My fly angling buddy Dan Kennaley has a fishing dog. His nine-year-old golden retriever Maggie spends hours trying to catch minnows in the shallow waters in front of the cottage Dan shares with his family on a postcard lake in Muskoka.

Exercising the Two Ps of Fly Fishing Maggie’s methodology is a model of patience and persistence. With the exception of her wagging tail, she stands perfectly still for as long as it takes to spot a trespassing minnow before lunging at it. Her powers of concentration are a wonder to behold. She never concedes to disappointment when she comes up empty. Hope and optimism are her mantra. Like any sympathetic dog owner, Dan spoke for Maggie when he told my partner Lois that, ‘After all, it’s called fishing, not catching,’

Fly anglers can learn a lot from Maggie, as Dan and I did during an evening of fishing on a nearby private lake. The lake — which will remain unidentified — is small and isolated, although located close to a highway. At present there are no cottages populating its shore. On this particular evening we shared its tranquility with a solitary resident loon and a hawk that watched from on high in an adjacent white pine.

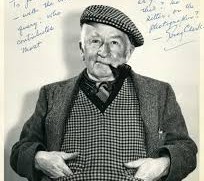

It was about six o’clock when Dan and I got his trusty aluminum canoe on the water, which was flat and still. Dan has had the canoe — named Greg Clark after the legendary Canadian newspaper journalist and outdoor writer — since his university days more than 30 years ago. Its bright hand-painted red exterior has faded with time including annual fishing trips to Algonquin Park after the ice goes out and before the dreaded black fly invasion.

It was hot and humid on the summit of summer as we paddled to the far shore. We began casting streamers. Dan elected a Mickey Finn, a classic yellow and red bucktail his hero Clark had a hand in naming.

I must digress to trace the story of the Mickey Finn. You don’t have to be an angler to recognize that the original Mickey Finn is not a fly pattern, but a drink ‘spiced up’ with a drug. Reputed to have been named after a bartender in Chicago, the rumour persists that the drink caused the death of movie star Rudolph Valentino. Clark, who initially wrote about the fly in 1937, reasoned it was as deadly as the drink.

The fly pattern’s history predates Clark’s involvement. It was originally designed by Quebec fly tier Charles Langevin in the 19th century. Known initially as The Langevin, it was later renamed The Assassin because of its brook trout killing power. This incarnation of the fly was popularized by American outdoor writer John Alden Knight. The story goes that Knight and Clark went fishing on Ontario’s Mad River in 1936 when Clark observed that the fly was as deadly as the notorious drink. The name stuck and the fly has been known as the Mickey Finn ever since. There are numerous recipes for the fly, some incorporating tinsel, Krystal flash and jungle cock eyes.

For my part on the evening in question, I relied on a black bead-headed woolly bugger I purchased at a fly shop the previous winter in Victoria, B.C. (Dan ties a black woolly bugger with a red marabou tail which is a killer on the lake.)

Save for a couple of strikes that failed to translate into landed large or smallmouth bass, we were both skunked. In contrast to Maggie’s worthy example of hope and optimism, we were frustrated after a couple of futile hours, if not downright disappointed. After all, who could be disappointed fishing on such an evening, on such a lake? Nonetheless we took our cue from Maggie with respect to the Two Ps.

Just as the sun was slipping effortlessly behind the conifers and hardwoods on the western shore Dan suggested we paddle across the lake to the near side, where we put in the canoe, and try some poppers.

Dan fishes the lake regularly and often fishes both sides, near and far. But I get the opportunity only once a year when Dan and his wife Jan invite Lois and me for a couple of days of Muskoka cottage life. I had never fished the near shore before, for the very good reason that we had always caught sufficient bass on the far side to satisfy self-imposed catch-and-release limits.

We started casting poppers. Dan and I both chose green frog patterns with yellow and black bulls-eye spots. Mine was store-bought but Dan had made his own from rubber flip-flops — ugly as hell (sorry Dan) but effective. Both sprouted long thin rubbery legs.

I had two strikes on the first two casts. Yippee.

Our luck had changed, whether it was the result of the time — known as the witching hour by some fishermen or as the gloaming by my Celtic ancestors — changing locations or changing fly patterns. Or perhaps all three factors — or any combination of the above.

Fishermen who use bait-casting, spinning or spin-casting reels will be familiar with the allure of hard, top-water lures, whether Hula Poppers, Jitterbugs or Crazy Crawlers to name three of the most popular brand-name styles. There’s something irrepressibly attractive and delightfully addictive about watching voracious bass leap out of the water to smash or pound top-water lures. There’s nothing like it in freshwater fishing with the possible exception of casting surface lures in shallow water at Northern Pike.

The secret to poppers is applying Maggie’s Two Ps — patience and persistence. Cast to all the likely places. Think like a bass. Look for structure: pockets among beds of lily pads, edges of fall-offs and weed beds, half-submerged trees, dark holes under overhanging bushes and shadows around rocks and boulders — docks if there are any, but I prefer undeveloped lakes and rivers.

On your initial cast let the popper sit until all the outwardly expanding rings vanish. Take your time; this is part of the Zen of fishing.

When the concentric ripples have disappeared, give your rod a short, sharp flick. This is rapid wrist action, causing the tip of your rod to move suddenly and with authority. This action causes the burble that drive bass to distraction.

The late William Tapply, the fine mystery novelist and outdoor writer (Opening Day & Other Neuroses, Home Water Near & Far, A Fishing Life, Bass Bug Fishing, Pocket Water, Trout Eyes, Gone Fishin’), claims it’s the sound of prey moving on the water’s surface, not its profile or colour, that triggers bass to strike. He asserts that you should impart various lifelike noises to a bug popper. Give it a sharp tug to make it go ‘ploop’; a twitch to make it ‘burble’; an erratic jerky retrieve to make it ‘chug, glug and gurgle.’

Let it rest after each rod twitch. Wait until the expanding rings dissipate. Slowly count to 20, if you lack patience. Like all accomplished anglers, Tapply veers from the acquired wisdom advocating definite rest stops by recommending that you create a little flutter, like a heartbeat in the breast of a sleeping dog. Effective bass poppers are never entirely motionless, he contends in Bass Bug Fishing. Even at rest they should ‘shiver, shudder, quiver and flutter.’ Sounds tantalizingly sexual, doesn’t it?

Remember, your popper should fall upon the water with a muffled splat or plop. If it lands soundlessly, nearby bass won’t hear it; if it crashes on the surface like a tossed rock, they’ll hit the road, Jack.

Dan and I both caught five bass on that lovely evening. We also had plenty of hits we failed to set, which is par for the course for anglers of all dispositions and inclinations. I failed to land a respectable bass that was spooked as soon as it spotted the canoe.

All of my landed bass were largemouth, spanning from nine to 15 inches. The 13-incher (measured) was exciting; the 15-incher (measured) was thrilling. The latter caused my Montana-made Scott seven-weight rod to arc nicely. It actually pulled the canoe around as I tucked the rod’s butt into my belly for leverage. On two occasions Dan and I had doubleheaders — a sports term that denotes two anglers catching fish at the same time. TV angling companions routinely crow collegiately whenever they land a pair of fish simultaneously. Talk about fun.