KITCHENER — I got to know Robert Achtemichuk when he was director of the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery.

Seldom have a I met an artist so acutely uncomfortable in the skin of an institutional administrator — a position he held at the Waterloo gallery from 2004 through 2010. Happily, he’s back doing what he was placed on earth to do — making art. (I make this observation modestly.)

I first reviewed a representative sample of Achtimechuk’s work with Outskirts, an exhibition of 37 small-scale, watercolour and gouache on paper and silk by the Kitchener artist. The works captured the emotional texture of the established, urban neighbourhood in which he lives.

Comprising works completed between 2004 through 2013, Outskirts was a continuation of paintings featured in a smaller exhibition in 2011. The paintings were produced by an artist intimately familiar with his inner-city neighbourhood: its streets, houses, rooftops, garages, backyards and alleyways. They were built up from perspectives seen from the artist’s backyard or from an upper window in his second-storey house.

All but a couple were nightscapes — when sunlight surrenders to darkness, the street lights come on and residents retreat indoors behind lighted windows. Darkness permeated the paintings, with the exception of windows, open doors and street lamps producing epiphanies of electric light. People were absent, but their presence was implied.

Brooding and atmospheric, the dreamy nocturnes followed a tradition associated with music (John Field, Frédéric Chopin, Erik Satie and Samuel Barber, among others), but equally applicable to poetry (the Romantics wrote such nocturnes as Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Frost at Midnight) and to visual art (J.M.W. Turner, James McNeill Whistler, Edward Hopper and, closer to home, Homer Watson).

Although impressionistic in style, the paintings referred to precise dates and exact times, as reflected in their titles. The paintings spanned the four seasons in all weather, but the majority were winter scenes, inhabited by black, skeletal trees under a canopy of moody clouds and a moon shivering in the night sky.

In a quiet, methodical way, Achtemichuk rendered the familiar unfamiliar and the ordinary extraordinary, as if reality were filtered through slightly refracted lenses.

Reflective and meditative, the paintings were secular prayers reminding us of the wonders that reveal themselves through the mundane and the everyday when we have eyes to see closely and attentively.

Viewers, who had strolled through a familiar neighbourhood after sunset and wondered about the lives of the people retired to their homes for the night, would have responded directly and immediately to the exhibition.

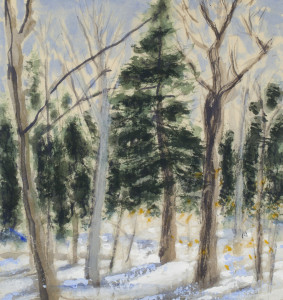

In Homer Watson’s Footsteps — one of three exhibitions on view at Homer Watson Gallery — might be viewed as a variation on complementary visual and emotional themes first explored in Outskirts.

Achtemichuk collected images of successive seasons in the woods near where Watson lived and painted in an effort to follow — literally — in Watson’s footsteps; locating the sites and painting the same scenes the earlier artist had painted. Spurred on my his love of mature trees, Achtemichuk made his way through the area where the Speed and Grand rivers meet, continuing down the Grand through Cambridge and Carolinian forest into Paris.

The artist didn’t find the old growth forest of Watson’s day, but trees that were seedlings when the earlier artist lived in the house at Doon, which became the Homer Watson Gallery.

Superficially, this is a tribute by a contemporary artist to an artist from an earlier era. It’s also an acknowledgement of the landscape that inspired the majority of the earlier artist’s oeuvre, which continues to inspire the contemporary artist.

But it is more than a simple and direct response. In Homer Watson’s Footsteps is a conversation, a dialogue, an intimate exchange between two artists who shared/share the same geography, but transcend the limitations of time. In other words, a visual dialectic with the implied message: this landscape of river and adjacent woods must be preserved, must be saved, must be appreciated, must be cherished.

The area began to change from a pastoral/rural landscape to an urban/industrial landscape during Watson’s later years — a transition reflected in his last works. The transformation continues under Achtemichuk’s attentive and sympathetic eye.

As with Outskirts, the 14 watercolours on Japanese Washi paper comprising In Homer Watson’s Footsteps are precisely dated and timed. Completed between September 2014 and May 2015, they were mostly executed in early afternoon. The brushwork is loosely impressionistic, implying they were done quite rapidly. Trees and the river itself dominate, although there are occasional references to other associated details.

Again, as with the earlier series, the watercolours are atmospheric tone-poems written in line, shape and colour.

With Unmanicured, fellow Kitchener artist Joe Fancher provides a different perspective on the same general area Achtemichuk celebrates through visual expression.

Fansher’s view, however, is even more modest, more detailed, as if viewed through micro lenses. With pencil, pen and watercolour brush, he isolates and concentrates on small elements (flowers, weeds, branches, twigs) of the complex chaos of nature. His delicately rendered drawings and mixed media paintings combine simplicity with attention to detail.

Fansher invites casual viewers of the natural world to stop and look attentively — really look — into the wonders contained in, and revealed to, the careful, sympathetic eye. This is as much a contemplative act as an act of seeing. This is meditative vision — what the English poet William Blake referred to in Auguries of Innocence as seeing ‘a World in a Grain of Sand and a Heaven in a Wild Flower.’

The Homer Watson Gallery has been presenting annual memorial exhibitions devoted to its namesake for a quarter century. This summer’s anniversary exhibition, Interconnected: A Journey through time, is especially noteworthy because it features some works that will be coming up for auction.

The exhibition features 16 paintings spanning Watson’s career, from the early classically influenced The Isle of Man (1873) through such works as The Gravel Pit and The Shack in the Pit, completed in the 1920s and 30s that reflect a landscape in dramatic transition.

Gallery executive director Faith Hieblinger notes that in later works Watson turned increasingly to winter, as well as to the threshold hours of dusk, when sunlight succumbs to darkness (which the Celts called the gloaming) — metaphors perhaps of mutability and mortality.

The works are from the Don and Dorothy Engel Estate Collection. The local collectors often loaned works to the gallery anonymously. Hieblinger notes that the late Don Engel’s three decades of collecting traced Watson’s maturity, establishing a parallel chronological arc between artist and patron.

When viewed as a whole, these three complementary exhibitions comprise a parallel journey through art, through life, linking past and present and anticipating a future, revealing both the life of nature and the nature of life.

In Homer Watson’s Footsteps, Unmanicured and Interconnected: A Journey Through Time continue through Aug. 16 at the HomerWatson Gallery. Information and gallery hours are available at 519-748-4377 or online at www.homerwatson.on.ca

(featured image is cropped version of Homer Watson’s Untitled: Winter at Dusk)