Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout those days of mystery devoted to aspects of the painter’s life, art and legacy. The third instalment in the series is an appraisal of Jim Betts’ Colours in the Storm, the most enduring theatrical work devoted Thomson.

(Tom) blazed a trail where others may follow and we will never go back to the old days again.

— A.Y. Jackson

Tom Thomson went missing on July 8, 1917. Eight days later his decomposing body was found floating in Algonquin Park’s Canoe Lake.

Fishing line was wrapped around an ankle; he had a four-inch bruise on his temple and traces of blood in one ear. Although the coroner subsequently ruled death by drowning, there was no water in his lungs. Strange.

His death ignited the mystery that fuelled the legend surrounding Canada’s best known — and most notorious — artist. Suspicions swirling amid rumour, gossip and innuendo linger regarding his death. Was it an accidental mishap? Did he stumble while standing in his canoe to pee (it happens more often than you think)? Was it misadventure or foul play — whether manslaughter or even murder? Was it suicide?

Controversy and debate linger about where Thomson’s remains are buried — in Leith cemetery outside of Owen Sound, where he was raised, or in a secluded cemetery in the park (his spiritual home) not far from Canoe Lake, where he was initially interred.

And to think, he didn’t begin painting seriously — where his true stature rests — until he was 34 years of age, a mere five years before he died.

To acknowledge the centenary of Thomson’s death, London Ontario’s Grand Theatre is presenting Colours in the Storm, a musical with book, music and lyrics by Jim Betts.

Colours in the Storm is one of numerous musical and theatrical works produced about the artist over the last quarter century. Although it’s called a musical as a convenience, it’s more a drama of adventure, romance and intrigue against a musical backdrop, punctuated with memorable song.

The play traces Thomson’s life from his first trip to Algonquin Park in 1912, through his remarkable development as a painter profoundly influenced by the landscape of the Canadian Shield. It presents the small, isolated, enclosed community the artist encountered and outlines the tensions, both romantic and hostile, that emerged. Finally, it speculates about what might have happened on that fateful July in 1917 — without advancing any conclusions. The mystery remains.

Although Betts covers all the familiar biographical markers, his play doesn’t become pedantic because his focus remains on how a man becomes the artist he was destined to be by transforming the light and colour he experienced first-hand into iconic images that become enduring symbols of the soul of Canada — the Mystic North.

Colours in the Storm has gone through several revisions since premiering at the Muskoka Festival in 1990. I have seen it four times now — and remain eager to see it many more times.

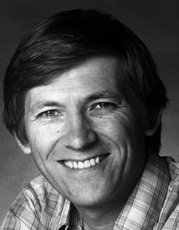

I was captivated by the play the first performance I attended in 1994 when Tapestry Theatre brought a touring production to the University of Waterloo’s Humanities Theatre. It was directed by Richard Greenblatt and starred Michael McManus as Tom. I saw another production — I think it was at Guelph’s River Run Centre — starring Jonathan Whittaker as Tom. (Whittaker created the role in the inaugural production.) I also saw a reworked production at Theatre Orangeville in 1997.

As one would expect, each production casts a slightly different light on Thomson. This production is no exception. Directed by Heather Davies, with musical direction by Marek Norman, it’s noteworthy for its focus on Thomson’s creative struggle to give artistic expression to his intense sensory impressions and the powerful emotions they evoke.

Veteran designer Shawn Kerwin’s set serves this goal effectively and efficiently. It’s minimalist, consisting of a couple of large, revolving slabs of rock, one of which acts as a canoe — believe it or not.

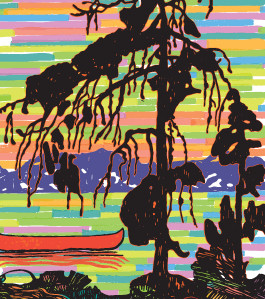

The backdrop is bare sky with the exception of one cumulus cloud that magically transforms before our eyes — thanks to Rory Leydier’s projection design — into Northern River, one of Thomson’s great paintings and the inspiration for the play’s signature song.

Anyone familiar with Algonquin Park might question the lack of trees in the set, but my theatre companion Lois suggested, rightly I think, that it was intended so as not to compete with Thomson’s iconic paintings of trees (The Jack Pine and The West Wind, the latter of which is also commemorated in song).

I’ve always enjoyed Bett’s songs, which have aged well like fine malt whisky. They evocatively mirror both the external landscape and the interior landscape of the artist’s mind and emotions. The score is indebted to traditional folk and Celtic traditions, perfect for a small acoustic ensemble.

For the most part the play unfolds naturalistically and chronologically. But in a work that explores the mysteries of the creative imagination, one might expect to hike down the path less traveled where dreams and visions, ghosts and wild people take refuge.

The cast takes the notion of ensemble acting to heart with Jay Davis as Tom, Ma-Anne Dionisio as Tom’s romantic interest Winnie Trainor and J.D. Nicholsen as Tom’s patron Dr. James McCallum.

The remaining cast members assume multiple roles including: Binaeshee-Quae Couchie-Nabigon as Wild Mary/Annie Fraser; Gab Desmond as Mowat Lodge proprietor and murder suspect Shannon Fraser/Group of Seven member Lawren Harris; Michael Dufays as local guide Larry Dixon/Hugh Trainor; Tim Funnell as murder suspect Martin Fletcher/park ranger Mark Robinson; Seana-Lee Wood as Marie Trainor/Frances McGillivary.

I would consider Davis more actor than singer, but Dionisio steals the spotlight with her wondrous voice. The ensemble harmony is especially fine.

Jessica Poirier-Chang’s period costumes are right on the mark. The creative team is rounded out with lighting designer Renee Brode and sound designer Jim Neil.

I’m grateful to the Grand, which pulses at the artistic heart of my hometown, for presenting Colours in the Storm, one of our most enduring homegrown musicals. I hope other theatres across the country take note and follow suit during this special centenary in the history of Canadian art.

Colours in the Storm

Grand Theatre

Information and tickets at 519-672-8800

or online at grandtheatre.com