Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I am posting a blog each day devoted to aspects of the painter’s life, art and legacy. The second instalment in the series is an appraisal of George A. Walker’s The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson, a wordless book that speaks volumes about the painter’s enduring spirit.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson is worth 109,000 words.

George A. Walker’s wonderful visual narrative chronicling the life and death of Canada’s most famous — or is it infamous? — artist consists of 109 woodblock engravings; so you do the math: 109 x 1,000 = 109,000.

After making my way carefully and attentively through the volume, akin to literary bushwhacking, that number of words seems about right to describe Walker’s wordless narrative.

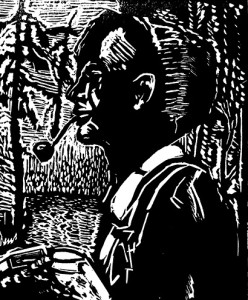

Not to be confused with Canadian playwright George F. Walker, George the Engraver is an award-winning artist, teacher, author, illustrator and publisher who has been producing artwork and books in his Toronto studio since 1984.

An associate professor of book arts and printmaking at what used to be the Ontario College of Art (now known as OCAD University of Toronto), Walker has illustrated handprinted limited editions written by Neil Gaiman, celebrated author of comic books, screenplays, fiction and song lyrics. He has also illustrated the first Canadian editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass.

But I’m interested in Walker primarily for his evocative telling/retelling of Tom Thomson’s Adventures in the Wonderland of Algonquin Park.

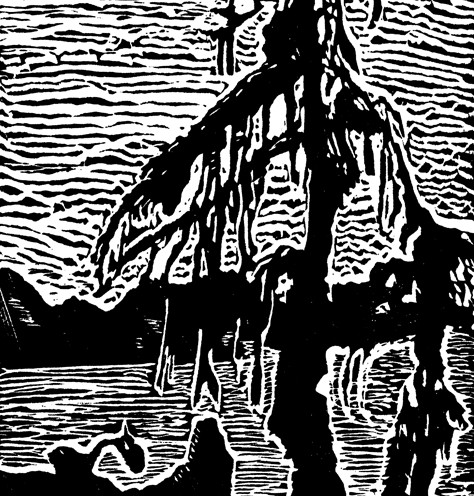

In contrast to such engravers as Wesley Bates and Gerard Brender à Brandis, Walker is carved from a different tree. Bates and Brender à Brandis engrave with a stylized elegance which is by turns fanciful and whimsical. In contrast, Walker’s engravings resemble images that have been hewn from maple, oak or walnut with sharp axes and large hunting knives.

Whereas Bates and Brender à Brandis reflect a pastoral artistic sensibility — think St. Lawrence Lowlands— Walker is thoroughly Canadian Shield, raw and rugged. Despite, or rather because of, their contrasting aesthetics (Bates and Brender à Brandis are distinct in their own right), I admire all three artists equally.

Published in 2012 by The Porcupine’s Quill, The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson traces the artist’s life from his rural youth outside Owen Sound to his death in July 1917 in Algonquin Park — his spiritual home and epicentre of his legacy — which continues to haunt the Canadian collective memory with the same potency as the so-called Black Donnellys of late 19th-century Lucan, Ontario. Nothing like violent death to arouse fevered imaginations.

In his engaging introduction, art historian/curator Tom Smart accurately describes the narrative as ‘a visual elegy reflecting on the loss of a gifted artist and a man of his time fluent in the visual language of modernism, who also found solace and an artistic muse in the wilds of the Canadian bush.’

Smart observes, again accurately, that the ‘wordless pictographic’ narrative ‘about finding redemption in death is ultimately about the meaning of remembrance, and is also a parable about artistic creation.’ I like the implied association between Walker’s images and the kinds of First Nations rock paintings found through the vast expanse of the Canadian Shield.

I would add that The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson is also about transformation generally and, specifically, about how artistic creation is a process of transformation: word into image, nature into art, art into myth.

Smart, once again accurately, asserts: ‘This is a narrative constructed around a man and his search for meaning by experiencing nature.’ I would argue that this is one of our defining national myths, spanning literature, drama and the visual arts.

The narrative is also a dialogue between two artists (with roots in graphic design and commercial art) who employ different media to bridge distances of time and place. Both artists are mythmakers. It’s no accident The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson was published 100 years after the artist made his first trip to Algonquin Park — a visit that changed his life, sealed his death, made him legendary and, in the process, along with the Group of Seven, defined how we see and relate to the Canadian wilderness.

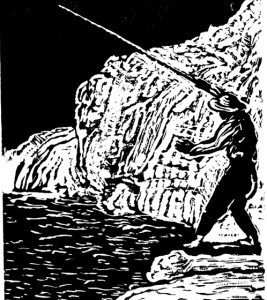

As an avid fly angler who is confident Thomson was both fly fisherman and bait fisherman, I’m pleased Walker pictures the artist as adept with fur and feather.

Many of Walker’s engravings will be recognizable to readers — yes, you do read the images — familiar with Thomson’s paintings and archival photographs associated with his life. Other images spring like a limestone creek fresh from Walker’s creative imagination.

I will leave it to readers to interpret Walker’s take on what led to Thomson’s death on Canoe Lake, at the age of 39 — interestingly, the same age that Welsh poet Dylan Thomas died, also resulting from complications connected to booze. Those familiar with the speculations surrounding Thomson’s death will not be surprised; however, the wordless narrative leaves space between the lines for further conjecture.

At bottom, Walker is a storyteller not only drawn to a well-known national story, but compelled to retell the story anew not in words, but in line, contour and shape — the same vocabulary his subject/artist/hero used to tell his story of the Canadian ‘wilderness’ and, in so doing, tell the story of Canada.

‘I will go to the country where the cedar is felled,’ the epic hero Gilgamesh tells his sidekick Enkidu (Smart reveals that Walker draws on the ancient tale as the foundation on which to build his story of Thomson). Following in the footsteps of the epic hero, Thomson and Walker venture separately, but together, into that country where cedars are felled. The proof is in Thomson’s paintings and in Walker’s engravings.

It would be fascinating to see what an animation filmmaker might do with The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson. I’m thinking of something along the lines of the British TV animation The Snowman — only for adults.