It’s just a way to while away the time until you die.

— Guy Clark on songwriting

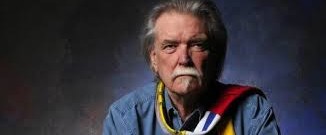

I was deeply saddened when I heard from a friend that Guy Clark died three days ago on May 17 at his home in Nashville after a long illness. He was 74. The Grammy winner was one of the most respected singer/songwriters of his generation. Born and raised in Texas, he was as much a poet as a country musician, a natural storyteller who was a modern troubadour — a bard and a raconteur with a whiskey in one hand and a guitar in the other.

Clark never found widespread fame despite his mastery of song that endeared him to songwriters and performers of varied genres and styles. Like melodic dreams on the wings of prayer, his narrative songs transcended time and place, giving eloquent expression to eternal truths. Clark died a few weeks after the great country artist Merle Haggard, another master of songcraft.

I’ll never forget the first time I talked to Clark. I had wanted to interview the celebrated artist for some time. He had been a fave since my boisterous days at Peterborough’s Trent University in the 1970s, when Clark was part of the Texas posse riding shotgun for Jerry Jeff Walker, a hard-partying alt-country pioneer who penned such classics as Mr. Bojangles and Railroad Lady (the latter co-written with Jimmy Margaritaville Buffett).

But the phone call I made to Clark is forever burned into my consciousness for another, more devastating, reason. It occurred in the morning of Sept. 11, 2001 — the day of infamy abbreviated as 9/11.

I was shaking at 11 am. when I called Clark at his Nashville home because the newsroom of the Waterloo Region Record — no different from newsrooms across North American and abroad — was in a state of collective shock, as reporters, photographers and editors remained glued to televised news coverage of the horror of the Twin Towers in New York City.

I asked Clark — who I was interviewing in advance of his appearance at the second annual Canadian Songwriters’ Festival at Guelph’s River Run Centre — if he wanted to reschedule the interview. He answered with a quiet insistent ‘no,’ adding, ‘it’s what we do. It’s what we need to keep on doing.’ I took a deep breath, collected my composure and did what I did — ask questions. He answered simply and directly in a drawl he had not lost after honing his craft as one of America’s great songwriters in the Lone Star State.

Clark talked as he walked when I subsequently saw him on stage — with a quiet dignity that you find in certain hard-working, blue-collar stiffs who are proud but neither boastful nor loud. If you are searching for one word to describe him, look no further than integrity. It seeped out of his pores.

We started by discussing his most recent album at the time Cold Dog Soup. The title track references one of my favourite poets, only in unfamiliar duds: ‘William Butler Yeats in jeans.’ He denied the line was self-referential. ‘I would’t presume to compare myself to William Butler Yeats,’ he asserted. ‘It’s meant to represent all singer/songwriters.’ Still, there are many — including his longtime friend and occasional writing partner Emmylou Harris who calls him Nashville’s Poet Laureate — who would agree the description fits Clark like a pair of weathered Levis.

While reluctant to make large claims for himself, Clark conceded he views songwriting as a form of poetry. ‘The thing about lyrics is that they have to work on paper separate from the music.’ Similarly, when asked about advice he would give aspiring songwriters, he stressed the importance of words. ‘You have to pay attention to the English language,’ he said, sounding like a high school English teacher. Artistic references are sprinkled throughout his oeuvre including songs with such titles as Hemingway’s Whiskey, Picasso’s Mandolin, Maybe I Can Paint Over That and High Price of Inspiration.

Although he had no major hits over a career exceeding half a century and enjoyed neither the fame nor the fortune his talent so richly deserves, Clark’s stature as a master songwriter remains unequivocal. Celebrated as a songwriter’s songwriter, his best work slides through the door of music and enters the living room of poetry.

Desperados Waiting for a Train, Texas 1947, The Randall Knife, The Last Gunfighter Ballad, That Old Time Feeling, The Houston Kid, A Nickel for the Fiddler and Like a Coat from the Cold, to name a few examples, are revered as much for their literary value as for their catchy melodies that whisper in the ears of attentive listeners.

Clark recorded around 20 albums since 1975, but paid the bills largely through royalties. A partial list of artists who have covered his songs includes Walker and Harris, in addition to Mary Chapin Carpenter, Rita Coolidge, Rodney Crowell, Nanci Griffith, Kathy Mattea, Vince Gill, Lyle Lovett, Tom Rush, Earl Scruggs, Marty Stuart, Ricky Skaggs, Alan Jackson, Brad Paisley, Kenny Chesney, George Strait and Buffett, in addition to the late quartet of Townes Van Zandt, Waylon Jennings, John Denver, Johnny Cash. Similarly, the list of songwriters he has influenced — including Steve Earle (who played bass in Clark’s first band), Lucinda Williams and Robert Earl Keen — is equally long and impressive.

Clark emerged in the early 1970s as one of the young song-slingers drawn to the musical renegade Walker, along with the likes of Gary P. Nunn and Ray Wylie Hubbard. The only time he got a tad testy in the interview was when I asked him directly about Walker. ‘I got over Jerry Jeff a long time ago,’ he snapped.

Indeed, Clark never was a sheepish acolyte. He was one of a gifted generation of artists who defined the phrase ‘Texas poetic songwriting tradition’ encompassing Van Zandt, Jimmy Dale Gilmore, Joe Ely, Butch Hancock and Billy Joe Shaver, not to mention elder music cowpokes Willie Nelson and Jennings who gave the royal finger to Nashville to embrace the thriving music scene of their home state centred in Austin.

When asked what produced such a talented generation of songwriters Clark didn’t miss a beat in attributing it to an outlaw attitude. ‘Maybe it has something to do with the knowledge that you could do anything you wanted to do. There weren’t any rules —and this applied to more than songwriting.’

Clark moved to Nashville with his late wife Susanna in 1971 after living in Los Angeles for a time, documented in his early ditty L.A. Freeway. Although the songwriter left Texas, Texas never left the songwriter. ‘I live in Nashville, where the business is, but Texas is home,’ he acknowledged.

A longtime maker of custom guitars, Clark applied that same meticulous craftsmanship to songwriting. In fact, a compilation of three early albums is simply called Craftsman. He also wrote songs (The Carpenter and Jack of All Trades) and released albums that reference craftsmanship including Workbench Songs and Boats to Build. Nonetheless, he didn’t advance any theories about the craft of songwriting, other than to observe that a song has to embody a particular kind of truth in order to be authentic. ‘Truth is always stranger than fiction. I couldn’t make up some of the things I’ve put in songs.’

On the cusp of 60 at the time I first talked to him, Clark confirmed he approached songwriting differently from when he was younger. ‘I was never interested in becoming a star. I was always interested in the quality of the work. All I ever wanted was to write songs that I’d always want to sing. That’s all I’ve ever tried to do.’ There’s no need of qualification here. It’s what Clark always did. The proof remains in songs that will endure as long people cherish the Great American Songbook.

When the plug was pulled on the Canadian Songwriters’ Festival after five years of inexplicable disappointment, the River Run Centre insisted it would continue presenting premium live music. As proof of its commitment, it invited Clark back in 2005 with longtime musical compadre Verlon Thompson.

As he did four years earlier, Clark served up the kind of wry, understated and self-deprecating performance that fits his songs like a pair of stonewashed jeans. ‘We’re going to do some songs we likely know, ” he deadpanned.

Repeating a familiar pattern, he leisurely fingerpicked his way through a poetic songbook spanning four decades. He didn’t mail in a greatest hits package. Instead, he hand-delivered a rarer and more precious parcel of masterful songs including Desperadoes Waiting for a Train, L.A. Freeway, Black Diamond Strings, Homegrown Tomatoes and Soldier’s Joy 1864.

Clark continued to attract a rich bouquet of superlatives until the end, but the truest description is that of storyteller. He didn’t so much sing as ramble his way through narratives set to music in the time-honoured tradition of itinerant troubadours and, even before them, oral storytellers or bards who sat around fires and cast spells of enchantment that revealed to listeners their innermost being.

His best songs have always been simple stories, told in a deceptively simple manner and set to simple melodies. But don’t be fooled by the word ‘simple.’ His songs are oral literature, worthy of being passed down through generations. Try removing a word or two and the lyric collapses like match sticks in a windstorm. For that matter, try another melody and the tune slips away like dust that hasn’t tasted rain for a month.

Clark always spoke from the heart to the heart of matters of the heart. Sounds easy. But, again, don’t be fooled. It’s treacherous business that exacts a high price because it unmasks pretenders, frauds, cheaters and wannabes. Only honesty and truth make the cut — like a pair of old blue jeans. Take that, Mr. Yeats.

Here’s footage of a younger Guy Clark singing one of his masterworks, bridging the sometimes vast distance that divides the young from the old through deep affection that men are reluctant to acknowledge as love.

Here’s concert footage of the old song-slinger as he was a couple years ago, with longtime music sidekick Verlon Thompson on guitar and harmony vocals. Clark’s voice always reminded me of a parched Texas crossroads at the height of summer — where mortality and art intersect. Lovely.

Happy Trails, Guy.