Robertson Davies was a cunning literary prestidigitator whose legerdemain spanned the breadth of his writing. After all, he disguised Fifth Business, his masterwork, as an epistolary novel rather than acknowledge that it is a postmodern fusion of spiritual autobiography and romance quest in the shape of C.G. Jung’s myth of individuation. Similarly, while written as a letter to his headmaster, the novel is actually a death-bed confession seeking redemption from no less a figure than God.

Davies was both an obsessive and a compulsive diarist. As such he earned the distinction of being the greatest diarist in the history of Canadian arts and letters. Initially we had his fictional ‘diaries.’ Now we have the publication of his personal diaries gleaned from numerous journals Davies dutifully and judiciously kept throughout his storied life.

The writings attributed to Samuel Marchbanks aren’t actually diaries, but a series of acerbic reflections on life, manners and literature initially published in the Peterborough Examiner when Davies was editor and publisher. The weekly newspaper column, upon which much of his early reputation rests, was later collected in three volumes — The Diary of Samuel Marchbanks, The Table Talk of Samuel Marchbanks and Marchbank’s Garland — before being edited by the author and published in 1985 in a compendium volume as The Papers of Samuel Marchbanks.

The sleight-of-hand arises from the fact that while diaries are personal and private, the commentaries penned by Davies’ satirical doppelgänger are intended for mass consumption and public entertainment. Davies once confided that his curmudgeonly alter ego reflected the ‘clownish, anarchic, Rabelaisian side of (his) nature.’

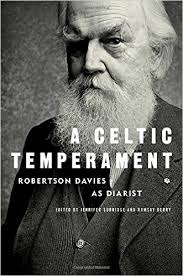

Subtitled Robertson Davies as Diarist, A Celtic Temperament is most assuredly the first published instalment in a projected series. It’s not only monumental, but the most extensive and comprehensive literary diary ever published in Canada. The volume arrives twenty years after Davies’ death, in accordance with his wishes to protect the innocent and guilty alike. It spans five years between 1959, when Davies turns 46, and 1963.

Davies undoubtedly wrote his diaries with an eye on future publication. ‘Would my diaries, edited, eventually make an autobiography,’ he wonders. As they say, the proof is in the eating of the pudding.

As the diary opens Davies is still managing the family owned Examiner. However, he’s growing weary of the “obdurate ordinariness’ of small-town provincialism after living in Peterborough for 20 years with wife Brenda and three teenage daughters. In addition to overseeing the newspaper, which he leaves largely to competent subordinate managers, he’s writing reviews for Saturday Night magazine and a weekly literary column for the Toronto Star. He’s also completing a book of literary odds and ends referred to as ‘the Knopfbook,’ subsequently published as A Voice in the Attic. His most recent novel, A Mixture of Frailties, the last volume in what became known as the Salterton Trilogy, was published the previous year to favourable reviews.

His play about Casanova, General Confession, has fallen on barren ground. Nonetheless, he’s collaborating with his theatrical mentor Tyrone Guthrie, the Stratford Festival’s founding artistic director, on a stage adaptation of the Leacock Award-winning Leaven of Malice, the second volume in the Salterton Trilogy. Davis travels to Guthrie’s ‘big but rambling and inconvenient’ country house in Northern Ireland to work on the play which eventually premieres as Love and Libel. He affectionally describes the Guthries as ‘charmers but loonies.’

We spend the first portion of A Celtic Temperament accompanying Davies through the interminable trials and tribulations of transforming the comic novel into a play before flopping when it finally opens in New York, via Detroit and Boston.

Although the theatre remained Davies first love and he longed to succeed as a playwright, he nurtured a love-hate relationship with his creative muse. ‘For twenty years,’ he reflects, ‘I have been a writer, and never before have I been in a milieu where every consideration came before literary considerations, and the opinion of anybody — the humblest actor, money counter or baggage man — weighted equally or heavier than that of the author. My disgust is like a cap of fire bearing down on my head. Why would an author of any pride submit to the impertinences of theatre people?’

The second portion of the diary is devoted to Davies’ transition from newspaperman/playwright/novelist to Master of Massey College.

We follow him as he negotiates the treacherous waters between the eccentrically wealthy Massey family and the arcane labyrinthine academic politics at the University of Toronto. We learn that Davies was held in condescending suspicion, if not jealous contempt, by many in the cloistered academic fraternity who viewed the writer as an intellectual interloper. Davies was not without his own doubts — ‘. . . in the academic world which I am by no means qualified,’ he writes, ‘I can easily become an ornamental hermit, or a lodging-house keeper, or an inferior pedant.’

These two narrative threads unfold like a British novel of manners — equal parts Evelyn Waugh and P.G. Wodehouse — with a Canadian twist. Meanwhile, the writer who emerges is far from the persona he honed over his public career as Edwardian Man of Letters combined with magisterial Northern Magus. Ambitious and restless, with a Protestant work ethic under which most would falter, he simmers with frustration, anxiety and uncertainty as to his stature as a serious writer.

We learn that Davies succumbed regularly to the black dog of depression. ‘My trouble is that I do not know anything about anything thoroughly, and am ignorant, superstitious, spiteful and third-rate,’ he writes. An intensely shy introvert behind his mask of flamboyant self-esteem, he often exhibits a revulsion towards people, while enjoying good food and drink and enthusiastically collecting expensive objects including books, theatre memorabilia, antiques, records and art works. His love of film and music is surpassed only by his love of literature. We also learn of his sundry ailments including his suffering from roctalgia fugal, a deep pain in the rectum that feels like a severe muscle cramp that usually flares up at night.

The diary brims with observations about literary matters. He dismisses Marcel Proust as ‘a brilliant bore.’

Similarly he has nothing kind to say about the writers vying for the 1960 Governor General’s literary award which he was adjudicating, won by Brian Moore for Luck of Ginger Coffey. He scorns the list as ‘a dreary lot. I’m out of love with Canada these days,’ he writes, sounding like Conrad Black, ‘a country of stupid, ill-educated, timid, narrow-gutted Scotchmen.’ He then describes The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, a picturesque comedy written by Mordecai Richler, a Montreal Jew, as ‘a derivative and ill-planned book.’

Is it any wonder that the national literary award erred in not awarding the prize to Davies for Fifth Business in 1970, only to concede its foolish mistake by giving the prize to him two years later for The Manticore, a much inferior novel?

It was during this period that Davies abandons Sigmund Freud for Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, who was to have a lasting influence on his fiction, through the Deptford and Cornish trilogies and his final novel The Cunning Man. He even flirted with the idea of undergoing psychoanalysis with M Esther Harding, a leading Jungian based in New York City.

As delightfully insightful and infectiously entertaining as A Celtic Temperament is, I do have a couple of quibbles. First, nothing is gained by the inclusion of a handful of letters to Brenda (addressed as Pink or Pinkie). We know from the diary how much he loved his Australian wife, whom he met at the Old Vic, not to mention how much he adored his daughters. His saccharine letters only repeat what we learn from the diary. The unnecessary inclusion is perhaps explained by the fact that his middle daughter and literary executor Jennifer Surridge edited the volume with Ramsay Derry, a family friend who was an editor at Macmillan of Canada when Davies’ most accomplished books were published.

The other quibble is the inclusion of what I take is a boxscore of his sexual relations with his wife. I’m far from prudish in matters of amour; however, we gain little insight into Davies the lover when he cryptically refers to enjoying ‘h.t.d.’ 79 times in 1959, variously described as ‘most refreshing. . . splendid. . . fierce. . . very good. . . fine. . . admirable. . . excellent. . . unforeseen and delightful. . .’ and finally ‘best in many months.’

More enlightening are his comments on sexual intimacy — ‘I have never desired or sought physical intimacy with a woman I did not love and do not think I could have borne it if I had. Now, I am sure I could not perform. Have never been given to lust, and copulation without love is no more.’ — and pornography — ‘Brenda and I agree that one of the signs of true cultivation is an ability to talk and write of sexual and scatological things with some grace. . . and not with vulgar gloating or tumescent solemnity.’

We now have the publication of Davies’ novels, plays, essays, letters, lectures and conversations about the writer, not to mention Judith Skelton Grant’s monumental biography and rich assortment of criticism. Publication of the diaries provides the finishing brushstrokes in the fullest portrait of a Canadian writer ever painted in this country. Based on the manifold strength of the multifarious publications it’s difficult not to view Davies as the most significant Canadian writer of the 20th century — with apologies to Alice and Margaret and anyone else you care to mention.

In addition to whatever diaries are published, Trent University is publishing Davies’ complete diaries in digital format, edited by professor emeritus James Neufeld. Affiliated with the Editing Modernism in Canada project, the target date for release of the online edition is 2017.