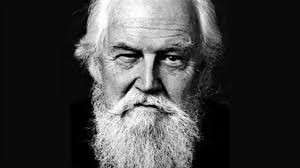

Twenty years ago Canada lost one of its great writers: Robertson Davies. I offer these recollections and reflections with a merry heart on the anniversary of his passing and acknowledge the release of the captivatingly engaging first volume of his selected diaries under the evocative title of A Celtic Temperament.

The first book I ever read that wasn’t mandatory school reading was Fifth Business. It set me on a path I’ve followed ever since. With Davies’ death, at the age of 82 on December 2, 1995, Canada became imaginatively and creatively diminished. I celebrate Davies’ life and honour his writing not only for his novels, plays, essays, literary criticism, speeches, lectures, ghost stories, letters and journalism, not to mention fictional diaries (under the pseudonym of Samuel Marchbanks) and, now, personal diaries, but for the world of wonders he invited me to enter as a university student long ago.

I completed my honours undergraduate degree at Trent University, in Peterborough, the place Davies lived for two decades as publisher and editor of the family owned Examiner. While at Trent I studied Canadian literature under Gordon Roper, Davies’ close friend who read the Deptford Trilogy in manuscript and wrote the first academic paper linking Davies to Swiss psychologist C.G. Jung. Roper took deep delight in teasing us in tutorials about what was in store for readers with the subsequent Deptford instalments — The Manticore and World of Wonders.

I went to graduate school not so much to learn more about literature as to dig deeper into the arcane marvels of the Deptford Trilogy, one of the pinnacles of this country’s literature. As a result of what I came to understand by reading Davies’ writings, I devoted more than four decades to studying the literature, music, visual art and performing arts of Canada. Much of that time was spent as a newspaper journalist, the majority of those as an arts and entertainment reporter.

It’s been a privilege that has enriched and enlarged my life. Studying the arts, especially literature, has not made me a better person, but has given me a better life. Before I went to university, literature was a foreign country unexplored in my youth. I grew up in a house without books, where the sole means of entertainment was television, cable being the big cultural breakthrough. Since my university days, much of what I have done has been connected to books. Had I not discovered Davies, chances are I would not have become a newspaperman.

The most devastating aspect of surviving a house fire 25 years ago was the loss of my library which included 2,000 works of Canadian literature — the majority of which were first editions, many signed by their authors. The first thing I did after my wife and I established a new home was start rebuilding a library. After all, a house is not a home without books. I mention this not to wallow in self-pity, but to illustrate how literature — and, more specifically, how a writer — reaches out and embraces an individual mind, heart and soul. When one enters into a relationship with books anything is possible.

I experienced remnants of the extraordinary when I was writing my master’s thesis at the University of New Brunswick and received a gift from my landlady’s seven-year-old daughter — a small piece of granite that easily fit into the palm of my hand. Anyone who has read Fifth Business, The Manticore or World of Wonders will appreciate its significance. Similarly, although the girl was raised a Protestant, she attended a Catholic school — St. Dunstan’s.

Another strange occurrence happened at graduate school in Fredericton. I was reading books I thought might relate to Davies’ work when I came across Fata Morgana, a fabulist crime novel by William Kozwinkle, who subsequently gained fame and fortune as the author of ET. I knew nothing about the American writer, save my surprise when one day I picked up a volume of Jung’s collected works in the university library, only to discover that the last person to check out the volume was none other than William Kozwinkle. I later learned he had been living in rural New Brunswick at the time. I surreptitiously slipped the library card into my pocket, replicating the actions of Dustan Ramsay in Fifth Business.

I had one recurring nightmare while in Fredericton, that of losing my thesis in a house fire. Although the fire came 15 years later in a distant city — Kitchener — it erupted in an apartment that had been occupied by a family that had just moved to Ontario from, you guessed it, New Brunswick. A scorched leather-bound copy of my thesis was one of the few books to survive.

These threads of personal history might seem self-indulgent, but I assure you Davies would appreciate the synchronicity. For he viewed the world through a sympathetic creative vision where the marvellous and the miraculous co-exist with the commonplace and the everyday.

Books are not for everyone. You can live a fulfilling, productive and worthwhile life without reading. But discovering a writer who speaks to you personally is an enduring gift. Like the strongest friendships, it’s a gift for life.

Around 1989 I had the privilege of interviewing Davies late one afternoon between public readings in Waterloo. There was so much I wanted to say, but the words of gratitude never came. Although he complained of tired hands, the result of signing books while on a lengthy promotional tour, he graciously signed ALL of my first editions without complaint, even though his wife Brenda was not pleased. These perished in the aforementioned fire. I reacquired the Davies canon, sans autograph.

I continue to remember 1995 not only as the year Robertson Davies died, but as the year our second son was born in June, the same month I was born. We named him Robertson.

I now beg your indulgence to set the record straight by challenging an impression Davies expressed in one of his letters with respect to Fifth Business. In a 1984 letter to Roper he reveals his frustration with academic critics. ‘One of the things that astonishes me is that these critics are aware that the whole book is an extended letter to the Headmaster, but it never occurs to them that the Headmaster might be anyone other than the chief executive of Colborne College,’ he complains to his old friend. ‘They never think that Ramsay writes it on what he thinks may be his death-bed. Luckily the books have readers who are not academics, and who just treat them as novels.’

Happily I fall into the latter category. But in my closest brush with academia — my master’s thesis, published in 1980 and titled Robertson Davies Deptford Trilogy: A Quest Romance — I conclude my chapter on Fifth Business with a question related to Ramsay’s final words to the Headmaster — who he refers to as the ‘one man’ — about ‘the sources from which my larger life was nourished.’ In my thesis I speculate: ‘Could it be that the ‘one man’ — the only One who need know about such things — is God Himself, that final arbiter residing over the folly and nobility of man