Over three decades as an arts reporter for the Waterloo Region Record I wrote more about Ken Danby than any other artist, with the possible exception of Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven.

I visited him at his renovated Armstrong’s Mill home/studio outside of Guelph multiple times. I also visited his wife Gillian on a couple of occasions after her husband’s premature death — initially when she was preparing a posthumous exhibition (reviewed below) and later when she was in the process of selling the picturesque property — eventually purchased by Jim Balsillie of Blackberry renown.

I like Danby’s art and I liked the man. I’m delighted he appreciated the reviews I wrote. He never failed to express his gratitude with a hand-written note, signed exhibition poster and annual desk calendar delivered before Christmas by Canada Post. Whenever he mounted an exhibition, he guided me on a private tour of the work. Whenever we met socially he always initiated a brief chat.

I was shocked when I learned he had died — much too young — of a massive heart attack on 23 September, 2007 while canoeing in Algonquin Park. I was deeply honoured to receive from his family a personal invitation to the memorial celebration of his life and art at Guelph’s River Run Centre.

BEYOND THE CREASE: KEN DANBY

Art Gallery of Hamilton

On view through January 15, 2017

KEN DANBY: FIVE DECADES

Guelph Civic Museum

On view through January 15 2017

The Art of Gallery Hamilton and Guelph Civic Museum are presenting a pair of exhibitions in tandem. Viewed together they constitute the most significant retrospective of Danby’s work yet mounted by public galleries. The exhibitions acknowledge the 10th anniversary of the artist’s death. Moreover, the partnership marks a seminal point in the overdue appraisal of an artist who was generally shunned by art institutions in his lifetime, despite achieving enormous popular success (with both the public and collectors).

Beyond the Crease: Ken Danby, co-curated by McMaster University’s Ihor Holubizky and the AGH, and Ken Danby: Five Decades, curated by Judith Nasby, curator emerita of the Art Gallery of Guelph (formerly Macdonald Stewart Art Centre), continue concurrently through 15 January, 2017.

Spanning four decades, the exhibitions trace Danby’s practice and career as a realist painter, watercolourist, printmaker (both serigraphy and lithography) and commercial artist. They reflect an artist whose brush gave expression to a range of Canadian themes, iconography and ideals.

The exhibitions confirm his skills as a meticulous draughtsman and accomplished technician with an astute formal eye. They encompass his chosen subjects — beginning with early images of rural and small-town life in southwestern Ontario through late landscapes of Northern Ontario and Western Canada, in addition to portraits, nudes and images of sports and athletes.

Beyond the Crease features 70 works from private and public collections (including National Gallery of Canada, Vancouver Art Gallery, Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Musee d’art contemporain de Montreal and National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington) and Danby Estate. In addition, the exhibition introduces a video about the artist produced by his eldest son, filmmaker Sean Danby.

Beyond the Crease draws its title from the 1972 painting At the Crease, which depicts an anonymous hockey goalie. Not only is it one of the best-known images in Canadian art, reaching the status of national icon, I believe it’s a sly self-portrait of the artist.

Ken Danby: Five Decades features work on loan from the Art Gallery of Guelph and University of Guelph, as well as corporate collections and Danby Estate. It includes the first public showing of the mechanical easel the artist designed to orientate his painting surface towards the changing conditions of natural light and never-before-seen views of the Canadian Shield where his untimely death occurred.

The pair of exhibitions mounted in the region where Danby lived most of his life and celebrated through his art-making, is a worthy prelude to the ‘scholarly retrospective at a major public gallery’ I called for in my 20 October 2007 appreciation.

Consequently, I’m taking the opportunity afforded by Beyond the Crease: Ken Danby and Ken Danby: Five Decades to retrace what I wrote about an artist I admired and respected. I think it offers a sympathetic overview of his oeuvre. It certainly reflects the ongoing conversation I conducted with Ken over the years. The pieces appear in reverse chronological order, beginning with the most recent.

In fairness I must issue a warning: this is a long blog posting. My defence is simple: Ken Danby deserves the attention which negates any apolology I might otherwise offer.

Dateline: 5 June 2010

REMEMBERING KEN: POSTHUMOUS EXHIBITION

Ken Danby was a meticulous artist who applied the same care and attention to exhibitions he did to his works of hyper-realism. Before his unexpected death, he oversaw all aspects of his exhibitions.

Danby’s wife Gillian, his muse and model, and Greg McKee, his studio assistant for 28 years, are working with Toronto’s Odon Wagner Contemporary Gallery to ensure the artist’s exacting standards are maintained in the first exhibition of paintings and drawings since his death.

Wagner, who has been exhibiting realistic art for four decades, presented a Danby exhibition in the fall of 2008. But it was restricted to lithographs and serigraphs. This exhibition showcases 53 oil and egg tempera paintings, as well as watercolours, sketches and preparatory studies. Many works are from the artist’s estate. ‘The exhibition is scholarly in that it offers insight into the artist’s oeuvre,’ Wagner notes.

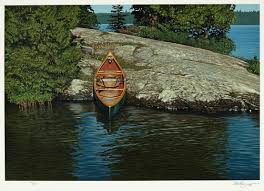

Spanning 35 years, the exhibition includes landscapes and portraits, in addition to images of horses and sports (rowing, sailing and hockey). Some works were still in Danby’s studio when he died. Six paintings remain unfinished (Temagami Channel, Inland Sea, Parking Entrance, Sisters, Remnants and North of Superior), but are included because they open windows onto Danby’s creative process, says Wagner. The exhibition is enhanced by a quintet of ‘iconic’ works — At the Crease, Pancho, Stratford Swans, Island Reach and Near Dusk — on loan from private collectors.

‘Some of the pieces have never been seen in public,’ confirms Gillian Danby, who concedes that mounting the posthumous exhibition has been bittersweet. ‘Some of the drawings come from Ken’s personal collection.’ Others ‘on loan have not been exhibited since they were purchased.’

Danby’s art rose in stature following his death and its value increased accordingly. Nonetheless, his wife says prices have been set to appeal to ‘as wide a range of people as possible. It’s what Ken would want,’ she asserts.

Many of the most recent works feature imagery of Northern Ontario, including Algoma and Temagami, as well as Algonquin Park where the Danbys regularly canoed.

Born and raised in Sault Ste. Marie in 1940, Danby didn’t paint the North until after his father died in September, 1994. It was the landscape of southwestern Ontario around his converted-mill estate that stoked his creative imagination. ‘After his father died Ken returned to the old camp where his family hunted and fished,’ Danby’s widow recalls. ‘That triggered thoughts of family and childhood.’

A year later he painted Northland, a vista of Northland Lake where his grandfather owned property, marking the artist’s return to his birthplace in creative terms.

The Danbys began going on canoe trips throughout the North. But like many Northerners, the artist maintained an uneasy relationship to water. ‘He never felt comfortable on the water,’ confirms Danby, who was raised in North Bay after emigrating from England. ‘I taught Ken to be more at ease.’

Her husband became a master at painting what he instinctively feared. ‘Ken painted water so wonderfully,’ Danby observes. ‘Nobody painted water like him.’ While the artist enjoyed hockey and skiing, he was introduced to kayaking and canoeing by his wife, an avid skier and horsewoman.

Initially Danby had not planned to accompany his wife and others on what turned out to be his last canoe trip. ‘We had been out two weekends earlier, but the weather was so inviting he decided to join us.’ One of the canoeists in the party was a descendent of Lawren Harris, a founding member of the Group of Seven. They stayed a night in a cabin owned by the Harris family. ‘We joked about reliving history,’ Danby recalls with a reflective smile.

On the day of her husband’s fatal heart attack, the party set out for their destination under sunny skies. But ‘the campsite was further away than we expected.’ As the party pulled up to the site, Danby’s canoe capsized. ‘He was gone by the time we got him to shore, but we didn’t know that at the time,’ Danby confirms.

It took four hours for paramedics to arrive by helicopter. Meanwhile, Danby cradled her husband in her arms. ‘A three-quarter moon came up. It was so peaceful. He didn’t suffer. I’m so grateful for that.’

The incident took place on North Tea Lake, not far from where legendary painter Tom Thomson drowned on Canoe Lake 90 years previously under suspicious circumstances. Danby says her husband was interested in Thomson, an early artistic hero. In 1997 he painted Algonquin. Subtitled In Homage to Tom Thomson, the oil on canvas shows a lone canoeist at night on Cache Lake, in Algonquin Park.

Very much the tough Northern pragmatist, the artist didn’t have much time for the mystery of where Thomson is buried – whether in Algonquin Park or in the family plot in Leith Cemetery, outside of Owen Sound. ‘Ken did a lot of research on Thomson. He supported solving the mystery with scientific evidence. He believed we don’t need the mystery because we have the paintings.’

As Danby recalls the events of 23 September, 2007, she refers to True North, a serigraph her husband completed in 1998 showing a lone green canvas canoe pulled up on the shore of Lake Temagami. Looking back on that fateful canoe trip, she reflects: ‘It’s as though Ken paddled himself into his own painting.’

Dateline: 20 October 2007

THE NORTH CALLS KEN DANBY HOME

The North gave us Ken Danby and the North called him home. That circle of completion would have appealed to an artist whose sense of balance, detail and precision defined his art. It also would give comfort to an artist who would rather discuss his work or one of his enduring passions, hockey, than spirituality.

Danby’s birthplace of Sault Ste. Marie exerted a profound influence on both the man and the artist. Nonetheless, it was the landscape of southwestern Ontario around his home outside of Guelph that fired his creative imagination when he became a realist artist in his early 20s.

The landscape of southwestern Ontario dominates his early works — think of them as visual manifestations of Alice Munro’s short stories — on view at the MacDonald Stewart Art Centre. The exhibition Ken Danby 1940-2007, was mounted just two days after the artist’s sudden death. It features 15 works from the permanent collections of the art centre and University of Guelph, augmented by 23 works from the artist’s collection.

The exhibition doesn’t pretend to be more than a tribute to Danby’s life and art. Still, many of the works reveal a recurring preoccupation that shaped his art. The works encompass various media including egg tempera, an early favourite, as well as watercolour, acrylic, oil, serigraph and lithograph. Irrespective of media, Danby’s approach remained remarkably consistent. His attentiveness to detail and texture was highly accomplished.

Guelph Carousel, a 1977 watercolour, shows a youngster on, you guessed it, a carousel. Danby often returned to the landscape and the people closest to him as subjects for his art — particularly his three sons (Sean, Noah and Ryan) when they were young as well as his wife.

Gillian is obviously the subject of the egg tempera Into the Sun, which shows a nude woman holding a clear glass skull concealing her breasts. Danby, himself a ruggedly handsome man, was very much aware of his wife’s physical appearance and he affectionately and unapologetically celebrated her beauty in numerous works which, while erotically evocative, are never prudent. He commemorated his wife’s singular beauty without idealizing Beauty. He was drawn to the real rather than to the classical.

Danby went against the grain celebrating physical attractiveness when much leading art was preoccupied with ugliness, aggression, violence and vulgarity. He also turned a deaf ear to anxieties regarding the exploitation and commodification of female models under the brush of male artists. He never objectified his wife’s beauty. However, he took a big risk at a time when critics were devoted to feminist politics and championed an array of contemporary ‘isms’ that had no time for nudes — conceptualism, formalism, deconstructionism and postmodernism.

Danby dared to be a Romantic in unromantic times. It’s interesting to contrast his representations of his wife/model to a couple of other contemporaries who created enduring images inspired by spousal models.

The late Alex Colville’s wife/model Rhoda was primarily form, almost sculptural (think the sculpture of Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth transferred onto canvas). In contrast, Danby’s wife/model was subject.

The late Greg Curnoe — a cornerstone of London Ontario’s thriving arts scene until his untimely death — created a controversial series of portraits of his wife/model Sheila that were so open and unguarded, more naked than nude, as to constitute an invasion of privacy. In contrast, Danby often employed a visual dynamic of simultaneously revealing and concealing. He used this technique in Cooling Off, which shows a girl dangling her feet in a pool of water. Her identity remains a mystery, allowing her to become emblematic of girls on the brink of sexual awakening.

Danby explored the similarities between art and sport. He created images of anonymous athletes and paid tribute to some of the great ones, especially hockey players (Gordie Howe, Bobby Orr, Tim Horton, Wayne Gretzky). The exhibition features selected representational Olympian athletes from a large series of serigraphs (The Diver, The Vaulter, The Sculler, The Hurdler).

An early watercolour Pulley Wheel reflects Danby’s interest in the rural life of southwestern Ontario — which invites comparisons to American realist Andrew Wyeth. It also shows how he pared images down to their essentials and exploited the visual tension between light and shadow, known as chiaroscuro.

The importance of light in Danby’s art is illustrated in the oil painting of Gordon Lightfoot, the Canadian music icon he befriended in Yorkville in the 1960s. The portrait is backlit, which puts the white suit Lightfoot is wearing in heightened relief. The painting draws attention to Lightfoot’s hands, which wrote the songs and played the guitars.

Danby gives his model a bemused, slightly askew smile. Although the result of a bout of Bell’s Palsy earlier in his career, Lightfoot’s smile works on a metaphorical level, bespeaking a modesty he has never forsaken. Both the artist and the songwriter retained the small-town values that found expression through their respective art forms.

Finally there’s something eerily prescient about the portrait. Although completed in 1988, it seems to anticipate Lightfoot’s brush with death in 2002. This might sound far-fetched. Still, to me this is a portrait of a man who approached the edge and backed away before it was too late. I know this reading is advanced from the vantage point of hindsight. But this interpretation explains not only the evocative halo-like backlighting behind Lightfoot’s head but the bemused smile of a man who knows something we don’t. It’s the smile of a man who has stared down death.

I believe this is where Danby’s work reflects an apprehension of the spiritual. It’s non-ecumenical, subtle rather than overt, more a feeling of something ineffable than a declaration of faith or an assertion of belief.

At the Crossroad, a seminal, 1969 egg tempera, anticipated a recurring theme of spirituality in Danby’s work. As its title denotes, the painting consists of a farmer standing at a rural crossroads. It’s late spring or early fall, the time of planting or harvesting. He’s middle-aged, a man of the soil bridging metaphorically the transition from independent family farm to international agribusiness. More subtly, the painting suggests multiple associations connected to the crossroads — the road taken and not taken — with their intimations of mutability and mortality.

Other works deal with themes that can be broadly described as spiritual. A couple of watercolour studies of Stonehenge underscore the ancient site’s significance which incorporates the sunlight of changing seasons, suggesting a sacramental, ritualistic or ceremonial purpose. Similarly, The Offering shows a young Polynesian woman offering flowers in some sort of ritual.

In later works Danby’s sense of the ineffable could be too self-conscious. The Great Farewell shows Wayne Gretzky, aka the Great One, waving to fans at Madison Square Gardens, bringing the curtain down on his illustrious hockey career. Instead of having spectators in the background, Danby superimposes the actual configuration of the stars over New York City at the precise moment Gretzky left the ice. Danby’s astronomical research is exact, but, to me, the juxtaposition of a retiring athlete and the starry heavens is heavy handed. Danby works too hard for effect.

Now that Danby is gone, thoughts arise about his legacy. He was athletically prolific, producing an average of a new image every three weeks throughout his 45-year-career. His admirable work ethic resulted in the production of some banal images, which was both unavoidable and regrettable.

Nevertheless, he created a number of images that endure as national icons reflecting this country’s collective psyche and soul. And he achieved this on his own terms; against the grain of high art bias and to the delight of ordinary people without specialized training in the fine arts. Danby challenged the art establishment and won. He remained true to his creative impulses and dictates; he stayed the course and gave legitimacy to realism in an abstract age. And enjoyed the prestige and wealth that reward popular appeal.

It’s time to reassess Danby’s art minus the baggage of high art prejudice. Only time will determine whether he gets the scholarly retrospective at a major Canadian public gallery he so justly deserves.

Dateline: 20 October 2007

ARTIST BEHIND THE MASK

At the Crease shows a masked hockey goalie crouched down in anticipation of an opponent streaking down on him on a breakaway or penalty shot — there were no shoot-outs when the painting was completed in 1972.

It’s a compelling image of high existential anxiety that sends viewers to the edge of their seats.

Some have suggested the painting is of Ken Dryden, the Hall of Fame goalie-turned writer-turned politician who played between the pipes for the famed Montreal Canadiens in the 1970s. Danby always denied that the goalie is Dryden, affirming instead that he ‘had not intended to represent any particular player… but simply the personification of a goalie.’ Undoubtedly that’s why it’s impossible to identify a team from the sweater, even though it bears a slight resemblance to the Chicago Black Hawks.

A story in the Guelph Mercury following the artist’s death identified the mystery player as Randy Kemp, who when Danby conceived the painting was a goalie for the Guelph Biltmore Mad Hatters.

I concede the goalie’s identity solves a mystery, satisfying what had been an provocative curiosity. But, in so doing, it kills the cat — and I don’t mean Emile ‘The Cat’ Francis a former goalie for the New York Rangers.

The model’s identity has no bearing on the image’s power to evoke tension and anticipation. Like scoring a goal or making a save, execution is everything in art. Many commentators have speculated about what the image of the anonymous goalie means metaphorically or even mythically. Danby would be amused by the hyperbole, without discounting its manifold possibilities.

Any image that excites the imagination and appeals to the emotions carries multiple associations — conscious and unconscious, overt and subliminal, literal and symbolic. This aspect of Danby’s work has been too often ignored by critics; meanwhile ordinary viewers intuit something happening between the lines of the artist’s work.

Despite all the ink that has been spilled on the subject, I’d like to dip my pen in the well.

The image is iconic because it says something essential about Canada. The significance of hockey to our collective imagination is too self-evident to be disputed or dismissed. Simply said, hockey is more than sport, recreation, pastime or business; it’s one of the things that defines who we are and what we are.

There’s no more dramatic contest in sports than a single opponent bearing down on a single goalie. To reflect the elemental nature of this contest, Danby eliminates every extraneous detail to create an image of stunning simplicity, producing an electrifying tension.

He draws us into the picture by making each individual viewer the puck handler/shooter. We become active participants rather than remaining passive observers. The anticipation of the thrill of victory or the agony of defeat is ours and ours alone, frozen in time as the buzzer winds down to the last remaining second of a game played on frozen water.

Danby, the Northern Ontario kid who grew up playing hockey and played it well into adulthood, felt the sport in the marrow of his bones. In his last years he completed many paintings of the North, including a homage to Tom Thomson, who, like Danby, died in Algonquin Park.

For my money, At the Crease is comparable to Thomson’s The West Wind or The Jack Pine. I know some will interpret this assertion as heresy. All members of the Group of Seven painted pictures of solitary trees struggling heroically against the natural elements, as did Danby (The Summer Sun and Summer Solstice). His singular genius lies in giving shape and expression to the same indomitable spirit — the raw, rugged essence of Canada — through a solitary goalie (who guards the net for thee).

In this regard, At the Crease possesses the same haunting mystique and visual power as Alex Colville’s Horse and Train, another iconic national image. It’s also a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. What James Joyce’s book means to the Irish imagination, At the Crease means to the Canadian imagination.

Danby sees artists as goalies — at least metaphorically. Both require talent and skill, especially acute hand-eye coordination. Both require an intensity of desire exceeding compulsion, verging on obsession. Goalies and artists are tempered in the heat of stress and pressure. Consequently, both see the world differently from the rest of us. I know because my son’s a goalie.

When artists create enduring work, they are like goalies making a save; when artists create forgettable work, they are like goalies who let the puck in the net.

I’ll skate a stride further. At the Crease is a self-portrait. It’s not a conventional self-portrait, but a portrait in a deeper sense because it tells us something fundamental about the artist. Danby sustained pucks of derision and dismissal fired by critics who could not see beyond subject and form to appraise theme and content. He stood his ground, at the top of the crease, covered the angles, protected the five-hole and kept his glove-hand high. Jacques Plante or Terry Sawchuck, Patrick Roy or Martin Brodeur have nothing on Ken Danby.

All of which makes At the Crease the most compelling sports picture painted by a Canadian artist in the 20th century — perhaps even in the history of Canadian art. It’s no wonder more than 100,000 copies of the image have been sold in Canada alone since Danby completed the original painting!

Dateline: 25 September 2007

PAINTING THE SOUL OF CANADA

News of Ken Danby’s death Sunday while canoeing in Algonquin Park is shocking.

At 67, he seemed a model of robust health. Still handsome, he enjoyed pickup hockey and squash as well as such physical activities in nature as canoeing, which he celebrated through his drawings, paintings, watercolours and prints.

As an artist, Danby was too successful for his own good. He defied the tastemakers of high art who disdained realism, by gaining fame and wealth outside the hierarchy of public galleries and academic study, even though his work is in permanent collections at the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre and the University of Guelph, as well as Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

Danby was steadfastly a realist at a time when the genre was dismissed as serious art in favour of abstraction and a wide range of ‘ism’ including conceptualism, formalism, postmodernism and deconstructionism.

Neither as rigorously formalist as Christopher Pratt, nor as hauntingly ambiguous as Alex Colville, Danby’s realism was accessible to people who knew little, and cared less, about contemporary fashion

In some respects, he was the Canadian equivalent of popular American realist Andrew Wyeth. He staunchly remained a landscape painter when the subject was disparaged as a legitimate subject for serious art. (It has since reacquired legitimacy.)

Danby’s approach to marketing alienated him further from the fine art establishment. Although he made limited edition silkscreen prints, many of his images were mechanically reproduced in large-volume poster format. His images adorned calendars and plates, not to mention such household items as wastepaper baskets.

The sheer ubiquitousness of some of his images — At the Crease, for example — tended to turn them into banal visual cliches. In this respect, he shared much in common with Canadian wildlife artist Robert Bateman.

Danby remained both defiant and unapologetic. However, you couldn’t talk to him long without it becoming clear he resented the neglect he received from art critics and scholars, even though he had his champions. Respected Canadian art historian Paul Duval wrote the text for a couple of books devoted to Danby’s early art.

A point can be made that Danby was unduly denigrated by the fine art establishment. He mastered the temperamental technical demands of egg tempera, in addition to unforgiving watercolour and oil. Like Canadian songwriter Gordon Lightfoot, whom Danby knew and commemorated in paint, he gave iconic expression to Canada, both its landscape and its people. Like Bobby Orr and Wayne Gretzky, other artistic subjects, Danby embodied and reflected the Canadian spirit.

Following in the brushstrokes of the Group of Seven, Danby painted the Canadian Shield — including Algonquin Park, Georgian Bay, Lake Superior and Algoma — which he first experienced growing up in Sault Ste. Marie. You could take the artist out of the North, but you couldn’t take the North out of the artist.

He painted the majesty of the Canadian Rockies and Niagara Falls, as well as southern England, Tuscany and the Caribbean where he vacationed. But no landscape was closer to his heart than the landscape around his home, a beautifully renovated 19th century mill located just outside of Guelph. The Grand River and Elora Gorge remained recurrent images.

Danby had no interest in mounting the pedestal of high art. He happily accepted a commission to produce images of Canadian Olympic athletes. He did projects for the United Way and Canadian Diabetes Associations. He served on the boards of the National Gallery of Canada and Canada Council. He answered a request from his childhood friend Gary Buck to paint portraits for the fledgling Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame.

Danby remained an engaged resident in the larger community. He was celebrated in his hometown and he was embraced by Guelph. He once led a local crusade against a landfill site. He was the recipient of the Order of Canada, Order of Ontario and Queen’s Jubilee Medal.

Like many a good Canadian, Danby loved hockey and paid tribute to the sport through portraits of some of the greats including Gordie Howe, Bobby Orr and Wayne Gretzky. But it’s images of unnamed hockey players — protecting the crease, facing off at centre ice, lacing up skates or kids playing shinny on ponds — that capture the sprit of Canada’s national pastime.

I talked to Danby a number of times. I visited his home, soaking up its pastoral splendour. I visited his studio, bustling with assistants working like bees in response to the commercial demands of his art.

Danby was always a gentleman. Personable, with a sense of humour, he answered questions with thought and care. He didn’t put on airs; however, he had the confident demeanour of the successful man. He was a serious artist and he was serious when discussing art.

Dateline: 2 November 2004

LAND, WATER & LIGHT

The title of Ken Danby’s latest exhibition is simple enough: Land, Water & Light: Ken Danby Landscapes. But its simplicity points to something more complex.

Landscape has been a dominant feature of Danby’s art from the beginning. Even when he explored other subjects and themes, he never abandoned landscape — even when contemporary landscape painting was dismissed by critics.

It didn’t help that Danby was an unapologetic realist painter at a time when realism was held in low regard by the tastemakers of high art. Confident and defiant, Danby always stuck to his brushes irrespective of what the critics said. His reward has been the financial success that accompanies popularity with the public and collectors.

Admittedly, the ubiquitousness of Danby images on everything from calendars and posters to plates and wastepaper baskets hasn’t endeared him to high art arbiters, even though it hasn’t hurt Van Gogh, Monet, Munch or Picasso, not to mention Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. ‘Critics come at my work from the wrong direction,’ he asserts while guiding me around the exhibition. ‘They can’t get beyond superficial responses to the images, which are representational. There’s more going on in my work than meets the superficial eye.’

The 51 recent landscape paintings on view at Toronto’s Joseph D. Carrier Art Gallery are more a refocusing and reappraisal than a departure for Danby. A little biography puts the new work in context.

Danby was born and raised in Sault Ste. Marie. Although he returned home regularly, the landscape of northern Ontario remained curiously absent from his art, in contrast to the landscapes of southern Ontario and the Caribbean where he and his wife vacation.

He began reassessing the landscape of his youth when he returned to ‘the Soo’ in 1994 when his father died. ‘The result of that experience renewed my interest in my roots which included the landscape,’ he explains. He suspects his reservations about depicting the North is connected to the tradition established by the Group of Seven and others. ‘It’s been done by so many artists, I didn’t think I had anything to add visually. Anyway, we all take for granted what is in our own backyard.’

Whether the result of experience, maturity or even his father’s death, Danby in recent years reconsidered his longstanding resistance. ‘I discovered I was seeing the Northern landscape with new eyes. I wasn’t repeating myself or relying on familiar mannerisms. I became excited and wanted to explore the imagery in more depth.’ Interestingly, a number of paintings (The Summer Sun, Summer Solstice, Windswept) recall the theme of the lone tree in Canadian landscape art.

His renewed interest in the North coincided with his designation as a Champion of the Great Lakes Heritage Coast, one of many public honours bestowed on Danby. ‘I thought I should begin looking more closely at the Great Lakes. I made many trips to Georgian Bay and Lake Superior, both on land and on the water.’

Danby describes the works in the exhibition as ‘a record of my direct and immediate responses to the landscape I encountered.’ They are not visual reflections of what he actually saw, he insists, but created images. ‘They are not photographic images. They are visual revelations that result from a process of absorption and distillation with the objective of making images more meaningful for viewers.’

Danby’s renewed interest in the landscape of Northern Ontario ‘spilled over to my travels elsewhere’ including Lake Louise and the Canadian Rockies (which also attracted some of the members of the Group of Seven), in addition to southern England and Tuscany.

In a number of oil paintings, watercolours and studies, he tackles one of Canada’s iconic landscapes, anchored by the exhibition’s centrepiece: Lake Louise. It take nerve to tackle such a well-known image. That he makes it his his own is testament to his technical skills.

Danby predicts he isn’t through with landscapes. ‘I expect to continue, perhaps in a much more emphatic fashion.’

Viewers familiar with Danby’s work will be surprised that 26 of the paintings are oil rather than his signature egg tempera. The exhibition has only one egg tempera, in addition to two serigraphs and 22 watercolours and studies. ‘I haven’t abandoned egg tempera,’ he confirms. ‘It’s just that the subject and the size of many of the works lent themselves to oil.’

Dateline: 2 November 2002

INTIMATIONS OF SPIRITUALITY

Ken Danby was recently named both to the Order of Canada and the Order of Ontario. To celebrate the artist’s appointments, not to mention his contribution to Canadian art, the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre is presenting an exhibition of 18 works.

The egg tempera and oil paintings, pencil drawing and digital print are drawn from the permanent collections of both the art centre and the University of Guelph, augmented by works from the artist’s studio. Although modest in size, the exhibition is not without interest, even for those familiar with Danby’s work.

First, it showcases a new acquisition for the centre’s permanent collection. Rainbow Study is one of two watercolours Danby completed in preparation of Niagara, a large oil painting of the Canadian Falls. The studies were done so he could determine whether to include a rainbow over the falls — which he eventually incorporated in the major work. Since the oil was unavailable, Danby produced a digital print especially for the exhibition.

The fact that Danby decided the rainbow was essential raises the question of whether his work can be interpreted within a spiritual framework. Such a question might be disconcerting to an artist more comfortable discussing hockey than religion. However, the works on view raise the possibility of being animated by a spiritual impulse.

Of course rainbows are a natural phenomenon that can be scientifically explained. They also comprise a theme in the tradition of 19th century sublime landscape art. The inclusion of a rainbow might well be justified for formal or aesthetic reasons.

Rainbows, however, have long been interpreted as religious imagery with their accompanying metaphorical and symbolic associations. And, when viewed in the context of other works in the exhibition, a strong sense emerges of what, for lack of a better term, can be acknowledged as spiritual.

Because Danby is a realist who paints recognizable images, his technical skills have gone under-appreciated. However, close examination of the works reveals both a heightened sense of, and an intensified contact with, reality. Such focused attentiveness is a component of a spiritual attitude.

Look closely at the waterfalls in Niagara, the trunks in Within the Willow, the vegetation in Spirit Seeker and The Offering, the water in The Fisherman and Cooling Off or the grass and large stones in Autumn Equinox. This is more than facility with the material qualities and the surface textures of the natural world. This is more than painting for painting’s sake.

Similarly, consider the central images of many of his works. Note how the youngster in Guelph Carousel, looks off to the side, away from both artist and viewer. At what or at whom is his concentrated stare directed?

Note how the sense of depth beyond surface appearance is conveyed in Cooling Off, which shows the bottom part of a youngster sitting on a rock with feet dangling in a pool of water.

Note how the serene reverence of the woman in Offering (a suggestive title) is conveyed as she conducts a ritualistic offering, an integral part of daily life on the tropical island of Bali.

Then there’s the tranquil, but intense, expression on the naked woman, with her back to both artist and viewer. as she gazes into the water in Spirit Seeker (another suggestive title).

And then there’s Autumn Equinox. While it’s generally believed the ancient monument of Stonehenge has something to do with astronomical observation, it’s clearly an aspect of pagan spirituality related to the cycles of the season. The sense of reverence and awe as embodied and reflected in the natural world and human experience — a feeling long associated with spirituality — is powerfully conveyed in the painting.

Dateline: 22 November 1998

KEN DANBY DOING IT HIS WAY

The signature painting in Ken Danby’s first Canadian exhibition of new work in 15 years says it all.

Titled Reflecting, the life-size portrait shows the artist at his easel. He stands looking directly at the viewer, intense but not aggressive. His right hand is reaching out to the viewer, but not in a gesture of measurement or assessment.

The artist is younger — some might say in his prime — since Danby started the portrait a decade ago when he was 48. The visual ambiguity is intentional in a picture full of ambiguity. Although there is nothing in the picture to tip off the viewer, the subject appears to be extending his left hand, the result of it being a mirror image.

The easel, which runs down the left side of the painting, was not added until recently, a seemingly small detail which, nonetheless, is significant because it places the artist in the tradition of artist self-portrait dating back at least as far as the Renaissance.

The picture is a compelling reflection of how Danby sees himself — an artist beyond mid-career but nowhere near retirement. Confident but not cocky, assured but not boastful, it’s an image of an artist who knows what he’s about, has nothing to prove, but still has things to reveal.

The painting is one of 89 egg temperas, oils, watercolours, prints and drawings on view at Toronto’s Joseph D. Carrier Art Gallery. The works span a decade, from 1988 through 1998. Most, though, were completed within the last year. The main exhibition consists of 67 works, with the addition of a dozen prints from a limited edition folio, titled Spirit of Canada, unveiled for the first time.

As some people muse about whatever happened to the guy who painted the masked goalie (At the Crease), Danby is overseeing his biggest exhibition of new work ever. ‘I’ve been distracted in recent years, but I began to feel it was time for an exhibition,’ The artist explains during an interview at his pastoral home/studio nestled on the banks of the Speed River.

It’s not that Danby has been idling away his time or resting on his laurels for the past 13 years. He completed various commissions, including a 1993 portrayit of hockey great Bobby Orr, and special projects for the United Way and Canadian Diabetes Association. He also served on the boards of the National Gallery of Canada and Canada Council.

In addition, he spearheaded a campaign that defeated a proposal by Wellington County and the City of Guelph to establish a landfill site in the vicinity of his beautiful country estate. The area was designated a UNESCO world heritage site before the local initiative to build a garbage dump.

A man who proudly paints to the rhythms of his own brush, Danby has never felt at home in the Canadian art establishment. He has steadfastly remained a realist, after a brief flirtation with abstraction as an aspiring artist, at a time when the arbiters of high art scorned realism. Consequently, he has maintained a position on the public gallery hierarchy higher than wildlife artists Robert Bateman and Glen Loates and below magic realists Alex Colville and Christopher Pratt.

To exacerbate debate, Danby has been successful from a commercial standpoint, remaining popular with the public and collectors. At the Crease, for instance, has achieved the status of national icon accorded American realist painter Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World. Moreover, the sale of reproductions of his images in various media has secured him a more than comfortable living.

Danby shrugs off criticism. (even though one gets the feeling it pisses him off, nonetheless.) ‘I have my audience,’ he asserts with a tone that implies critics be damned.

One of the rewards of a successful career is his ability to produce his own exhibition, dispensing with dealers and commercial galleries — and their 40-50 per cent commissions. Acting as his own agent, he has meticulously planned every aspect of the exhibition including placement of pictures using a scale model of the tony Carrier Gallery. ‘I don’t have any complaints with the dealers I’ve been involved with,’ he affirms, ‘I just wanted to be in full control of the decision-making.’

Many people inaccurately limit Danby’s work to sports images. In fact, he has always painted people and places that appeal to his imagination, including family and friends and the landscape around the home he has occupied since 1967.

Although he refuses to discuss details concerning the work comprising his latest exhibition, he concedes it reflects more of the interior artist than ever before. ‘Maybe it’s the result of age, but there is more of my inner vision in the work,’ he offers with a mischievous grin. ‘What you see is what I am.’ He expects people to be ‘intrigued and surprised’ by the work. ‘I’ve broadened my horizons.’

For his part, Danby’s expectations are high — he wouldn’t accept anything less of himself. ‘I think I’m showing important work,’ he declares without false humility. ’Nothing in the show is compromised.’

Below is a YouTube segment of Ken Danby — witty, passionate, insightful, engaging, advertorial — talking about his art at ideaCity05 (Uploaded on Jan 12, 2010):