One of the deepest pleasures afforded readers of fiction is discovering a writer through synchronicity, as if you were destined to find a specific writer in the dense wilderness of literature. It’s a gift bestowed on readers by inquisitive literary gods.

This happened to me most recently with a couple of writers born and raised in Appalachia, where they continue to live and write — David Joy and Ron Rash. It so happens they are close friends who share a love of fly fishing on pristine mountain streams in pursuit of ferociously beautiful native (wild as opposed to hatchery) brook trout or ‘specks.’

While visiting my partner Lois’ sister in North Carolina, we visited a used bookstore in Asheville, home of Thomas Wolfe. I wanted to pick up a bag of books by North Carolinian writers, two of which — One Foot in Eden and Saints at the River — were written by Rash. I knew nothing of the author at the time and the two novels, his debut and sophomore as it turns out, sat untouched in my study for a year.

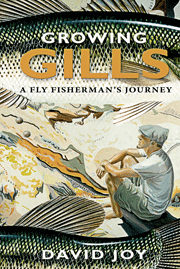

My path of literary discovery took a fortuitous detour when I read a book review of a young North Carolinian writer with whom I was unfamiliar. Not only was the review of Where All Light Tends to Go bursting at the seams with praise (well deserving as I subsequently learned), it mentioned that Joy’s first book was a memoir about fly fishing. I immediately acquired Growing Gills: A Fly Fisherman’s Journey. It was both incandescent and revelatory. I was so impressed with this extraordinary account of fly fishing I added his debut novel to my bucket list of must-reads.

While reading Growing Gills I learned Rash was one of Joy’s dearest fishing companions. In his memoir Joy expresses great admiration and respect for Rash, the man and the writer. This is what Joy says: An author and friend of mine, Ron Rash, had been asking me to take him fishing for years. I knew his love for Appalachia, fly fishing and native trout from reading his words. His descriptions are alive, so I never doubted that he had been there and that he shared my passion. . . . Through time, our friendship had grown past a master-apprentice relationship in a creative writing classroom and blossomed into a mutual respect for wild places.

Growing Gills led me to the fierce wonders of Where All Light Tends to Go, whose terrible beauty is heartbreaking and breathtaking. With his debut novel, Joy has joined the company of such American rural gothic-noir masters as Tom Franklin, Daniel Woodrell, the late William Gay and, yes, Rash.

After reading Where All Light Tends to Go I hungrily consumed One Foot in Eden and Saints at the River. I was so impressed I acquired Rash’s bestselling novel Serena, latest novel Above the Waterfall and volume of selected short stories Something Rich and Strange. After devouring Above the Waterfall in 24 hours, I dug into Serena, which has been adapted into a feature film. I can’t wait to begin his selected stories. Rash is also a poet, so I’m eagerly anticipating Poems: New and Selected, which is being released next spring.

Now, what is it about Joy and Rash I enjoy so intensely? Like Thomas Hardy and William Faulkner, they share a concentrated attachment to place, which is embodied and enacted in their writing. Place is as much character as setting. Place not only frames the story but is painted into the picture. Place is a component of both form and content.

This should not be misconstrued as, or confused with, regional writing. Local colour is woven into the textured fabric of personality — bred in the bone, as it were. Temperament and behaviour are intimately and inextricably bound up with geography and history, culture and myth. Land embodies and reflects psychological and emotional realities. Landscape is both mindscape and soulscape.

Place is synonymous with home and family and the passing down of traditions and beliefs through generations reaching back into the distant past. The lives of individuals, their very destinies, are defined and determined by place. Fate and landscape are twins joined at the hip of a sympathetic imagination. By penetrating the heart of a specific place, Joy and Rash divine universal and timeless truths.

Joy and Rash are as true to Appalachia as Alice Munro is to southwestern Ontario or as David Adams Richards is to the Miramichi in New Brunswick. They most closely resemble Richards, a literary soulmate and fellow fly angler, in terms of a driving moral imperative which is Dostoyevskian in thrust.

I now want to turn to the aesthetic splendours of Growing Gills. The title is apt because it describes exactly how Joy relates to, and identifies with, fishing generally and to fly fishing specifically. It is neither sport or recreation, pastime or avocation. Rather it is an experience the English poet John Keats identifies as negative capability, meaning the creative ability ‘of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’

This is how Joy introduces the matter: I know that most families have stories of fishing trips, but with mine it’s a little different. These aren’t tales told and born anew each time everyone’s back together. These aren’t stories marking the one or two outings when a father took a son fishing. These stories are our lives, the cornerstone of our existence, the reason that we continue to wake up and give the world another go. The tales are points along our linear journey through this world and the only thing to assure us that we ever lived. In the quilt work of our lives these are the patches stitched together by our breathing, the only thing that holds it all together. Fishing is not a hobby, it is who we are.

This not overheated hyperbole or lyrical exaggeration. Read Growing Gills and discover for yourself. As I was reading and rereading passages that touched the very essence of fish, fishing and fly fishing, I was reminded of a term first developed by Sigmund Freud — ‘polymorphous perversity’ — but without its conventional sexual associations.

After catching his first wild speck, Joy recalls: Since that first native trout, I’ve spent thousands of hours on the water in search of this fish. . . The fish that were once mythical have become so real that I can smell their sweet, earthy aroma emanating from my hands, even on those days that I’ve not touched water. I am haunted by their existence and by knowing they are holding steady in the current just out of sight. . . When I am left to my thoughts nothing else swims through my mind but trout and ways to catch them. I daydream of drag-free drifts over rising trout and of watching the slow methodical ascent of feeding fish.

I haven’t found any other fish comparable to trout: brown trout with pitch black spots covering the colours blending down their bodies from raw umber to buttery yellow like the top of a perfectly baked biscuit; rainbows with rosy cheeks, moss green backs, cherry red lateral lines, and black specks sprinkled like pepper; and brook trout resembling marble slabs delicately brushed and speckled with brilliant yellows, oranges and reds. These fish are masterpieces of the natural world, paintings that do not need another stroke. Every encounter is an art show; the stream is my Louvre.

Footnote: Since posting this blog I have read Rash’s Poems, which is exceptional. My only complaint is that the collection isn’t longer. I eagerly anticipate the day a complete poems is published. As well I have read four other North Carolinian writers I greatly admired — Wiley Cash, Howard Owen Lee Smith and Fred Chappell. I was completed won over by Chappell’s quartet of semi-autobiographical fiction encompassing I Am One of You Forever, Brighten the Corner Where You Are, Farewell I’m Bound to Leave You and Look Back All the Green Valley. His collection of new and selected stories, Ancestors and Others, is also a rich treat. I picked up a couple of his poetry collections — Midquest and Spring Garden — which I have yet to read. I cannot recommend Shappell enough. He is one of the great contemporary Southern writers.

(Featured image of David Joy)