Wildlife art — love it or hate it. It’s black or white; there’s no grey on this paintbrush. The battle line is drawn in indelible ink — the high art pundits and connoisseurs on one side; the general public without specialized training on the other side.

It’s an art form that’s evaluated and judged through a narrow lens based on how a commentator interprets familiar images and recognizable content. In contrast to ‘legitimate’ art forms, no ground is given to intention or execution. To paraphrase Ms Stein, a bluejay is a bluejay is a bluejay.

In other contexts, this tunnel vision — perhaps myopia is the more accurate word — would be recognized for what it is: a bias, a prejudice.

Owen Sound’s Tom Thomson Art Gallery challenged cliché, preconception and stereotype in late 2010 when it organized and circulated an exhibition of work by George McLean, one of Canada’s most accomplished wildlife artists.

Virginia Eichhorn — director of The Tom and former curator of Waterloo’s Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery — curated the retrospective exhibition, titled George McLean: The Living Landscape, and contributed to the accompanying catalogue.

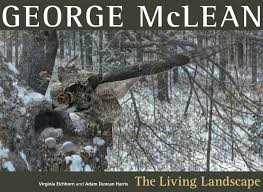

Published by Goose Lane Editions, the catalogue is a handsome, hard-bound, coffee-table book. Eichhorn contributes one of three critical essays. This Little Moment of Truth acts as an introduction and provides a thematic overview.

The very premise of the exhibition, not to mention the accompanying book, is audacious.

So-called wildlife art has yet to be accepted as a legitimate art form. As a result, artists such as McLean are relegated to the margins, dismissed and ignored, if not disdained and scorned. Not long ago, photography, ceramics and First Nations art battled for legitimacy. Happily, few would argue that the best of these art forms and visual traditions should not be accepted as fine art today.

It’s strange that while most styles of representational art — whether naturalism, realism, high realism or photorealism — have gained respectability, wildlife art remains on the sidelines of fine art exhibition and discourse. This can’t be because wildlife art is accessible. The aforementioned styles of representation are readily understood and appreciated on a superficial level, even if they embody and reflect more than they appear to convey.

It can’t be because wildlife art is popular with people who are not art experts. Artists from Michelangelo to Monet and Van Gogh, Picasso to Warhol, not to mention Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven, are popular with experts and public alike.

Similarly, it’s unreasonable to conclude that it’s because wildlife art lacks technical virtuosity, compositional appeal or conceptual rigour. The range of technical, compositional and conceptual accomplishment in this art form is comparable to the range of qualities found in other styles of representation.

The answer is obvious. The reason contemporary wildlife art is not viewed as fine art is subject matter. Arbiters of fine art concede it’s permissible to appreciate wildlife art within a historical context — whether John James Audubon, Winslow Homer, Frederic Remington, Alexander Pope or Paul Kane. But contemporary wildlife art is repudiated as unworthy and undeserving.

McLean has been painting animals and birds within the context of the landscape around his Grey County home for more than three decades. He’s gained a well-deserved reputation as one of Canada’s foremost wildlife artists.

The Living Landscape pushes the debate further. It formulates — courageously — that McLean deserves to be discussed in terms of contemporary Canadian art as a painter of aesthetic merit. Moreover, it cautions us not to paint all wildlife art with the same condescending brush, which camouflages intellectual bias and aesthetic prejudice.

There was a time, not so long ago, when the late Alex Colville remained an annoying burr in the sanctimonious rump of the high art establishment. But, as confirmed by a major retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2014, one of the most popular Canadian artists of the second half of the last century is undergoing a reappraisal.

American realist painter Andrew Wyeth underwent a comparable reassessment following his death.

It’s still too early to declare, but the late Ken Danby might well be on his way to a reappraisal based on a pair of concurrent exhibitions at the Art Gallery of Hamilton and Guelph Civic Museum.

The question remains with respect to McLean — did The Tom initiate a re-evaluation of an artist who does not fit the round ‘wildlife’ hole, at least as the phrase is generally understood? As in all matters artistic, time will have the last word.

Below George McLean speaks about his wildlife and landscape art at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection http://www.McMichael.com