I imagine this midnight moment’s forest:

Something else is alive

Beside the clock’s loneliness

And this blank page where my fingers move.

— The Thought-Fox

Ted Hughes wrote with his penis as much as with his fountain pen. It was both his greatest strength and his greatest weakness, which cast the English poet in the schizoid role of both tormented figure of classic mythology and Shakespearean tragic hero.

The women in his romantically complicated life are so inextricably entwined with his writing — journals, diaries and criticism as well as poetry and translations — that it’s impossible to untangle the two.

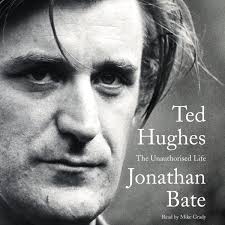

This is the inescapable conclusion a reader reaches after completing Ted Hughes: The Unauthorized Life, the 662-page biography written by English literary critic Jonathan Bate and published by HarperCollins.

Bate would appear to be the ideal biographer for Hughes because of shared literary and ecological interests. He has written studies of the two writers who most influenced Hughes: Shakespeare (Soul of the Age, The Genius of Shakespeare, Shakespeare and the English Romantic Imagination and Shakespeare and Ovid, among others) and Wordsworth (Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition). As well, he has written an innovative study on ‘ecopoetics’ titled The Song of the Earth. In the latter study, Bate describes Hughes accurately and evocatively as ‘a truly feral poet, scavenging like a fox on the margins of urban modernity. His poetry has the hot stink of animal flesh. . . [he] embarked on an energized, vertiginous linguistic drive back to raw nature.’

Sadly, the controversy that dogged Hughes throughout his life outpaces his death in 1998 at the age of 68, seriously compromising what, nonetheless, remains the most substantial biography to date. The result is that Ted Hughes: The Unauthorized Life is not as good as it otherwise would’ve been and should’ve been.

The trouble stems from Hughes’ widow Carol, who is caretaker of her husband’s estate. Bate had the estate’s blessing in 2010 when he began five years of research, only to have its support withdrawn in 2014.

Bate’s scrupulously judicious and lucid biography has come under attack from the estate for alleged ‘offensive’ errors. The book’s publisher responded with accusations that the estate’s claims are ‘defamatory.’ The bio has since been shortlisted for the prestigious Samuel Johnson prize for non-fiction.

Based on what I have read of the estate’s allegations, they seem both petty and petulant. I suspect the attack is based on Bate’s deliciously salacious revelations of Hughes’ serial infidelity which spanned his Cambridge years through his death. Simply stated, at no time in his life was a single woman enough to satisfy the poet’s insatiable sexual appetite. Fevered visions of Emily Bronte’s mercurial Heathcliff and Lord Byron dance like sex-crazed sugarplums throughout the bio.

Bate speculates that the source of Hughes’ constant and continuous infidelity was his failure to deal with the circumstances and aftermath of the February 1963 suicide of Sylvia Plath — his true and abiding love and soulmate. While this doesn’t convincingly explain the poet’s need for concurrent sexual partners, it’s easy to agree with Bate’s assertion that Plath cast a dark shadow over the full length of Hughes’ life and art. Indeed it’s tempting to conjecture what his life and art would have been had he never met Plath.

Bate is the first biographer to have access to Hughes’ voluminous manuscripts, including journals, letters and extensive literary drafts, housed at Emory University, in Atlanta, Georgia, and at the British Library. It’ll be fascinating to see how subsequent biographers interpret this material, especially when sufficient time passes to put in perspective the incendiary feminist backlash that hounded Hughes after Plath’s suicide, not to mention the subsequent suicide of Assia Wevill who killed herself along with the daughter she had by Hughes.

Bate tries valiantly to evaluate Hughes’ literary output, spanning poetry, translations, children’s literature, anthology work, criticism and fiction; but his interpretative hands are tied because of the limitations the estate placed on his right to quote primary source material. This is unfortunate because, as already indicated, Bate was the literary scholar to do the job.

Pertaining to Hughes’ literary legacy, Bate argues that his early collections, The Hawk in the Rain and Lupercal, were his best. His late translations, including Tales of Ovid, were excellent. He traces the poet’s development from mythopoeic poet deeply influenced by Robert Graves The White Goddess through pastoral poet (Moortown Diary, Remains of Element and River) to confessional poet (Birthday Letters).

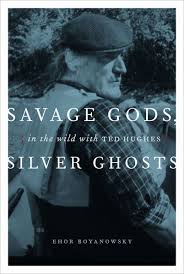

Bate suggests that as Hughes grew older his sexual passion was subordinated to his passion for fly fishing. After being appointed Poet Laureate, one of his favourite angling companions was none other than the Queen Mother. Hughes visited Canada’s West Coast on numerous occasions to fly fish and to visit his fly fishing son who lived in Alaska. In 2009 Ehor Boyanowsky published Savage Gods, Silver Ghosts, a memoir Bate describes as ‘flamboyant if occasionally unreliable.’ Following are excerpts of the review of the tribute to angling companionship I wrote soon after it was published:

Hughes was an avid conservationist and enthusiastic fly angler. He came to love fly fishing for salmon and steelhead in British Columbia after befriending Boyanowsky, a criminal psychologist and professor at Simon Fraser University.

In his book Savage Gods, Silver Ghosts: In the Wild with Ted Hughes, published by Douglas & McIntyre, Boyanowsky offers a charming portrait that traces his relationship with ‘my dear and great friend.’

The volume paints a picture of the poet as ‘a good, kind man,’ which contrasts with the popular media image painted by radical feminists after Plath committed suicide. With the exception of Ezra Pound, no poet in the 20th century was more vilified. As the survivor of a controversial literary marriage, Hughes was condemned by those who blamed him for Plath’s death. That he continued to write poetry, children’s books, verse translations and literary criticism is a testament to his fierce commitment to literature, which was acknowledged in 1984 when he was appointed poet laureate.

Plath is seldom mentioned in Savage Gods, Silver Ghosts. Instead, we get lots of talk about the joys of fly fishing for salmon and steelhead. Hughes was captivated by British Columbia and its rivers, especially the Dean, one of the world’s great steelhead rivers. Boyanowsky describes his friend as ‘one of those true anglers: not the best caster, not a fly tier, not a rod techie, not even an aggressive wader, but someone who will catch fish if anyone can. A fish hawk.’

Hughes was one of the 20th century’s supreme poets of nature who gave expression to the savages that tear ‘tooth and claw’ at the human heart. Boyanowsky depicts his friend as a committed conservationist, a man who defended the natural world with an eloquence befitting a great poet.

This is a small book that pays tribute to a larger-than-life man. It’s the literary equivalent of a good day on the water when the line between fishing and poetry vanishes in the shimmering moment as a wild fish breaks the surface of a deep pool. Let us all be fish hawks.

Keith Sagar, author of Ted Hughes and Nature: Terror and Exultation, argues that River is not only the poet’s finest collection but ‘one of the great books of world literature.’ That Morning, the collection’s concluding poem, ends:

Then for a sign that we were where we were

Two gold bears came down and swam like men

Beside us. And dived like children.

And stood in deep water as on a throne

Eating pierced salmon off their talons.

So we found the end of our journey.

So we stood, alive in the river of light

Among the creatures of light, creatures of light.

Sagar observes, rightly I believe, that the poem expresses a vision of ‘divine harmony of matter and spirit, as if this were no longer a fallen world. . . Nature is not clothed in celestial light, has no need of any borrowed glory. It is wholly contained of earthly light, which is none the less spirit.’