‘So get down on the highway

You foolish one

You’re going to be feel so bad

When your best friend’s gone’

— Lonely One Car Funerals

On a cold February in 2008 Canadian music lost one of its most beloved songwriters.

William Patrick Bennett died from a massive heart attack February 15 at his home in Peterborough, Ontario. He was 56.

While not as well known as he deserved to be in the eyes of those who revered him — including me — Willie P. Bennett’s gifts as a songwriter were celebrated by loyal fans and musical peers for more than 35 years. Like Stompin’ Tom Connors, he was a true, homegrown legend–a Canadian hero.

Bennett had suffered a heart attack the previous Victoria Day weekend while performing in Midland with Fred Eaglesmith. Bennett was a founding member of Eaglesmith’s Flyin’ Squirrels in 1995. He had fully recovered and was back performing as a solo artist — he played three dates the previous month — yet had not joined Eaglesmith on tour.

On February 28 he was to make his fourth appearance since 1986 at Waterloo’s Original Princess Cinema. The original concert was cancelled; however, Princess owner John Tutt arranged a tribute concert in its place.

I’ve been a staunch Bennett fan since the early 1970s. I saw him perform solo in raucous university pubs (including Trent University’s student pub The Commoner) and grungy bars (including London’s Talbot Inn), with the Dixie Flyers bluegrass band and with Eaglesmith on numerous occasions. I enjoyed the privilege of reviewing his concerts and his albums many times.

I recall seeing Bennett in 1975 at the Home County Music & Art festival. At the time, he was part of a flourishing folk scene in the city — encompassing Stan and Garnet Rogers, Doug McArthur and David Bradstreet, among others — that revolved around Smale’s Pace coffeehouse. He infamously had spent time living in Stan Roger’s closet in a house on Maitland Street, perhaps the appropriate resting place for a notorious party animal. I once asked Bennett about his formative years and he replied with an elfish grin, ‘I don’t remember much of the 70s.’

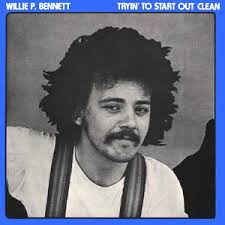

Bennett was performing at Home County — the annual music festival held in London’s downtown Victoria Park — and he had just received a mock-up of the cover of his debut album Startin’ Out Clean. He was all smiles when he showed it to his mom who happened to be sitting in the audience in front of me. The fresh-faced artist thought the cover was wonderful. Of course, it really wasn’t wonderful. It was amateurish, tacky even, a cut-out of Bennett against a drab bluish grey background.

But, as they say, you can’t judge an album by its cover. The dozen songs were — and remain — classics: White Line, Music in Your Eyes, Down to the Water, among others. Released in 1975, it is the first of two folk masterworks released in the 1970s on David Essig’s Woodshed Records, including Hobo’s Taunt (1977) — which squeaked in at No 95 on the Top 100 Canadian Albums. The other masterwork is Blackie and the Rodeo King (1978).

Few Canadian albums boast as many superb songs as Hobo’s Taunt: Come On Train, Lace and Pretty Flowers, Storm Clouds, Stealin’ Away, A Woman Never Knows, Lonely One Car Funerals, If You Had to Choose, You, Faces and the title track. Nary a weak track in the bunch.

Although he released other albums sporadically over the next couple of decades — including The Lucky Ones (1989), Collectibles (1991), Take My Own Advice (1993) and the star-studded, Juno-winning Heartstring (1998) — Bennett’s reputation as a master songwriter rests on his first three albums. Like the poets John Keats, Dylan Thomas and Leonard Cohen (before becoming a balladeer), Bennett wrote his best songs when barely out of his teens, when artistic inspiration burned bright and bold like a comet in the night sky.

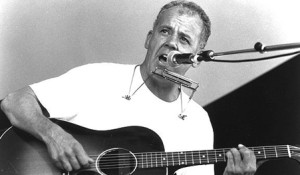

Born in Toronto in 1951, Bennett started writing in 1966, while still in his teens. Amazingly, he wrote White Line a mere three years later. From the outset he maintained a pattern of balancing a solo career with performing in a band, first playing harmonica with the Dixie Flyers during most of the 1970s.

Bennett was Eaglesmith’s full-time sideman on harmonica and mandolin, which he learned as a birthday gift to himself when he turned 40. He accompanied Eaglesmith as he transitioned from farm-protest folk obscurity to Juno-winning alt-country heavyweight.

Bennett’s own writing bridged folk, country, acoustic blues and bluegrass — a rich blend that would become known as roots music or Americana. Regardless of genre, his songs are marked by a searing emotional honesty that pierces the most life-hardened of hearts. His lyrics read like poetry expressed through a raw, plaintive voice devoid of pretence or affectation.

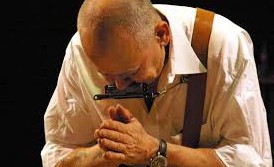

On stage he was sardonic and self-deprecating, as open as a fresh laceration. Whenever he performed at a festival, such as Guelph’s Hillside, he would be invited by other artists to join them on stage on harmonica or mandolin. He always made the musicians he accompanied sound better; not by drawing attention to himself, but by blending into the background, exercising taste and discretion, grace and generosity.

Bennett’s reputation received a shot of artistic adrenalin in 1996 when Colin Linden, Stephen Fearing and Tom Wilson released High and Hurtin’, a tribute album to their songwriting hero. They called themselves Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, and what began as a one-off project expanded to a folk-rock supergroup, built on eight critically acclaimed albums since 1996. The group has covered close to 25 of Bennett’s songs.

This wasn’t the first time Bennett had been recorded by others. David Wiffen, Stan and Garnet Rogers, Colleen Peterson, Prairie Oyster, Pure Prairie League and Emmylou Harris, among many others, honoured him with fine covers. As fate would have it, Bennett was recording a new album with Winnipeg’s alt-bluegrass outfit The D Rangers before he died. He was expected to perform new material at the Princess.

We’ll understand it all in time

— from Music in Your Eyes

Bennett was nothing if not a consummate professional. When he had his initial heart attack in 2007 while playing with Eaglesmith, he completed the set before seeking medical intervention.

The show must go on is a motto he followed, whether performing in rowdy beer joints, acoustically friendly concert halls or under tranquil stars at summer music festivals.

Although his death sent shock waves through the Canadian music community, stunning performers and patrons alike, Bennett would understood in his usual self-deprecating way John Tutt’s determination to pay homage with a tribute concert. The Princess Cinemas co-owner spoke for thousands when he confided, ‘It’s terribly sad news,’ adding he would arrange ‘a gathering of friends.’

‘That night was Willie’s,’ Tutt observed with respect to the original concert. ‘The night is going ahead in his absence.’ It was a testament to Bennett, both the man and the artist, that musical friends responded immediately to Tutt’s invitation. ‘We don’t have a huge roster, but given the timing and musicians’ hectic schedules, whatever little we can do is better than nothing.’

A feeling of love permeated the Original Princess on the evening before his originally scheduled concert was to take place, as performers and fans alike gathered to celebrate Bennett’s life, music and legacy of songwriting excellence.

Everyone knew Bennett was scheduled to return to the Princess. The fact that his heart betrayed him was sad beyond words, but not surprising. For, if there was one word to define the man and the artist, it was heart.

Just ask the capacity crowd of fans and musical peers who gathered to remember through song and story the man who was loved and revered. Thanks Willie,’ Princess co-owner Wendy Guymer affirmed after welcoming everyone. ‘This one’s for you.’

The first set featured Scott Bradshaw, who had opened for Bennett at the Princess way back in 1986. He kicked off the evening with Willie’s Diamond Joe.

Sneezy Waters and Ian Tamblyn, two veteran singer/songwriters who met Bennett in the early 70s, drove in from Ottawa. Waters, who is best known for portraying Hank Williams in The Show He Never Gave, was instrumental in introducing Bennett’s songs to Ottawa’s emerging folk scene four decades earlier. He demonstrated how much space there is to move around in Bennett songs with highly personal takes on Don’t Have Much to Say and If You Have to Choose.

Tamblyn opened with Winter Soldiers, a song he wrote for Bennett in 1990 after his friend travelled to Ottawa only to discover upon arrival that the venue where he was to perform had closed. ‘It was a time when there weren’t a lot of jobs for guys like us,’ Tamblyn recalled. He concluded with a heartfelt The Lucky Ones.

Next up were two musicians who played with Bennett in the Dixie Flyers. Dobro ace Al Widmeyer was joined by stand-up bassist Brian Abbey, a founding member of the Flyers. Widmeyer, who lives in Kitchener, offered a fine version of This Lonesome Feelin’, a Bennett song he performed while touring with Stompin’ Tom.

Abbey (who I met in the early 1980s when he coached the St. Thomas Stars Junior B hockey team) might not be a natural lead vocalist, but he sings with the raw soul of an untutored musician from the Appalachian Mountains. ‘Every note I play from now on goes out to Billie, he asserted, using his nickname for Bennett. ‘He was like my other brother.’ Abbey’s renditions of For the Sake of a Dollar and Me and Molly — ‘my mother loved this song,’ he confided — were heart-wrenching. ‘I love you, Billie,’ he said after singing the final line of Me and Molly about ‘the bitter end of summer . . . dying.’ Bennett lived with Abbey’s parents in Belmont, Ont. for a couple of years in the 70s and Abbey still had the Martin guitar — the very guitar on which Bennett wrote many of his greatest songs — the songwriter had swapped for an amp.

The second set featured Fearing; Jay Linden, the elder brother of Colin; Dan Walsh, who played with Bennett for five years in the Flying Squirrels; and then-Fergus-based singer/songwriter Nonie Thompson (known at the time as Nonie Crete).

If you were keeping track, which no one was inclined to do, Fearing would have stolen the show through sheer stage prowess. He said he was introduced to Hobo’s Taunt when he began playing the guitar at the age of 14 while living in Dublin, Ireland.

He noted Bennett’s songs were easy to learn — ‘three chords and the truth’ — but difficult to understand. He delivered moving readings of Faces, Happy on the Moon (which he ‘had the pleasure of first hearing Willie sing on my deck’), Blackie and the Rodeo King and Startin’ Out Clean. Fearing added that Bennett introduced him to country music and maple butter. ‘I’ve read comparisons of Willie to peers such as Stan Rogers, but he should be compared to Townes Van Zandt and Muddy Waters. He’s at that very high level.’ I agree with Fearing’s assessment of Bennett’s art.

Linden, who knew Bennett before he recorded his first album in 1975, started with Music in Your Eyes.

Thompson, who first met Bennett at the Hillside Festival in 1994, said she still had a guitar string she changed for him during a workshop. ‘He’s the reason I started playing the harmonica,’ she confessed. She did one Bennett song (Brave Wings), augmented with original songs written in honour of her grandfather, mother and the Grand River.

Walsh was content to provide brooding atmospheric background music on dobro. He announced that a memorial service was planned for March in Peterborough, with music to follow at the Knights of Columbus — Bennett would approve of the venue. The Princess concert was the first of numerous memorial concerts that took place over the following weeks in honour one of our great songwriters.

Bennett has not been forgotten. Essig, producer of Bennett’s first two albums, paid tribute to his old friend with Willie P, a song released on the 2009 album Double Vision. Alberta-based country artist Corb Lund wrote It’s Hard to Keep a White Shirt Clean, a song for Bennett on his 2009 album Losin’ Lately Gambler. In 2014 the Willie P. Bennett Legacy Project was launched online, providing a space to share stories and new versions of Bennett songs, as well as initiate a memorial award in his honour.

In 2010 Bennett was inducted into the Canadian Country Music Hall of Honour. But many fans agree with Abbey that his brother-in-music belongs in the Canadian Songwriters’ Hall of Fame. Willie P. has my vote.

I have many fine memories of Bennett performing. One of the strongest was documented in a Waterloo Region Record review I wrote in October 2003:

How do you improve on a masterpiece?

You do what acclaimed Canadian singer-songwriter Willie P. Bennett did Friday night when he kicked off the annual Canadian Songwriters’ Festival.

He performed one masterpiece, Music in Your Eyes, then he stepped away from the microphone, walked to the edge of the River Run Centre stage, started strumming his mandolin and launched into White Line:

‘Cold and lonely on the road

Lord, I wish I had a hole to climb in. . . .’

It was one of the most electrifying moments in the festival’s five-year history and the audience hung on every single heart-aching word.

After the concert I saw Bennett sharing a few pints with some musical cronies, including songwriter/producer Scott Merritt, in a local watering hole. I had known Merritt since meeting him in his hometown of Brantford in 1983. Like Bennett, he has talent enough to be a household name — but isn’t. I said hello to him and turned to Bennett and said: ‘You were the best when I first saw you in the 1970s and you are still the best, Willie.’ I never spoke truer words–words I stand by today.