what Thomson and the Group of Seven artists consciously challenged and against which they struggled to define themselves.

The mature works traced Thomson’s career from 1912, when he made his first trip to Algonquin Park, to the fateful summer of 1917, including some completed during his last spring.

It cannot be emphasized enough — his up-close and personal encounter with the provincial park was the single most significant factor in Thomson’s growth as an artist. Had he not visited the park when he did, it’s unlikely he would have left a scratch, let alone an indelible mark, on Canadian art. On the other hand, he might have lived to be a very old man — albeit unknown and forgotten.

The small panels and canvases acted as entries in a visual journal that reflected the painter’s direct and immediate contact with the Canadian Shield — its landscape (especially the convergence of water, shoreline and skies), colours. moods, textures and weather (both inner and outer). They embodied and enacted his struggle to express his intimate connection to nature.

These works were augmented by paintings by his artistic siblings (he grew up in an artistic household), as well as by artists who joined Thomson in Algonquin Park (J.W. Beatty). All of the original Group of Seven, in addition to A.J. Casson, a later member, were represented through oil paintings, watercolours and graphics.

Most welcome was a selection of works by female artists, including Emily Carr, Anne Savage, Hortense Gordon and Prudence Heward. Although contemporaries, these women were not invited into the boys club of Canadian art. Consequently, they were not accorded the appreciation and respect of their male colleagues. Eichhorn made a compelling case for re-examining and reassessing the women as artists in their own right. (It must be noted that Lawren Harris recognized Carr as a creative soulmate upon seeing her work.)

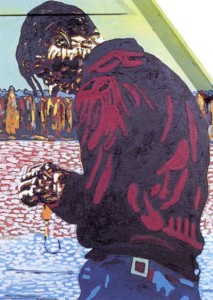

Another major component of the exhibition was work by prominent contemporary and/or practicing artists either inspired by or influenced by Thomson. These included David Bierk, John Boyle, Brian Burnett, Joyce Weiland, Doris McCarthy, Charlie Pachter, Diana Thorneycroft, Harold Town and Allan Harding MacKay, who in addition to being an artist was a former curator at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

These artists fell into two camps. Some paid tribute to the celebrated painter in direct ways, including Burnett, Boyle (Midnight Oil: Ode to Tom Thomson) and Alan Glickman, as well as artist/musician Kurt Swinghammer and Ken Danby. The most provocative defined their work against Thomson and his legacy through irony, parody and satire with their concomitant social, identity and gender critiques. These included Thorneycroft, Weiland, Bierk, David Pellettier and the late Toronto collective General Idea.

Local artists were not snubbed. In addition to Watson (who lived most of his wife in Doon, now a southern suburb of Kitchener adjacent to Hwy 401) and Danby (who lived in a converted mill outside of Guelph), there was Kitchener artist Ed Schleimer (Myth & Legend) among MacKay and Marcel O’Gorman.

Inspired by the iconic Northern River, MacKay’s Source Derivation I: Thomson was an eight-metre long, mixed-media on paper mounted into a corner in the gallery. The large-scale, 45-degree angle painting drew a viewer into itself, much as a forest draws in a wilderness hiker, angler, hunter or portaging canoeist.

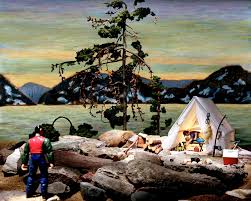

O’Gorman approached Thomson through his famous cedar canoe which, as mentioned above, is cloaked in its own mystery. Commissioned for the exhibition, the performance project/mixed-media, digital installation Myth of the Steersman now rests in the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough.

When I talked to O’Gorman prior to the opening of Searching for Tom, he said the project/installation was intended ‘to breath fire into the myth and the mystery’ surrounding the painter. Inspired by a personal dream (or more accurately vision), the project/installation strummed a new riff on the familiar tune of the canoe in Canadian history, art, literature, commerce and culture, spanning First Nations peoples and coureurs des brois to Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Bill Mason.

O’Gorman fell under the canoe’s alluring spell. ‘The whereabouts of the canoe is as mysterious at the suspicious death and burial location of the artist,’ O’Gorman suggested, referring to the craft at the heart of his project/installation variously as ‘a cyber canoe’ and ‘glowing ghost canoe.’

He began the project by acquiring the same model of Chestnut Cruiser canoe Thomson purchased in 1915 and painted dove grey by mixing a tube of cobalt blue artist paint with a can of canoe paint. Thomson commemorated his distinctively coloured craft with his portrait The Canoe.

O’Gorman contended that the painter treated his canoe as a canvas, not unlike the small boards on which he painted his en plein air landscapes in Algonquin Park. In the process, the artist’s canoe became a moveable landscape within a landscape. ‘Being a painter, he was compelled to paint his canoe.’ As a result, he transformed a manufactured, functional, utilitarian craft into a work of art.

O’Gorman contended that the missing canoe became the equivalent of a missing canvas, not unlike the panels that mysteriously disappeared upon Thomson’s death and remain presumed missing to this day.

Thomson painting his canoe had an element of performance about it that O’Gorman replicated. The Myth of the Steersman began with a canoe being baptized on Canoe Lake, in the vicinity where Thomson’s canoe was found. The baptism was archived with photographs and video.

The performance continued with a canoe being portaged through downtown Kitchener en route to the Critical Media Lab, then located on King Street not far from THEMUSEUM. The portage, a public ritual or ceremony in commemoration of the artist, fused urban with wilderness. It was similarly archived with photographs and video.

When the canoe arrived at the Lab, O’Gorman transformed it into an installation object. This involved wrapping the canoe in fishing line illumined with touch-sensitive light sources — hence creating the aforementioned ’glowing ghost canoe.’

The fishing line could be interpreted literally and figuratively.As already mentioned, Thomson was an avid fisherman. Had he not been, his art would not have developed as it did.

Moreover, when his body was discovered trolling line was wrapped around an ankle, fuelling speculation that his body was deliberately weighed down or anchored after he was either killed or knocked unconscious.

The cocooning process produced a tomb-like object, evoking thoughts of where Thomson’s remains are buried, either in a cemetery on the shores of Canoe Lake, his spiritual home, or in a family plot in a church cemetery in Leith, outside of Owen Sound.

The line wrapped around the canoe also suggested the strings of a mandolin, which Thomson played.

Finally, the fishing line recalls the tradition in Romantic nature poetry of the aeolian harp, which carries various metaphorical and symbolic, even spiritual, associations. One of Thomson’s most iconic paintings, The West Wind, falls within this tradition — as do a number of solitary trees painted by the Group of Seven. When I talked to O’Gorman, he was pleased I had made the connection to the aeolian harp tradition.

After the exhibition opened viewers were invited to interact with the canoe by strumming the fishing line/strings. The project unfolded online on O’Gorman’s website, complete with photos, video, narrative text and blog — hence the designation ‘cyber canoe.’ Visitors to the website were able to manipulate the image of the canoe with their computer mouses, thus participating in the mystery.

Thomson is often depicted as a hewer of creative wood and drawer of artistic water, as raw as the Canadian Shield he painted. Although he was less tutored in fine art and less intellectually honed than other members of the Group, he was far from unsophisticated. By blended traditional and multimedia digital technology, The Myth of the Steersman transfigured the legendary artist into Virtual Tom, fusing past and present, wilderness and city, and literature and music with painting.

It’s not possible to discuss all the works that comprised Searching for Tom; only to say the exhibition was notable for its diversity of form and content, media and technique, not to mention spectrum of critical discourse.

Bierk’s An Allegory of Balances (Oh Canada) After Thomson and de Chirico juxtaposed an image of Thomson’s Jack Pine with an image inspired by the melancholic Surrealist painter. The allegory reminded us that Thomson’s paintings are not only landscapes, but mindscapes and soulscapes.

Thorneycroft’s deliciously tongue-in-cheek Group of Seven Awkward Moments (Jack Pine) reminded us that Thomson was an ordinary man with passions as well as a legendary artist.

Pellettier’s mixed-media, sculptural installation The Adam & Eve Project depicted an elderly couple standing naked in the front of The West Wind. The work implied that the modern day Adam & Eve have been disgraced and expelled from the Garden of Eden because of environmental degradation.

Dennis Tourbin’s Canoe Lake consisted of 32 panels containing fragments of text. The work reinforced the notion that Thomson was a jigsaw puzzle with missing piece which forever prevent us from gaining a complete picture of the man and artist, ensuring that the myth endures.

Danby’s Homage to Tom was especially haunting not only because of its eerie imagery and formal properties, but because of the sad backstory — Danby died of a heart attack in 2007 while canoeing in Algonquin Park.

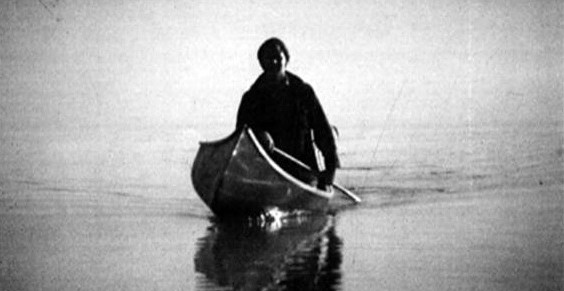

(Featured Image: Artist Doug Dunford captured this ghostly photograph of Tom Thomson in the morning mist on Canoe Lake)