There’s a small tattered black and white Kodak snapshot buried somewhere in an old photo album showing a smiling five-year old boy standing in front of the Christmas tree. He’s smiling because Santa brought him his first Detroit Red Wings jersey (red with its distinctive white winged-wheel), red pants with white stripe down the sides, gloves, shin pads and red socks with horizontal white stripes around the calves, along with a CCM hockey stick and pair of skates. (He didn’t get a jock until he started playing the game a couple of years later.)

The youngster is me and I’m happy because Santa knew my hero was Gordie Howe.

The athlete who became known as Mr Hockey was my first hero and the single reason I have loved hockey for all my remembered life, exceeding six decades. During the endless winters of childhood I lived for hockey.

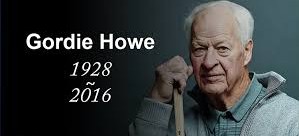

The hockey world, not to mention the world beyond, was saddened when it was announced that Howe had died June 10 at age 88. His long battle with health issues was well documented. His achievements on and off the ice were recorded in news reports around the world. Here are a few words expressing what Ol’ No 9 meant to me.

I remember Saturday nights when CBC carried Hockey Night in Canada, broadcasting only the second and third periods, with Foster Hewitt calling the game and Ward Cornell, from my hometown of London, Ontario, conducting between-period interviews. My bedtime was relaxed so I could watch the games, even if I was heavy eyed by game’s end. The contests I anticipated most were when the Red Wings played the Leafs at Maple Leaf Gardens.

Being a Red Wings fan led to my becoming a fan of the Tigers, Lions and Pistons. But the Wings were my rock and foundation. I remember all the greats from the mid-1950s onward: Sawchuck, Kelly, Ullman, Pronovost, Lindsay, Abel, Delvecchio, Crozier, Redman, Coffey, not to mention Yzerman, Fedorov, Larionov, Shanahan and Lidstrom, Datsyuk and Zetterberg. But Gordie stands alone and above, the first among the greats — one of the greatest ever to play Canada’s national game along with Lionel Conacher, Richard, Orr and Gretzky among a tight fist of others.

When I began playing in elementary school a pattern of insomnia set in that has tracked me throughout life. Sleep abandoned me when I retired to bed Friday nights in anticipation of early Saturday morning games. The hours I spent in classrooms in higher elementary grades dragged on interminably as I impatiently anticipated evening games under the magical lights of outdoor rinks.

I played elementary school squirt and peewee, after which I played minor and major bantam, minor and major midget and juvenile in the London Minor Hockey Association. Playing hockey on outdoor rinks was different from playing in arenas. You were victim to the elements. A heavy snowfall or freezing rain during a January thaw or in early March defined the game — fast and skilled or slow and sluggish. Persistent snow forced an unscheduled interruption in the game for a quick shovel. At game’s end the home team shovelled the ice before the predecessor of the Zamboni — a tank of water on small wheels with a horizontal pad that distributed water pulled by the arena attendant — provided a fresh layer of ice.

On my first Minor Hockey bantam team I was a year younger than my team mates. I had trouble skating because my skates were hand-me-downs from my dad with newspaper jammed in the toes. Sponsored by Redman Machine Shop, our team won the city championship. It would be the first and last time I played on a championship team. We received trophies and our team photo was published in the London Free Press — a thrill that lingered for years. I played intramural hockey during my four undergraduate years at Trent University. A pair of shoulder separations within six weeks in my last year ended my hockey career, such as it was. My dearest and most enduring friends from university, who I’ve known for close to half a century, were not guys with whom I studied but guys with whom I played hockey.

In my youth hockey was more than a sport. It was imprinted in the cold marrow of winter. Hockey warmed my imagination and comforted my dreams like a thick quilt on a long winter’s night. It was one of the things that brought my younger brother Steve, a Chicago Black Hawks fan, and me together. I collected hockey cards and other hockey paraphernalia bearing portraits of Original Six players, whether metal coins from bags of potato chips or plastic coins from boxes of instant pudding mix.

In West London we lived on a side street, which became a makeshift rink for games in which neighbourhood boys split up on opposing teams. Playing in the winter darkness after supper, under the illuminated spell of street lights was best, even if games were called when the tennis ball evaded recovery.

We had a backyard rink. I felt older than my years when, just before bedtime, my dad asked if I wanted to help him water the rink. It seemed colder than at any time during the day, but that was a small price to pay for being with my dad, a Toronto Maple Leafs fan who held the garden hose while smoke from his cigarette snaked skyward into the darkness of night. He would pass the hose to me and I tried my best to spread the water evenly from corner to corner to corner to corner.

Neighbourhood buddies, including my cousin Alan from across the street, came to play. We sometimes snatched a few minutes to play wearing galoshes when we didn’t have time to put on our skates, but my dad insisted we wear skates whenever possible.

Hockey builds character. I know this from experience. One season while in my teens I was cut from a team for the simple reason the coach didn’t like me. I wasn’t only disappointed; I was humiliated, mortified. In previous seasons I had been named team captain and co-captain and I knew I was more than good enough to make the team. I cried for hours behind the closed door of my bedroom when I got home. The following season I swallowed my embarrassment and rejoined the guys with whom I had always played. We lost in the city championship. I learned then, and have never forgotten, that life is not always just.

I thought I had put hockey behind me until my second son, Robertson, was born. Unlike his older brother Dylan, Robin loved hockey from infancy. He watched games with me before getting the irrepressible urge to get on the floor and play an improvised game with plastic ministicks and a rolled up pair of socks. Like his grandfather, he became a Leafs fan while his grandmother remained a steadfast Wings fan like his father.

In Robin’s first year of house league hockey he made the permanent switch from forward to goalie after scoring his one and only goal on ice. He played between the posts until his teen years. He won a couple of league championships and a regional championship. He also was the only goalie on a team that lost every game that season. Did I mention that hockey builds character?

Robin is high-functioning autistic. He was speech delayed as a child and he had difficulty expressing himself, especially his emotions and feelings. Hockey has provided Robin and me with the vocabulary through which we express our love for one another. Since he was seven we have attended hockey games together, watching the London Knights play arch rivals Rangers at the Aud, and Storm at the Sleeman Centre, among other rivals in other arenas. My family attended Junior B London Nationals’ games at The Gardens before the team advanced to Junior A as the Knights, later to play at the John Labatt Centre and Budweiser Gardens in downtown London.

Robin and I have gone to the Air Canada Centre to see the Leafs and this past winter I took him to the Joe Louis Arena to watch the Leafs and Red Wings. I wanted him to see the Joe before the end. One of the heartaching highlights of my childhood was watching the Red Wings lose to the Black Hawks on a Sunday afternoon at the Olympia.

Hockey has played an important role in my life and I owe it to Gordie Howe, Mr Hockey, my first and most enduring hero. History confirms I chose wisely. His life is a model of how legends are made.

Goodbye and God speed, Gordie — and thank you.

Canadian Hockey Literature

Hockey fans with a literary bent, or literary readers with a hockey bent, can find much to enjoy in Canadian literature. My pair of all-time favourites is David Adams Richards’ charming memoir Hockey Dreams: Memories of a Man Who Couldn’t Play and Paul Quarrington’s comic novel King Leary (he also wrote Original Six), followed closely my Steven Galloway’s magical Finnie Walsh, Richard Wright’s The Age of Longing and Roch Carrier’s Our Life with The Rocket. Of course Carrier wrote the classic children’s book The Hockey Sweater).

There’s also Bill Gaston’s The Good Body and Roy MacGregor’s The Last Season. MacGregor is the author of the Screech Owl children’s mystery series as well as The Home Team: Fathers, Sons & Hockey, The Seven A.M. Practice, Road Games: A Year in the Life of the NHL, Home Game: Hockey and Life in Canada, co-authored with Ken Dryden.

I highly recommend all of these titles. For those who want to learn about Canada’s national sport in literature check out Jason Blake’s Canadian Hockey Literature (University of Toronto Press). The best biography on Howe is Roy MacSkimming’s unauthorized Gordie: A Hockey Legend. Brian McFarlane’s Original Six instalment The Red Wings provides a snapshot of Howe’s Red Wings’ years.

Although I seldom read as a kid, Scott Young’s Scrubs on Skates, Boy on Defense and Boy at the Leafs Camp were books I treasured. I gave Robin this trio of young adult classics as Christmas presents one a year.