Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout these days of mystery devoted to the painter’s life, art and legacy. The eighth instalment, A River Runs Tom, is an account of the importance of fishing, especially fly fishing, to the development of the painter’s art.

In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing. We lived at the junction of great trout rivers in western Montana, and our father was a Presbyterian minister and a fly fisherman who tied his own flies and taught others. He told us about Christ’s disciples being fishermen, and we were left to assume, as my brother and I did, that all first-class fishermen on the Sea of Galilee were fly fisherman and that John, the favourite, was a dry-fly fisherman.

I am haunted by waters.

— A River Runs Through It by Norman Maclean

. . . fishing with a dry fly, which is the skill that gives both meaning and form to A River Runs Through It, is not labor but an art, not an occupation but a passion, not a mere skill but a mystery, a symbolic reflection of life.

— Haunted by Waters: Norman Maclean, an appreciation of A River Runs Through It by Wallace Stegner

I fell for the work of Tom Thomson many years ago; however, taking up fly fishing just over a decade ago re-ignited my passion for his art.

As much as I admired Thomson’s paintings, he would not have as tight a grip on my imagination, let alone my heart, had he not been a canoeist and fisherman — especially a fisherman. I’m also sure that, while he certainly fished with live bait and hard tackle when they served his purpose, he was also a fly angler.

Thomson is the spiritual guide of the wilderness adventure tradition. Like early explorers, he and the painters who became the Group of Seven canoed and fished on painting trips into the boreal forest of the Canadian Shield. This places Thomson and the Group waist deep in the current of a tradition that flows through Canadian art and culture.

This tradition extends back to early European contact with Fist Nations peoples. It encompasses the exploration of the country and exploitation of its natural resources through westward expansion and frontier colonization. It bridges English and French, Hudson’s Bay traders and coureurs de bois; as well as Grey Owl, an Englishman (Archie Belaney) who reinvented himself as a First Nations man and conservation pioneer.

It continues with such figures as celebrated canoeist/filmmaker Bill Mason; wilderness writer James Raffan, who wrote the biography Fire in the Bones: Bill Mason and the Canadian Canoeing Tradition; and Hap Wilson, a suburban Toronto kid who grew up to become a modern-day Wilderness Man. He was a consultant on the Hollywood film Grey Owl, during which he taught actor Pierce Brosnan how to throw an axe.

Fishing played a significant role in shaping Thomson — the man and the painter. Like the narrator in A River Runs Through It, Thomson grew up in a fishing household. His art would have been much different had he not been a fisherman. In this regard, he shares much in common with the 19th century American artist Winslow Homer (1836-1910).

Homer first visited the Adirondacks to fly fish and paint in 1870. He was 34, about the age of Thomson when he first visited Algonquin Park. Homer continued visiting the area in upstate New York regularly until his death in 1910. Fishing generally, and fly fishing specifically, became one of Homer’s enduring themes and subjects — making him arguably the most accomplished angling artist in the history of the recreational sport. (Homer also fly fished and painted angling subjects in Quebec, Florida and the Caribbean.)

As part of the generation that preceded Thomson’s, Homer was a Realist; a predominantly figurative painter influenced by the French Barbizon School. In contrast, Thomson was predominantly a landscape painter influenced by French post-impressionism, art nouveau, arts & crafts movement and northern European symbolism.

Nonetheless, both developed distinctive, highly personal styles after getting their starts as graphic artists. Both were notoriously tight-lipped about their art. Both painted en plein air before working up finished canvases in the studio — Thomson in Toronto and Homer in New York City.

In addition to the intriguing contact points between the two artists, there are many interesting similarities between Adirondack State Park (constituted in 1892) and Alonquin Provincial Park (established in 1893), including their shared history of logging and recreational tourism in an era of expanding urbanization and industrialization when people sought solace and refuge in the wilderness.

(Interestingly, another painter associated with the Adirondacks, Rockwell Kent, influenced one of Thomson’s closest artist companions, Lawren Harris.)

Celebrated Canadian literary critic Northrop Fyre observed in The Bush Garden that Thomson’s ‘sense of design [was] derived from the trail and the canoe.’ I would add his sense of colour was derived, in part, from the trout he caught in Algonquin Park. The brilliant colours that define his paintings are the colours of lake trout and brook trout — especially brook trout, which is one of the loveliest creatures on this Good Earth. (I believe God will punish humanity for desecrating the planet by calling back all the brook trout. The species is a living barometer of the terrible damage we’re inflecting on the environment.)

Fishing even played a role in the mystery surrounding Thomson’s death. He was reportedly going fishing on the day he disappeared. The importance of fishing to Thomson is indisputable. But determining whether he fly fished has proven less certain.

The most prominent sceptic regarding Thomson’s fly angling is Roy MacGregor. In Northern Light the journalist wants to release his fish and eat it too. Early on he describes a young Thomson as a ‘fine fisherman.’ However, he subsequently sides with the provincial park’s local yokels in dismissing the artist as a fisherman — not to mention canoeist — of ‘average ability.’

I have great respect for MacGregor’s writing. He has his fingers on the pulse of the Canadian collective psyche like few other authors, as reflected in his books about this country including: A Life in the Bush (a beautiful memoir built around a loving portrait of his dad), Escape (an engaging search for the natural soul of Canada), The Weekender (an entertaining cottage journal), Canadians (an affectionate portrait of a country and its people) and Canoe Country (a compelling examination of the making of Canada), not to mention Shorelines (reissued as Canoe Lake), a fictional telling of the alleged romance between Thomson and Winnie Trainor (a distant relative of MacGregor’s). I praised many of these books when I reviewed them as an arts reporter for the Waterloo Region Record.

However, MacGregor sometimes reverts to a pompous, journalistic Johnny-know-it-all. In the case of Thomson’s fly fishing, he gets his line hopelessly entangled in the reel. (Anglers refer to this condition as backlash or bird’s nest.)

He begins by observing that, ‘there was a romancing of Tom Thomson, some justified, some strained, that continues to this day.’ I agree wholeheartedly. But, like a trout in shallow water at the height of day, I get skittish when he implies that those who believe Thomson was a fly angler are ipso facto romancers.

Before setting his hook, MacGregor references a famous photo of Thomson — which appears on his book’s cover — that often misidentifies the spoon he’s handling as an artificial fly. His disdain is obvious when he asserts: ‘… it is clear to anyone who has done any fishing in this part of the country that he is merely attaching a heavy trout lure, known as a spoon, to his line.’

Fact is, this is clear to anyone with a modicum of fishing knowledge — irrespective of whether he or she has ever dipped a line in Algonquin Park — familiar with spoons such as those manufactured by Len Thompson and Williams, not to mention Eppinger’s legendary Dardevle.

MacGregor has fished in ‘this part of the country’ his whole life, which implies he’s an authority. Wrong. His ignorance of fly fishing is self-evident.

’Fly fishing, with its artistic swirls and its own poetic language, is much more esoteric than simply dropping a weighted, triple-hooked, metal lure off the back of a boat or canoe and hauling it about the deep waters in hopes of a strike.’ He’s correct as far as he goes, but soon stumbles. ‘Fly fishing, however, which lends itself magnificently to the cowslip-shouldered streams of Britain and the wide, shallow rivers of Atlantic Canada, is largely a futile exercise.’

Let’s not bother ourselves with the inverse snobbery. While MacGregor describes some of the grace of casting a fly rod, his understanding of fly fishing is superficial. He’s essentially describing one traditional aspect of the recreational sport — casting a dry fly with a floating line upstream at rising trout on a placid river.

Fact is, fly anglers also cast wet flies, bead-headed nymphs and streamers across and downstream. They also cast flies on sinking tip or full-sinking lines with tungsten split-shot (fly angling term for sinkers, just as fly anglers call bobbers indicators), from canoes, kayaks, drift boats, john boats and Adirondack guide boats, in addition to motorized boats.

Thomson might have even used artificial flies in combination with live bait, a practice fly anglers scorn today, but was quite common in earlier times before the catch-and-release gained traction. A friend’s father used to place the fins of the first trout he caught on his flies to increase their enticement. In Ernest Hemingway’s famous story Big Two-Hearted River, the narrator Nick Adams uses grasshoppers on his fly angling rig.

Fly anglers target not only trout, but bass, pike, walleye and musky, among other sports species. They troll from boats on rivers, as well on lakes. Don’t get me started on mighty salt-water species that can weigh as much as 100 pounds.

MacGregor continues to opine: ‘The small hooks of flies that must be tossed back and forth would become hopelessly tangled in the tangle of vegetation that encroaches on Algonquin waterways and surrounds the deep lakes where the lake trout hide.’

Fly anglers do use small hooks — dry and wet fly hooks as tiny as Size 28 (1 mm shaft) which are impossible to hold without tweezers. But they also use streamer hooks as large as Size 2 (nearly 8 mm shaft) that can cause a nasty tear in a hand if mishandled. Flies designed for pike and musky, as well as salmon and salt-water species, can approximate the size of a quarter chicken from Swiss Chalet. They’re deadly and hard as hell to cast. Graceful, they ain’t.

Thomson might have rigged up two or more flies by attaching a dropper fly to the leader on which is attached the main fly. This makes casting awkward. This practice is restricted in some catch-and-and-release areas where single, barbless hooks are mandatory, but is allowed in Algonquin Park.

Similarly, a fly angler gets entangled in all manner of vegetation — weeds, bullrushes, bushes, lily pads, trees, fallen logs and other debris — not to mention human ears and other creatures, wherever he or she fishes — unless it’s offshore on a lake or in the middle of a wide river. That’s why fly anglers rely on various casts that eliminate back casts — the roll cast being the most common.

Anyway, is the bush in Algonquin any thicker or any denser than the forests of Algoma or North of Superior which are popular fly fishing destinations, as well as locations made famous by the Group of Seven?

MacGregor thinks he’s landing his big fish after casting at film criticism. ‘Had Norman Maclean been writing about trolling, rather than fly fishing, in a A River Runs Through It, it’s doubtful that he would ever have found a publisher — and unimaginable that Robert Redford and Brad Pitt could have turned the book into a classic movie.’

Following this specious reasoning, it’s any wonder John Huston and Gregory Peck bothered with a cinematic adaption of Moby Dick, not to mention John Barrymore and Patrick Stewart who starred in other films of Herman Melville’s masterwork. Ditto: Spencer Tracy in John Sturges’ 1958 cinematic adaptation of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.

A River Runs Through It is a ‘classic movie’ not primarily because it celebrates fly fishing (as does Maclean’s lovely novella), but because it tells a compelling multigenerational family saga and coming-of-age story with themes that touch the human heart. Its screenplay is faithful to Maclean’s elegiac novella and it features good acting and evocative cinematography.

(As good as the film is, I highly recommend Maclean’s pastoral novella. It’s both richer and deeper than the film. I similarly recommend two fine appreciations: Wendell Berry’s Style and Grace, collected in What Are People For, and Wallace Stegner’s Haunted by Waters: Norman Maclean, collected in Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs.)

Of course, MacGregor knows this, but he’s too hopelessly entangled in his own narrative to acknowledge it.

Fact is, I know many fly anglers who have fished in Algonquin. Dan, my closest fly fishing companion, and his longtime angling friends Jeff and Craig have been fly fishing in the park for a quarter century. Obviously they’ve never crossed fly lines with MacGregor.

As mentioned above, MacGregor is not an academic; he’s a journalist. Further, when it comes to Thomson, he’s an adversarial journalist with a stake in advancing a personal narrative rather than weighing and balancing all the available documentary evidence. Still, it’s disconcerting what he chooses to ignore or dismiss when it repudiates the World of Algonquin According to Roy.

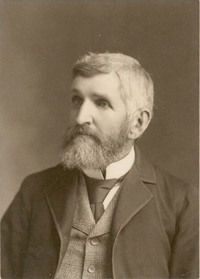

I can’t believe he’s unfamiliar with John D. Robins’ The Incomplete Anglers — either the original 1943 edition or 1998 Friends of Algonquin Park reprint. Robins, an enthusiastic champion of Canadian art, was a close friend of Group of Seven member Lawren Harris. Moreover, his Governor General award-winning memoir was illustrated by Franklin Carmichael, another Group member

The book chronicles a canoe and fishing adventure Robins — an English professor along with Northrop Frye at Victoria College at the University of Toronto — made with his brother Tom. Although Tom fished with live bait exclusively, the author was a devoted fly angler.

The Incomplete Angler is one of a trio of fly angling memoirs to win Governor General’s awards. David Adams Richards’ Lines on the Water: A Fisherman’s Life on the Miramichi and Roderick Haig-Brown’s Saltwater Summer also won the prestigious non-fiction literary award.

The references to fly fishing in The Incomplete Anglers are far too numerous to delineate. In an early passage Robins lists the flies he wants to purchase — including such classic dry and wet flies and streamer patterns as Silver Doctor, McGinty, Caddis Drake, Parmcheenee Belle (now spelled Parmachene Belle), Royal Coachman (a famous brook trout pattern) and red hackle (one of the oldest known patterns).

Later he confides: ‘I was prepared to worship fly fishing with a pure, exclusive devotion and leave the worms behind. I supposed that true angling aristocrats would be puzzled by the mention of worms in connection with fishing. But Tom swore that he would have nothing to do with flies.’

Thomson strikes me as more accommodating in response to piscatorial circumstance than either Robins brother. But the point I’m really making is that fly fishing was practiced in Algonquin Park despite what MacGregor knows personally of anglers who fished solely with live bait and/or hard tackle.

I acknowledge the quarter century between Thomson’s death and the Robins’ Algonquin wilderness adventure, but the time span is irrelevant. Fly fishing was established in the park long before Robins followed Thomson’s example of paddle and fly rod.

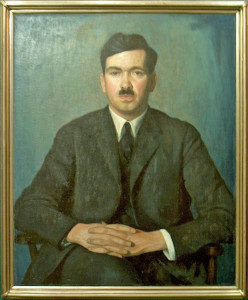

John D Robins (1925), one of 10 portraits painted by Lawren Harris in the 1920s, collection of University of Toronto Art Centre

Thomson would have been introduced to fly fishing as a guide in Algonquin Park when wealthy Americans traveled North to enjoy a Canadian ‘wilderness’ experience. American anglers would have been familiar with the fly angling traditions emerging in Pennsylvania, the Catskills and the Adirondacks. The years Thomson spent in the provincial park overlapped the years now celebrated as the Golden Age of American Fly Fishing, when the legendary Theodore Gordon was popularizing the sport. Innovative, master craftsmen Leonard, Payne and Edwards et al had been making split-cane bamboo rods for a quarter century, while Mary Orvis Marbury was collecting American flies for her seminal book Favourite Flies & Their Histories.

In his 1996 pictorial historical book Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park: Tom Thomson and Other Mysteries, S. Bernard Shaw refers to Joseph Adams. The English fly angler and columnist for the prestigious sporting magazine The Field visited Algonquin Park in 1910 for the expressed purpose of casting fur and feather. Shaw records: ‘[Adams] hired park ranger Mark Robinson, an excellent man well acquainted with the forest, to guide him on an expedition to the Oxtongue River to fly fish for brook trout. . . He had great success . . . catching trout with his ten-foot cane-built rod and gut [line] casting [a] silver doctor and march brown (artificial flies).’

Adams would have come to Algonquin steeped in English fly fishing lore and tradition, including the concept of matching the hatch and the celebrated debate, raging at the time on both sides of the Atlantic, over the supremacy of dry fly versus wet fly, spearheaded by two of the recreational sports’ greatest figures — Frederick Halford and G.E.M. Skues, respectively.

The origins of matching the hatch extend back to at least 1643 when Gervase Markam recommended catching flies that were hatching and imitating them. The concept didn’t gain traction, however, until 1836 when Alfred Ronalds published his seminal The Fly Fisher’s Entomology. An aquatic biologist and illustrator, Ronalds applied scientific nomenclature to insects of interest to fly anglers and, in the process, established a direct link between entomology and fly fishing. (North American fly anglers had to wait a century until Preston Jennings published A Book of Trout Flies in 1935.)

Mark Robinson (left) & Joseph Adams, Algonquin Park Archives. Adams was a British author who included a description of his time fishing with Robinson in his book Ten Thousand Miles Through Canada, published in 1912

I recently visited the Algonquin Park Visitor Centre to check out a modest exhibition Algonquin Park in the 1910s — A Tom Thomson Perspective. I took the opportunity to peruse the centre’s archival photographs dating from when Thomson was in the park and — as expected — saw a number of images of anglers with bamboo fly rods, resembling the one Thomson is casting at Tea Lake Dam.

The mystery of whether Thomson ever fished with a fly rod and tied artificial flies would likely have been solved had many of his personal belongings not disappeared upon his death. A candidate for light-fingered culprit is Shannon Fraser, owner of Mowat Lodge and a prime suspect in a list of those alleged to have either accidentally killed or deliberately murdered the painter.

Remnants of fur (I recently used a fly in the Adirondacks made from coyote, raccoon and muskrat), feather, yarn, thread or other fly tying material would have settled the matter. But these — providing they existed, of course — disappeared along with Thomson’s canoe and paddle, not to mention some painted boards. The tying materials would not have been taken because they were valued as artifacts of a great artist, but because they would have been considered useful.

Nonetheless, there’s abundant documentation that Thomson did, at least when it teased his inclination, fish with a fly rod and artificial flies. I would bet my monthly pension cheque that he fished traditional wet flies downstream and likely fished large, bushy, dry flies as wet flies.

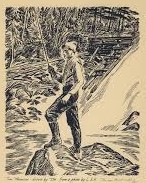

There’s conclusive proof of Thomson fly fishing in a photo of the painter at Tea Lake Dam taken in 1916 by his friend and fellow artist Lawren Harris. Thoreau MacDonald, son of J.E.H, MacDonald and a fine printmaker and illustrator in his own right, based a later sketch on the photo.

Given MacGregor’s knowledge of fishing, he should recognize Thomson is holding a fly rod rather than a bait-caster (spinning rods were not invented until the Second World War in Europe). He also should recognize that Thomson is stripping in line in accordance with fly casting practice. Why he ignores this documentary evidence is beyond me.

The photo adorns the cover of Gregory Klages’ The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction, one of the most recent studies about the painter — and essential reading.

Returning to the photo MacGregor mentions in Northern Light. It was taken by Fred Varley’s wife Maud in 1915. Many of the captions or cutlines that accompany the photo misidentify the terminal tackle as an artificial fly. In fact, he’s tying on a spoon, likely one made by his own hand. The photo adorns the covers of Northern Light and Sherrill Grace’s Inventing Tom Thomson: From Biographical Fictions to Fictional Autobiographies and Reproductions, as well the back cover of the Tom Thomson retrospective exhibition catalogue.

Despite McGregor’s implication that the photo somehow proves Thomson was not a fly angler, it does nothing of the kind. It simply confirms that the artist sometimes used spoons as terminal tackle, which no one disputes.

Perhaps the most perplexing willful oversight on McGregor’s part involves a photo that he spends a great deal of time analyzing in Northern Light. It’s a photo Thomson took of a woman who McGregor insists was long misidentified as Winnie Trainor of Hunstville and Canoe Lake.

Irrespective of the woman’s identity, which remains unknown, and the fact that she’s wearing a wedding band, one thing is unmistakable and undeniable: what she’s holding in her hands — in her right is a brace of smallmouth bass; in her left is a bamboo fly rod. Yes, a bamboo fly rod.

How does McGregor not identify the rod for what it is? Instead he erroneously mislabels it ‘a fishing pole.’ It’s possible the woman caught the fish, perhaps Thomson acted as guide. But more likely, considering women did not fly fish in significant numbers until after the First World War, the answers to the questions of who caught the fish and who owns the fly rod points to one person. The man holding the camera.

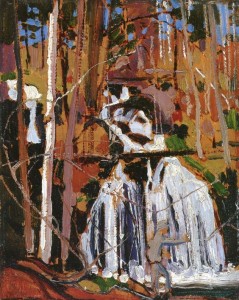

Thomson painted a fly angler, at least once that we know of, in The Fisherman (winter of 1916-17), which is in the permanent collection of the Edmonton Art Gallery. I have not been able to identify the angler, if in fact the painting is based on an actual fly fisherman. It could just as easily be a purely imagined self-portrait: the fly angler as artist and/or the artist as fly angler.

Thomson painted a less distinct fisherman in Little Cauchon Lake, but it’s impossible to determine the kind of rod he is using.

I might be casting on shallow water here, but I suspect Thomson tied his own flies based on close observation of insects two decades before Jennings published his seminal Book of Trout Flies in 1935, not to mention almost half a century before Ernest Schwiebert published Matching the Hatch in 1955, followed in 1969 by Art Flick’s Streamside Guide to Naturals and Their Imitations. Imagine what Thomson’s artistic eye and nimble fingers would have brought to fly tying.

To fuel speculation about Thomson as a fly fisherman, A.Y. Jackson’s maternal grandfather, Alexander Young, the first principal at Kitchener’s Suddaby Public School, was both a noted entomologist and a fly fisherman. His knowledge of insects might well have been passed on to Thomson had the two men ever met.

Even if Thomson and Young never met, Jackson most assuredly would have informed his close friend about his grandfather, perhaps while sitting around the campfire after a day’s painting or fishing, glowing pipe in one hand and tin cup of whiskey in the other.

When Thomson moved to Toronto in 1905 and started working in commercial art he spent time with a relative we know as ‘Uncle’ William Brodie. Brodie, who might well have been a cousin, was a prominent naturalist specializing in entomology. He helped found the Toronto Entomological Society in 1878 and, from 1903 until his death in 1909, was director of the Biological Department at the Ontario Provincial Museum (later the Royal Ontario Museum).

The time Thomson spent outdoors with Brodie nurtured the fledging painter’s passion for nature. The entomology he learned from Brodie, which included how to collect study specimens, would have served him well fly fishing in Algonquin Park.

Early Thomson biographers associated the painter with fly fishing. It’s disconcerting that McGregor wilfully ignores these earlier documentary references. It might well be he dismisses the biographers as ‘romancers.’ The problem is that fly fishing was neither idealized nor romanticized at the time; it was simply another way of catching fish. Spin casting rods and reels were all the rage.

Ottelyn Addison (daughter of Algonquin Park Ranger Mark Robinson) in collaboration with Elizabeth Harwood observe in their 1969 book Tom Thomson: The Algonquin Years that, ‘Thomson was a fly fisherman of exceptional skill.’ (Italics mine) They quote Park Ranger Tom Wattie as saying, Thomson ‘could cast his line in a perfect figure eight and have the fly land on the water at the exact spot planned.’ (Italics mine) In addition to being a park ranger, Wattie was an avid fisherman who would have recognized fly angling.

Addison (who also wrote Early Days in Algonquin Park) continues: ‘[Thomson] knew trout have to be down in the cold water in summer; he looked for rocky shelves where they loiter; he studied their habits, observed them feeding.’ Fly anglers will readily identify with this behaviour.

Finally, a footnote in The Algonquin Years includes a March 16, 1913 letter from Leonard Mack, a self-described ‘fishing companion’ of Thomson’s who refers to a fishing trip the previous summer: ‘I was under the impression that we took a photo of you fly casting from a rock on Crown Lake but perhaps we used your camera.’ (Italics mine) Sadly, most of Thomson’s photographs, like many of his personal effects, did not survived.

The piscatorial plot began thickening previously with Audrey Saunders’ Algonquin Story, originally published in 1946 and reprinted in 1963. Saunders, a pioneer in both oral history and Canadian studies, taught at Montreal’s Dawson College and Sir George Williams University (now Concordia).

She refers to the photo of Thomson at Tea Lake Dam: ‘Although there is no date to indicate when the photograph of Tom Thomson fly-fishing at the bottom of a lumber dam was taken, there is no doubt that this shows one of his favourite pastimes in the Park. There are many stories of the good fishing to be found near the old dams, and certainly, the intent of concentration expressed both in Tom’s face, and in his stance on that particular occasion, are eloquent of his interest in the art of angling.’ It’s a concentrated stance any fly angler would recognize as his own.

In the book there’s also an archival photo, circa 1911, with a caption of ‘Fishing trip in Algonquin Park,’ that shows one of six men (fourth from left) holding two fishing rods, one of which is clearly a fly rod.

Even more significantly, we find an intriguing description of Thomson. ‘Tom’s skill at fly casting won him the admiration of the guests at Shannon’s (Mowat Lodge)…. He made his own flies and bugs, watching to see what insects made the fish rise, and painting his own imitations on the spot.’ (Italics mine)

This single sentence might well be the smoking piscatorial gun — excuse the mixed metaphor.

It confirms that Thomson — who undoubtedly fished with natural bait and hard lures when it suited his needs or when conditions dictated — not only made his own lures, but tied his own flies. The reference to Thomson observing insects that made fish rise and then painting pictures of them on the spot — presumably so he could tie flies later to match the hatch — would place him at the forefront of what became one of the most significant developments in fly angling not only in the 20th century but in the long, storied history of the recreational pastime.

It’s not Northern River or The Jack Pine or The West Wind, but it’s still exciting and significant — at least for fly anglers with an interest in the sport’s tradition, history and heritage.

Even if he didn’t tie his own flies to match the hatch, it’s as clear as a freestone stream that a river did run through Tom Thomson.

Tom Thomson & Fly Angling Literature in Canada

Although not a direct influence, Thomson casts an inspirational line across Canadian fly fishing literature, both fiction and creative non-fiction. I often wonder what Thomson thought about fishing but, like every aspect of his life, he didn’t leave much of a written record.

With the exception of works by John Buchan, the following books are from my personal library. They comprise a representative cross-section of some of the best Canadian fly angling literature.

Canada’s 15th Governor General, John Buchan (1875 – 1940), was a prolific Scottish author (novels, short stories, poetry, biography, memoir and general non-fiction), historian and editor, in addition to Unionist politician who served as Governor General from 1935 to 1940. He was also an avid fly angler who wrote frequently about the outdoors and the recreational sport (A Lodge in the Wilderness and John Macnab). He also edited the 1901 edition of Izaac Walton’s Compleat Angler.

However, this sub-genre of Canadian outdoors literature is led by New Brunswick’s David Adams Richards. Lines on the Water is one of the most elegant memoirs about fly fishing written by a Canadian. As mentioned above, it garnered a Governor General’s Award for non-fiction. Richards also wrote Facing the Hunter: Reflections on a Misunderstood Way of Life, a provocative memoir about hunting.

Before Richards, Newfoundland writer Frank Parker Day, author of Rockbound, penned The Autobiography of a Fisherman, in 1927.

The late Paul Quarrington, a prolific author, songwriter and performer, wrote two comedic books about fishing and friendship (Fishing with My Old Guy and From the Far Side of the River), as did his fishing/writing pals Jake MacDonald (Raised by the River, Houseboat Chronicles and With the Boys: Field Notes on Being a Guy), Chris Gudgeon (Consider the Fish: Fishing for Canada from Campbell River to Petty Harbour) and David Carpenter (Courting Saskatchewan: A Celebration of Winter Feasts, Summer Loves and Rising Brookies). MacDonald also edited an excellent anthology of angling creative non-fiction Casting Quiet Waters: Reflections on Life and Fishing.

British Columbia-bred and Edmonton-based Tim Bowling has written about fishing in his poetry (Fathom), novels (The Paperboy’s Winter) and non-fiction (The Lost Coast: Salmon, Memory and the Death of Wild Culture).

Fishing also inspired the late political pundit Charles Lynch (Fishing with Simon), public philosopher Mark Kingwell (Catch & Release), versatile writer John Craig (Some of My Best Friends Are Fishermen) and West Coast newspaper journalist Mark Hume (River of the Moon: Seasons on the Bella Coola). Peter Thomas, a former English teacher at the University of New Brunswick, wrote a history of salmon fishing in the province with the wonderful title of Lost Land of Moses: The Age of Discovery on New Brunswick Salmon Rivers.

Ehor Boyanowsky, a criminal psychologist and professor who has written extensively about fishing and conservation, penned Savage Gods, Silver Ghosts: In the Wild with Ted Hughes, an affectionate memoir about fly fishing for steehead on the West Coast with the English poet laureate.

One of Canada’s most beloved newspapermen Gregory Clark wrote extensively about fishing, including fly fishing — he played a role in naming one of the most famous streamers, the Mickey Finn). His angling collections include Fishing with Gregory Clark, Greg Clark & Jimmie Frise Go Fishing and Outdoors with Gregory Clark

Last, but definitely not least, there’s the dean of fly fishing writing — Roderick Haig-Brown, whose books on fish, fly fishing and conservation are celebrated among fly anglers around the world. Of his many books my favourites are Measure of the Year, The Seasons of a Fisherman: A Fly Fisher’s Classic Evocations of Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter Fishing, A River Never Sleeps (with introduction by Nick Lyons and afterword by Thomas McGuane), A Primer of Fly Fishing and To Know a River: A Haig-Brown Reader, as well as From the World of Roderick Haig-Brown: Writings & Reflections.

(Featured image of photo of Tom Thomson fly fishing at Tea Lake Dam taken by Group of Seven founding member Lawern Harris)