Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day throughout these days of mystery devoted to the painter’s life, art and legacy. The seventh instalment, How Tom Thomson Found Me, is a personal account of how I discovered Thomson and the Group of Seven and how the artists shaped me life.

Canadians have been searching for Tom Thomson since he died shrouded in a mist of mystery in July, 1917. This is the story of how the legendary painter found me.

Making the connection between influences that determine the shape of someone’s life is not a simile, but a metaphor or even a symbol. To paraphrase the late, great Willie P. Bennett, I was one of the Lucky Ones. My vocation as a newspaper reporter over four decades, three of which were spent covering the arts, was a professional manifestation of my avocation. I earned a good living writing about my passions: books, theatre, music, visual arts, even fly fishing.

My journalistic career began taking nebulous shape in high school, but the lines were sketched in elementary school unbeknown to me. That is where the story of Thomson finding me begins.

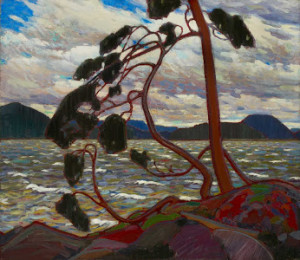

Thomson and the Group of Seven — or rather works by the legendary painters — first infiltrated my consciousness through framed reproductions mounted in the classrooms of one of the public schools I attended in London, Ontario in the 1950s and ’60s.

Although I’m remembering back half a century, I recall not knowing what to make of these curious pictures. I can’t say I liked them. They didn’t resemble any of the landscapes with which I was familiar through illustrated books and television programs. It didn’t help that I had never set foot inside a gallery; consequently, I didn’t know how they compared to other works in the long and winding history of art.

I didn’t begin to understand Thomson and the famous group that formed in 1920 intellectually until I studied Canadian literature at university in the ’70s. My passion for homegrown literature led naturally to a fascination with Canadian theatre and visual art. My interest in Canadian music had already been triggered by my Grade 10 English teacher who introduced me to Leonard Cohen. It was about the time I discovered Gordon Lightfoot, who became an enduring personal hero. I bought a guitar in emulation of the folk legend and immediately set about learning his songbook.

I developed an emotional appreciation of Thomson and the Group when I began traveling to the Canadian Shield, first in Muskoka and later in Algonquin, Algoma and North of Superior. Images that perplexed me in elementary school gradually made sense.

I was one of the Lucky Ones as a youngster. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know Billy, my closest childhood friend. He was an only child; his dad was a firefighter, as was mine. He lived around the corner from me. We shared some of the same classes in elementary school. We were inseparable until I moved to another part of the city. We subsequently attended different high schools. I went off to college and then university; he went to work. Our worlds gradually parted.

Billy was like a brother and his mom and dad were surrogate parents. One of the benefits of friendship was traveling with them. They introduced me to camping and to fishing, the latter of which remains a passion. I joined them on a car trip ‘Out West’ to British Columbia when I was 10 years old. It was my one great childhood summer adventure. It was eye-opening to see Northern Ontario, the Prairies and the Rockies first-hand.

The most lasting gift, however, was accompanying Billy and his parents on visits to his Uncle Fred (his mom’s favourite brother) and Aunt Pat. They lived on a farm outside of South River, a village ‘in the foothills of the Laurentians, 32 miles south of North Bay,’ as we described it then and as I describe it now. We referred to our visits, which spanned the four seasons, simply as ‘Goin’ Up North.’

Talk about adventure. We left school at noon on the Thursday or Friday of a long weekend, whether Easter, Victoria Day or Thanksgiving. We spent longer periods visiting over Christmas, March break and during the summer. (I was thrilled to learn that Thomson was not only familiar with South River, but would have passed through the village numerous times. He even stayed at the New Queen’s Hotel in the village.)

The six-hour drive in hospitable weather grew more exciting when we left the four-lanes of the 401 and 400 and traveled the two-lane Hwy 11 (which, of course, is now a minimum of four lanes). The towns we passed had the allure of place names on a treasure map: Barrie, Orillia, Gravenhurst, Bracebridge, Huntsville, Sunridge. Despite what official maps indicated, these were northern towns in a northern land.

We always stopped for a late supper at the Girls’ Truck Diner, a truck stop festooned with stuffed animals from the Canadian wilds: beaver, otter, martin, snowshoe and cottontail rabbit, mink, skunk, raccoon, weasel, muskrat, porcupine, lynx and wolf— you name it. Outside there were a couple of forlorn bears in a cage salivating over whatever scraps were tossed their way — a sad thought today, but exciting as hell for a boy who slept with his BB gun beside his bed and thought fishing was surpassed only by hockey.

Best of all were Billy’s Uncle Fred and Aunt Pat, who served as a feast for a boy’s voracious imagination. They were figures of romance and adventure, who lived by the needle of their own compass — which always pointed true north.

Although it was the ’60s, visiting Aunt Pat and Uncle Fred was akin to folding back the blankets of time and crawling under the sheets of bygone pioneer days. They subsisted on 400 acres of marginal land — most of which was bush — not far from the south-west boundary of Algonquin Park. They had neither electricity nor indoor plumbing. They cooked and heated by wood.

I remember Aunt Pat as a robust redhead, freckled with a broad smile as bright as polished ivory keys on a piano, which she played with graceful, infectious enthusiasm. Yes, she had a temper, but it burned out quicker than it ignited. She augmented Uncle Fred’s meagre disability pension by driving school bus. Every Christmas she made Billy and me flannel pajamas, stitched on a meticulously maintained, manual sewing machine.

Uncle Fred was a small, wiry man, tough as binder twine. His eyebrows resembled fat caterpillars perched above gentle eyes of robin’s egg blue — one of which was blind. He had lost his left leg at the knee to an errant 40-tonne log. The index finger on his right hand, severed at the second knuckle, didn’t prevent him from rolling his own cigarettes. One was glued to the side of his toothless mouth from sunrise to bedtime. In the summer he wore white shirts — rolled up to the elbows — to discourage ever-present black flies. He had names for the dozen head of cattle he raised and identified by their bells.

He bled Maple Leafs blue and kneaded raw contempt of the Canadiens. His devotion to the federal Conservatives, heroic enemies of the despised Liberals, was steadfast. Despite his physical blemishes, he was a curiously handsome man, with a gentle disposition as durable as hickory.

Uncle Fred’s eyes would moisten whenever he recalled having to put down King, one of his border collies years earlier, following a misunderstanding with an ornery porcupine. The bullet barely grazed Queenie and he didn’t have the heart to put another bullet in the chamber. So she lived a long life, with quills still deep in her throat, following close behind, wherever he went on the farm, whether limping on foot or behind the wheel of an ancient John Deere.

Meals were a grand occasion. The aromas that permeated the kitchen defy description. We ate homemade bread baked in the majestic woodstove — Uncle Fred continued baking bread well into his 80s, long after Aunt Pat died. We enjoyed pan-fried brook trout and breaded partridge, roasted venison and moose. I remember bear steaks. We also had such domesticated fare as roast beef with Yorkshire pudding; eggs collected daily and range-fed chicken, fresh vegetables from the garden or put up for winter; wild blueberries for mouthwatering pancakes and pies and preserves of all kinds. We drank throat-numbing, hard water from a hand pump.

I recall with mixed emotion the outhouse we frequented both summer and winter. In winter we negotiated a narrow path packed down with snowshoes because of snow that could be four- or five-feet deep. The two-holer would be rimmed with thick, hoary frost. During the long, cold winter nights, which could plunge as low as 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, we used what we euphemistically called a thunder jug, kept tucked under beds made cosy with thick layers of heavy blankets.

I remember going outside for a pee with Billy and Uncle Fred at night. Once during a chilly Thanksgiving weekend, Uncle Fred observed: ‘boys, look at that sky. You don’t see stars like that in the city.’ He was right. Another time he described the call of a distant whip-o-will as ‘lonesome’ — a more poetic word than lonely, as Hank Williams, a man familiar with heartache, knew. Uncle Fred called the stream where we fished for brook trout ‘the crick’ and he referred to ‘the bush’ rather than to ‘woods’ or ‘forest.’

What I remember most fondly was sitting around the kitchen table, bathed in the warm patina of Coleman lanterns and coal oil lamps, while the adults talked long into the night, recalling stories from the past. Some of these involved Uncle Fred and Aunt Pat eloping, the young couple heading West so he could operate a bulldozer on the Al-Can Highway, along the British Columbia interior into Alaska during the Second World War. She once shooed away a grizzly by wielding a frenzied broom — both sons still babies.

I learned much later they didn’t get married until Aunt Pat was on her death bed. They shared a full, rich life; however, they suffered more than their share of piercing sadness, including the loss of their sons to muscular dystrophy while they were in their early 20s.

I think you get the picture with respect to the world of wonders I entered when we visited Uncle Fred and Aunt Pat. But you must be asking: what do these recollections have to do with Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven? Everything.

The answer begins with what I experienced when Billy and I immersed ourselves in the bush:

• On long walks in search of beaver ponds or mysterious, long-abandoned shacks;

• Hunting partridge with our shotguns when we were older. A beautiful 12-gauge Winchester pump shotgun was one of my prized possessions, purchased with money saved from my first job as a bell hop at the Hotel London;

• Dapping (also known as dappling) for brookies with long bamboo poles purchased for a couple of dollars in a local hardware store;

• Helping Uncle Fred bring in chords of winter wood which he spent weeks cutting, all the while cussing his temperamental chainsaw;

• Just taking in the splendour of fall foliage or a thick snowfall or a silence so intense you could hear your heartbeat pulsing against your eardrums;

• Or simply playing as boys do: cowboys in the high country, explorers in uncharted territory, pioneers carving out a home in the New World or soldiers in harm’s way behind enemy lines.

Whatever the circumstances, I was embraced in the arms of the bush. When I entered the bush, really got inside, I perceived with my senses and apprehended through intuition what Thomson and the Group expressed through their paintings. I was enclosed and engulfed by what I came to acknowledge as Tom Thomson or Group of Seven Country.

I shared with the painters the same shock of recognition that came with acquainting myself with a hitherto unknown landscape. I experienced the same charge of imagination as the painters did — what the great literary critic Northrop Frye once referred to as ‘sympathetic imagination.’

This, even more than what I later learned, is why Thomson and the Group are interwoven with my growing awareness of the Canadian landscape — my own story. It’s why the painters exert such a tenacious grip on the national consciousness. There’s something elemental about their paintings that penetrates the soul of Canada as it pierces the inner depths of my own being. I believe this process is mythic in thrust.

This mythic process isn’t unique to me. Most people feel an affinity with artists who speak to them at a deep level. Canadian writers Al Purdy, Ernest Buckler, W.O. Mitchell, Alistair MacLeod and David Adams Richards and songwriters Stan Rogers, Willie P. Bennett and aforementioned Lightfoot affect me in ways comparable to Thomson and the Group. These authors and songwriters share with the painters a response to the spirit of place that transcends and transmutes locality. Their creative imaginations are grounded in the geography of the heart, as they are the history of the soul.

But there’s more on a prosaic level. The first art gallery I ever visited was the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg. The first art works I ever purchased were prints of work by Lawren Harris. When I worked for the Brantford Expositor before moving to the Waterloo Region Record in Kitchener, I wrote art columns arguing that Harris deserved more public recognition in the city of his birth. My bathroom brims with posters of Thomson exhibitions.

The lives, the art and the legacy of Thomson and the Group are interconnected with my love of the Canadian wilderness, especially as embodied and reflected in fly fishing. My appreciation of Thomson, most particularly, has grown as I’ve matured and learned more about Canadian culture — and as my fondness for fly angling blossomed into passion.

In four decades of newspaper work, most of which were spent as an arts reporter, I wrote about Thomson and the Group more than any other visual artists. I have in my personal library, and have read, more books about Thomson and the Group than any other artists. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to confess that I see the world of nature — not to mention Nature — through the brushstrokes of Thomson and the Group. And I’m not alone.

In years past, when I fished for bass with my two sons in a small boat on a small lake east of Peterborough, or more recently, when I wade alone or with companions in a river with fly rod in hand, I hear Thomson, a gifted fisherman as much as a gifted a painter, whispering in my ear. He’s a constant presence on the water.

Thomson would have been a much different painter had he not been a fisherman. The glorious colours in his paintings are the colours of brook trout, one of nature’s loveliest creations.

These personal reflections aside, Thomson and the Group of Seven form the bedrock of Canadian art. In the same way Ernest Hemingway declared that modern American literature begins with Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (I paraphrase), so too does modern Canadian art begin with Thomson and the Group.

Their place at the head table of Canadian art is assured. You can no more discuss Canadian art in the absence of Thomson and the Group than you can discuss American art without Abstract Expressionists, French art without Impressionists, German art without Expressionists, Russian art without Constructivists or Italian art without Futurists.

In a literary context, they’re comparable to the Transcendentalists of New England, the Romantic poets of England or, on a lower rung on the ladder, the Confederation Poets of Canada, in terms of representing the culmination of what went before and what followed.

Like ’em or loath ’em, you can’t leave ’em. Thomson and the Group can be neither ignored nor dismissed. Irrespective of the foreign styles that influenced them, including post-impressionism, Northern symbolism, Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau, they produced work — for the first time in our history — that can be acknowledged as singularly Canadian.

Moreover, their influence extends into the new millennium. The couple of generations that followed, especially English-Canadian artists such as the Regina 5 and Toronto 11, pitted themselves against Thomson and the Group in a Freudian struggle of artistic sons defining themselves by ritualistically killing their artistic fathers. Talk about the anxiety of influence.

In contrast, contemporary artists are less anxious, acknowledging the seminal role Thomson and the founding members (Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Frank Carmichael, Fred Varley, Frank Johnston, J.E.H. MacDonald and Arthur Lismer) and the later members (A.J. Casson, LeMoine FitzGerald and Edwin Holgate) played in the development of not only Canadian art, but Canadian culture.

The Group of Seven artists lingered in Canadian consciousness long after the group disbanded in 1933. Although all the founding members enjoyed solo careers, they could never shake their collective identity. We wouldn’t let them. Meanwhile, Thomson’s mysterious death ensures his survival beyond the grave as a folk hero of cultural legend.

The famous painters endure for a simple, yet powerful, reason: as long as there are lonely pines sculpted by westerly winds against a backdrop of rock and rippling lakes under dramatic skies, they will speak to every Canadian not wholly alienated from the land on which their country was built and endures — at least for now.