It was a winter like no other, at least in my lifetime, one year shy of three score and ten. Not since the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918 had the world been in the clutches of such a pernicious pandemic as the coronavirus of late 2019 and 2020. People around the world were sick and dying, medical resources were stretched to the limit, friends and families were separated and isolated. Economies tanked as governments locked down countries—including Canada, Britain and the United States—in a desperate endeavour to contain the virus. Fear, anxiety and uncertainty disrupted the social order, as emotional and psychological fabrics frayed.

The opening of trout season on the last Saturday of April is traditionally a coming-out party for fly anglers across southwestern Ontario who resemble school children released at recess. This year the pandemic heightened expectations. Although the province was shut down by government fiat, the season opened as usual—albeit under unusual conditions. Parks and conservation areas were closed, as were marinas, boat launches and public access points to recreational water. Strategies to ‘flatten the curve’ of pandemic infections and deaths, such as social distancing, remained in effect.

Still I was eager to get out on the water for no other reason than to assert a semblance of normality. I yearned for the familiar, the ordinary, the commonplace. Even the uncertainty of catching a trout was reassuring. There is something about moving water and the rhythms of casting a bamboo fly rod that relaxes the body, soothes the mind and comforts the soul. John Burroughs, one of America’s most celebrated nature writers, recognized the ‘salutary ministrations’ of water and angling. In his essay ‘Speckled Trout,’ published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1870, he writes:

I have been a seeker of trout from my boyhood, and on all the expeditions in which this fish has been the ostensible purpose I have brought home more game than my creel showed. In fact, in my mature years I find I got more of nature into me, more of the woods, the wild, nearer to bird and beast, while threading my native streams for trout, than in almost any other way.

A fews days after the season opened my fly angling buddy Dan Kennaley and I were bound for the headwaters of the Saugeen River. A mere ninety-minute drive from my home in Waterloo, it is one of my favourite places on our ‘good green earth’ (the phrase is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s in Braiding Sweetgrass).

Although I enjoy fishing from a canoe on tranquil northern lakes, I cherish wading rivers. There is something magical about fishing in water that flows forever onwards from place to place and around the next bend ripe with the potential for wonder. The sense of freshwater motion is hypnotic and therapeutic, as my metabolism fuses with a force greater than myself. In syncopation with the rhythms of flowing water I am transported out of my subjective body into an awareness of the objective natural world, of which I am an integral part. Through imaginative sympathy I become river.

When this mysterious transfiguration occurs, a river not only acts as a backdrop or setting, it assumes a role in an unfolding narrative. For my part, I am not a player on the stage of nature but an active participant in the drama of Creation.

Similarly, although I regularly fish the tailwater of the Grand River, I much prefer headwaters in all their riparian splendour. Here the mystery is deeper, darker, more profound. Ted Williams—not the Boston Red Sox legend but the freelance journalist who wrote about outdoor sports and conservation for such magazines as Audubon and Gray’s Sporting Journal—referred to fishing such ‘secret, timeless’ places as ‘rivertop trouting.’ (I love the phrase.)

Dan and I met in the village of Arthur, but breaking with our habit of loading our gear and ourselves into one vehicle—during which we routinely engage in our deepest conversations—we drove separately to our destination on the Rocky Saugeen.

We arrived mid-afternoon to a location we had not fished for at least three years. It felt good to be back. I last visited the rugged stretch with my youngest son, Robertson, and caught a half dozen brownies and rainbows within half an hour of leaving for home at 6 pm. This proved my most memorable outing on the Rocky.

It was a lovely day, featuring a warm invigorating sun and deep azure skies with minimal cloud cover. Sunlight can be an angler’s foil, but in spring it is less troublesome, especially in the midst of afternoon mayfly hatches. While we were gearing up at the shoulder of the gravel road, a conservation officer pulled up in a black pickup.

‘Just checking on anglers and turkey hunters,’ he said.

‘I don’t have a fishing licence because I’m riding in the backseat of sixty-five,’ I offered. ‘But I have my driver’s licence.’

He chuckled. One of the few benefits of growing old is not having to purchase a fishing licence in my home province of Ontario.

‘Good luck, gentlemen, and stay safe,’ he said before driving off.

As we made our way down a steep bank to the river we were greeted by a couple of kingfishers rattling from tree to tree. I chose to interpret the unscheduled meeting as a fortuitous omen. In contrast to some anglers, I am not especially superstitious, but it seems unduly foolhardy not to embrace Lady Luck when she comes calling in the guise of a pair of winged fingerling marauders.

The water was a tad high and fast. Since we hadn’t had rain in the past few days, we credited the roiling water conditions to the runoff of recalcitrant snow overstaying its welcome in thick bush.

Dan and I both tossed black wooly worms with short red tails downstream and across. I caught three lusty brown trout between seven and nine inches, before switching to a Hendrickson emerger and getting a solid hit which I was unable to set. Dan caught one brownie after I left for home, which saved him from the pungent fragrance of skunk which lingers long after an angler retires from the river–with his rod tucked firmly between his legs.

• • • • • •

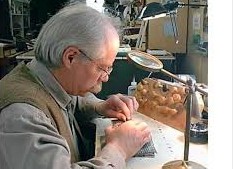

Later in the week I drove to Clifford to join up with Wesley Bates, the artist with whom I worked on our fly angling book Casting into Mystery. Respecting social distancing, I remained in my Jeep while following him in his car to a provincial highway, then I took the lead en route to the Rocky.

As I was driving I noticed a full moon floating faintly over the centre of the gravel road high in the clear blue sky. I thought of the lunar phantom as a fellow wayfarer guiding me to the pot of piscine gold at the end of the aquatic rainbow. Of course, seeing the moon during the day is not exceptional. Still I am always intrigued by the occurrence, especially in relation to fishing.

My fascination with the moon goes back to early childhood. I remember laying across the back window of my dad’s Plymouth V8 sedan when he was driving my mom, brother and sister home after an evening out, usually visiting friends or relatives. As I remember it, stars were always winking at me from a canopy of deep darkness. Looking back, I can say with absolute certainty that I never felt safer and more secure as the moon seemed to follow my family home as I snuggled under a quilt of imminent slumber.

I do not put much stock in newspaper horoscopes, but as someone who takes seriously the wisdom tradition of the ancient Celts, I cannot dismiss the significance of the stars and the planets, the days and the elements, under which a person is born. Born under the Northern cardinal sign of Cancer, which is associated with water and ruled by the moon, I have always felt an intuitive, emotional pull toward both natural forces.

The moon has long been associated with water. Both are feminine symbols representing the rhythm of time as embodied and enacted in natural cycles. Moreover, both moon and water are connected to fish and fishing. Unlike many anglers, I never fish in accordance with monthly lunar tables. Getting out on the water whenever possible has always been more important than increasing the probability of catching fish. Still I cannot resist falling under the enchanting triune spell of moon, water and fish contained within the mystery of fly angling. If I remain more of a romantic than a technician, so be it.

Wesley was taken in by the raw beauty of the stretch of river he was experiencing for the first time. I gave him a black woolly worm and we spent the afternoon casting downstream and across—to no avail as it turned out. We both had a couple of strikes, enough to excite expectations, but our piscatorial courtships ended in rejection. If comparing angling to courting strikes some readers as antiquated, I defer to no less an authority than John Burroughs who likens a stream to a paramour in ‘Speckled Trout’:

Then what acquaintance [an angler] makes with a stream. He addresses himself to it as a lover to his mistress; he wooes (sic) it and stays with it till he knows its most hidden secrets. It runs through his thoughts not less than through its banks there; he feels the fret and the thrust of every bar and boulder. Where it deepens, his purpose deepens; where it is shallow, he is indifferent. He knows how to interpret its every glance and dimple; its beauty haunts him for days.

Admittedly wooing might sound outdated, if not silly, in terms of contemporary vernacular. However, considering its connotation of something that puts people in danger of making fools of themselves, the word certainly applies to fly fishing.

True to angling form I made a beeline to the very spot—under identical conditions at the same time of day with the same fly—I caught the trio of vibrant brownies a few days previously. But this time, nothing, zilch, nada. I am constantly amazed, and sometimes more than a little frustrated, by this eternal fact: fish are not always where they are expected to be, even supposed to be, at least according to an angler’s best judgment.

A few hundred metres downriver from where I was casting hopelessly, a quartet of turkey vultures slowly circled what I suspected was some sort of appetizing carrion far below. I knew they were adults because of the grey flight feathers under their long, broad wings.

I view these familiar raptors as totems for fly anglers. You would be hard pressed to find homelier creatures. Yet when they are in their element, floating effortlessly on a cushion of air, they are as graceful and as elegant as a bushy Elk Hair Caddis dry fly floating on a cushion of current. If I were to confess that I aspire to cast like a turkey vulture, I would not mean it in any disparaging or derogatory sense.

As is our custom, we hapless pair of spurned anglers ended our outing by sitting on the bankside—that magical thin place between earth and water which the Celts revered as sacred because it is where the barrier between the earthly realm and the spiritual realm is thinnest. I poured ruby tinged hues of liquid amber from a flask into a couple of stainless steel ‘shot glasses’.

Matured for twelve years in American bourbon and Spanish sherry oak casts to achieve a delectable balance of Christmas fruit, vanilla and spice, Abelour remains one of my favourite Speyside malt whiskies. (Confession: despite diligent effort spanning five decades, I have yet to find a single malt I disliked.)

We savoured the drams as our talk drifted towards the pandemic. Wesley admitted he had been feeling out of sorts lately.

‘I’ve felt back-watered or eddied working in my studio and trying to keep my focus which is always being challenged by the flotsam of life. Not unique, I know, but very distracting and frustrating. I really needed these few hours on the river.’

‘I like your description of ennui which is both accurate and poetic,’ I replied. ‘I was wrestling with motivation during the past few weeks. Writing became a challenge.

‘The interesting thing is, the creative juices started flowing after Dan and I got out on the water. It was as if a tap had been turned on. You know, when you open an outside faucet after hooking up the garden hose in the spring.’

Many commentators have acknowledged the similarities between making art and fly fishing. So it wasn’t surprising that a writer and an artist who share a passion for fly fishing felt disjointed in troubling times as our beleaguered planet seemed precariously off kilter.