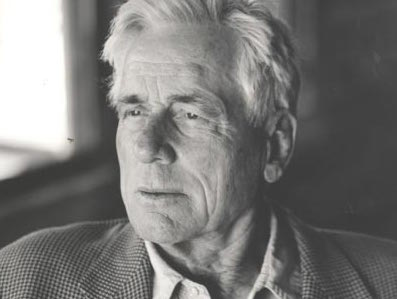

Thomas McGuane is better known more for the raucous life he once led than for the books he has written.

In his early days he was known as ‘Captain Berserko,’ hanging out with such celebrity rebels as Peter Fonda and Jimmie Buffett, in addition to writers Richard Bratigan, Jim Harrison, Guy de la Valdene and artist Russell Chatham. His wives included the actress Elizabeth Ashley and Margo Kidder. Like Harrison, McGuane caroused on the margins of Hollywood, writing screenplays for Rancho Deluxe and The Missouri Breaks as well as the film adaptation of his picturesque, ‘faux crime novel’ Ninety-Two in the Shade.

I waded into Thomas McGuane mid-stream, in the 1990s when he published Nothing But Blue Skies and The Cadence of Grass. I’ve read all his fiction since — and enjoyed it immensely. I’m a great admirer of his non-fiction, collected in An Outside Chance (1981) and The Longest Silence (2000). Now approaching his 76th birthday, the Fly Fishing Hall of Fame inductee is one of the best fly angling writers on a crowed stream that includes many accomplished writers.

Over the past six months I ventured back to the beginning and read his debut novel The Sporting Club (1969) and the National Book Award finalist Ninety-Two in the Shade (1973). More recently I read his latest collection of short fiction Crow Fair, published by Knopf.

Comparing the earliest to the latest fiction, a reader can trace the arc of a writer who grew from a comic novelist of promise — eager to please, perhaps trying too hard for the laughs — to a mature writer of comedy, tinged with a patina of mundane tragedy, who examines the human condition with seemingly effortless ease and a graceful élan.

Like his longtime fishing buddy and fellow Michigander Jim Harrison, McGuane’s enduring subject is the precarious state of the contemporary male, a species forced to play bad hands in the card game of life, sometimes holding, occasionally folding, often bluffing, seldom winning. McGuane understands implicitly Henry David Thoreau’s notion of ’lives of quiet desperation.’

McGuane has ranched in Montana for many years and his stories are set in Big Sky Country and inhabited by Midwest Everymen caught up in, or entangled by, the pathetic rituals of everyday existence.

A couple of the 17 stories involve fishing — and infidelity. The prosaically titled An Old Man Who Liked to Fish tells of an elderly couple spending the day on the river. It turns out to be the last fishing opportunity for Edward, while Emily continues to massage the bitter suspicion that lingers from an affair committed by her husband years previously.

River Camp begins with the observation that a fishing trip on the Aleguketuk River is very much like heaven. But heaven soon descends into hell for longtime, uneasy brother-in-laws Tony and Jack when their strange guide Marvin ’Eldorado’ Hewlitt turns out to be someone different from what he appears.

A number of stories deal with ranching situations and circumstances. The protagonist in Motherlode earns a living by artificially inseminating cattle. In The Good Samaritan, Szabo operates a piece of land he insists is not a ranch, growing alfalfa for racehorse breeders.

Like Harrison, McGuane has remained on intimate terms with nature and he writes about wilderness as both external reality and inner reality with eloquence.

Love is in short supply in McGuane’s fiction, resembling a parched prairie drought. Romance customarily finds expression as lust and desire. Family relationships are fraught with unsuspecting dangers. Fidelity is made to be broken. Loneliness is the natural state of existence.

A number of redeeming qualities prevent readers from wanting to their slit their wrists reading McGuane.

He has grown into a master stylist. Reading him is a sensual pleasure. His insight into the human mind, heart and soul, especially as it pertains to boys becoming men and men reverting to boyhood, is piercingly perspicacious. And he is funny, not in a ha-ha, laugh-out-loud way, but in a way that peels back the protective veneer of human comedy, revealing heartache and sorrow.