I joined KW Flyfishers in 2008, a year after I picked up a fly rod for the first time. Like the great Groucho Marx who famously mused, ‘I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member,’ I’m not by nature or temperament a joiner of clubs. Nonetheless, I take deep delight in this particular organization, having served as a director, vice-president and secretary.

I highly recommend all beginners seek out such clubs as an integral part of their fly fishing apprenticeship. Not only have I learned a great deal, I have made some lasting angling friendships. One of the most charming members I met early on was Joan Kirkham, an avid fly angler and master fly tyer.

Although there have been some notable female anglers throughout the long history of fly fishing, from Dame Juliana Berners to Joan Wulff, fly fishing remains a predominantly male activity. Consequently, fly fishing clubs tend to be men-only bastions. All of which makes Kirkham — a founder and honorary lifetime member of KW Flyfishers — an exception to the rule.

I talked to Kirkham in June, 2008 for a feature for the Waterloo Region Record, where I worked as an arts reporter with a newly found passion for fly fishing. (I must say that in 40 years of newspaper journalism I interviewed few subjects more charmingly reluctant than Kirkham. She avoids attention as if it were a cloud of black flies on a trout stream.)

Kirkham started fly fishing after she immigrated to Canada from England in 1953. Her husband, Dave, was an enthusiastic golfer who had little time for fishing because of business responsibilities. So when their 11-year-old son, Steven, wanted to buy a fly rod, mom answered the call. ‘I had no idea about fly fishing,’ Kirkham said at the time from her Cambridge home, within easy walking distance of the Grand River. ‘My idea of a fly was something you hit with a fly swatter.’

Nonetheless, she bought her son ‘a rinky dinky fly rod’ and started taking him fishing. Determined not to ‘miss out on the fun,’ she began fishing with a spinning outfit.

Mom and son were fishing one day when they saw a fly fisherman catch a fish. ‘I decided to try a couple of casts with Steven’s rod.’ After ‘lashing the water into a foam and catching every leaf and twig in sight,’ Kirkham eventually became adept at casting.

It wasn’t long before Steven told his mom he needed his own flies. Again, she answered the call by buying a beginner’s fly-tying set at a department store. ’It was a load of rubbish,’ she snaps. Steven grew frustrated with the shoddy material, so mom tried her hand at the delicate art of imitating insects with feather and fur.

Initially, she had no more success than her son, but patience and persistence paid off, and she was soon tying flies. A few months later, Kirkham was in a tackle shop when she overheard an angler complain about being unable to get his hands on good flies. ‘I brazenly said I was a fly tyer,’ she confesses with a modest chuckle. Within three months, she ‘couldn’t keep up with the demand.’

This seems the appropriate place to digress and point to a few women who have gained distinction in the fly angling fraternity by tying flies that transcend craft and become art.

Among them is legendary English-born fly tyer Megan Boyd who made flies for royalty from the seclusion of her tiny cottage in Kintradwell, near Brora, Scotland. Best known for her Atlantic salmon patterns, she was awarded the British Empire Medal in 1971. Filmmaker Eric Steel produced and directed a magical animated documentary on Boyd titled Kiss the Water. In the 2014 film, Country Life fishing editor David Profumo, who apprenticed with Boyd for a summer during his youth, describes her as follows: ‘She had the most delicate feminine hands; her creations were the Fabergés of the fishing world. You could say she wove a certain kind of magic.’

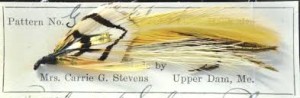

Then there’s Maine’s Carrie Stevens whose designs include the famous Grey Ghost among others. There’s also the legendary Catskill husband-and-wife couples of Elsie and Harry Darbee (whom legendary angling writer Sparse Grey Hackle called ‘the world’s best fly tiers’) and Winnie and Walt Dette and their daughter Mary.

Following in the tradition of Boyd and Stevens and the Catskill fly tying matriarchs, Kirkham proved highly accomplished at tying flies. And her skills were not lost on the fly fishing fraternity. The late Ian Colin James, one of Canada’s most prominent professional instructors, tyers and guides, acknowledges Kirkham in his entertaining memoir Fumbling with a Flyrod as ‘one of Canada’s best tiers and an inspiration to all who own a vise.’ James once told me that meeting Kirkham ‘was like meeting Wayne Gretzky.’

Kirkham’s goal in tying flies is elegant in its simplicity. ‘I want a fly that looks good to my eye and that looks good to a fish’s eye.’ When asked about the pleasure she gets from tying, she draws a domestic comparison. ‘It’s the satisfaction that comes with doing something as well as you can, like baking a terrific pie or cake.’

In the 1970s, Kirkham got together with a half dozen fellow fly anglers. When the group dispersed, Kirkham and her friend, Ruth Zinck, were determined to continue meeting. They rented a room at the Breithaupt Centre and soon word spread about a newly formed fly fishing club, which became KW Flyfishers.

Ironically, a club owing so much to two women was soon dominated by men. Over the years, no more than a half dozen women have joined. Notwithstanding the disproportionate numbers, the club’s male members — she refers to them as ‘gentlemen’ — have always treated Kirkham with collegial respect.

She received a warm and enthusiastic ovation in 2008 when she joined the ranks of ‘a very select group’ and was inducted as a lifetime member.

Kirkham concedes being a woman in a man’s sport has been challenging. ‘At first fly fishermen would look at you slightly askance,’ she recalls, adding that she has always felt women ‘had to be a little bit better than average to be accepted.’ She need not have worried; she passed with flying fur & feather.

Nonetheless, Kirkham believes strongly that fly fishing has much to offer women, who (she contends) are temperamentally predisposed to doing it well. ‘Fly fishing requires patience and women are patient. They don’t need the immediate gratification men do.’ Amend to that.

Fast Forward to 2016: I telephoned Joan and explained that I had updated my original feature for my blog, which I began as a retirement project. I told her, with some considerable trepidation, that I wanted to take a couple of photos of flies to accompany the posting. She declined with apologies, explaining that the month in which I called was booked solid. In fairness, her husband David was not feeling well. Nonetheless, I experienced déjà vu because I recalled how difficult it was to arrange a sitting with a Record photographer when I wrote the newspaper feature. Joan hates a fuss, especially when she is the topic of interest. The dark cloud under which I was casting had a silver lining, however. She confirmed that she was still tying flies. I was overjoyed.

Below is the recipe for tying one of Kirkham’s original fly patterns, KIRKHAM’S CRAY.

The article (which I have edited) was published in May 2002 on the International Federation of Fly Fishes website.

By Ruth J. Zinck and Bob Bates

The Kirkham’s Cray by Ruth Zinck caught my eye as I flipped through the 1990 Patterns of the Masters. I asked Ruth if I could use the information for a Fly of the Month. She said yes and sent me a fly to photograph. Most of the information given below was copied from Patterns of the Masters. A few of my comments have been added.

‘Joan Kirkham lives in Cambridge, Ontario and is one of the best and most creative tiers I know. She is also a dear friend and when I get east, spending hours talking tying with her is always a highlight of the trip. She showed me her crayfish pattern in June, 1989 and gave me permission to tell the world at Conclave.

Fishing Suggestions:

We know that bass like to eat crayfish. Kirkham’s Cray should be crawled over the rocky bottom of a lake or river and occasionally retrieved in short spurts. Depending on water depth, use a sink tip, full-sink line or weighted leader. However, I once got a good strike on the fly just as it hit the water.

One crayfish angler in Washington State fishes rocky shorelines and catches trout. He says: cast toward shore from your boat or float tube, and let the fly bounce down the rocks. Use a slow hand twist retrieve to imitate a crayfish’s walking movements, and a two- to three- inch strip retrieve with a pause to simulate their quick movements.

Large trout also savour a dinner of crayfish.

Materials:

Hook: Mustad 79580 or 9672, Daiichi 2220 or 1720, Dai-Riki 700 or 710 or similar hooks, size 10

Thread: Black or brown Monocord

Back: Red fox squirrel (use long hair from middle area on top side of tail)

Head and Body: Medium size, brown/black, variegated chenille Rib: 6-lb test clear monofilament

Claws: Red fox squirrel (as above)

Tying Steps:

1. Wrap thread to bend. Cut a bunch of squirrel hair slightly larger than a household match. Hold near tips and comb out short hair. Tie in remainder by butts on top of hook with most of hair extending beyond bend of hook. Trim butts at an angle, and wrap over cut ends. Return thread to bend.

2. Head: Tie in chenille, and wrap to 1/4 shank length from bend. Secure, half hitch and then move chenille to a material holder to clear work area. (Expose thread core by stripping off fuzzy chenille to make tie in easier.)

3. Burn one end of an 8″ piece of monofilament to make a small blob. Tie the blob end in on top of the hook at the half hitch. The blob will prevent the mono from pulling out. The rest of the mono should be moved to the material holder.

4. Right claw: Cut a bunch of squirrel hair slightly smaller than a household match. Comb out short hair, and use a hair stacker to even the tips. With tips of hair toward bend, wrap one circle of tying thread around the bunch and then place it on the far side of the hook. Tips should protrude about 1 inch to left of thread. Tie down firmly.

5. Tie down butt ends of claw along top left side of hook to 1/8″ from eye. Trim butts at an angle.

6. Left claw: Return thread to right claw tie-in point. Repeat steps 4 and 5 on near side of hook.

7. Wrap both sets of trimmed butts.

8. Wrap monofilament clockwise around base of right claw 2 to 3 times. Bring monofilament under hook and wrap left claw counter-clockwise finishing across top of hook on eye side of claws. Make one turn around hook. Keep tension on mono.

9. Wrap thread to monofilament and tie down. DO NOT CUT. Mono should extend beyond far side of hook. Return thread to eye.

10. Cover wrapped squirrel body and base of claws with head cement. 11. Wind chenille to within 1/8″ from eye and tie off. Trim.

12. Bring squirrel hair over chenille and, pulling it TIGHT, tie down at eye. DO NOT TRIM.

13. Wrap monofilament around body in wide spirals toward eye. First wrap should be close to base of claws. Tie down well. Trim.

14. Whip finish under tail at eye. Use head cement on tail wraps and whip finish. Cut tail 1/4″ beyond eye.

The last step in any fly tying project is to take your gems out to your favorite body of water. Apply your knowledge as to where bass might be hanging out around rocky areas with crayfish. Carefully creep your fly along the bottom, and be ready for a fight with a lunker.

(Featured image of A Graceful Rise, a salmon fly pattern created by Megan Boyd)