Tom Thomson went missing on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917. His body was recovered on July 16, 1917. To commemorate the centenary of the death of one of Canada’s great national icons, I will post a blog each day from July 8, 2017 through July 16, 2017 devoted to aspects of the painter’s life, art and legacy. I begin with a review of The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson, an essential read for anyone who wants light shed on the dark mysteries cloaking the painter’s death.

The death of Tom Thomson resembles a ghost story told around a campfire late at night beneath a panoply of stars, with the Northern Lights dancing in the distance beyond a dense enclosure of boreal forest.

Those who believe Canada’s most famous painter died under suspicious circumstances — whether misadventure, foul play or murder — will view Gregory Klages as a killjoy or stick-in-the-mud. In truth he is something of a wet blanket on the embers of conjecture and speculation, fuelled by gossip, rumour, hearsay and innuendo. Ditto for writers who have cashed in by advancing conspiratorial theories based on bad research and lazy scholarship, motivated by self-interest and celebrity. You know who you are.

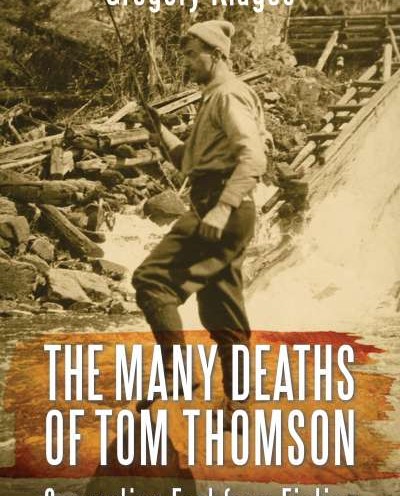

Klages’ The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson is the first book out of the gate — albeit a year prematurely — to commemorate the centenary of the iconic Canadian artist’s death. Aptly subtitled Separating Fact from the Fiction, the book published by Dundurn does exactly that.

No Canadian artist in any field, endeavour or discipline is compromised by biography more than Thomson. It’s impossible to separate his art from his life, especially given the circumstances surrounding his death 99 years ago. Although officially ruled as ‘accidental drowning,’ his death at age 39 remains unexplained and unsolved. Consequently his achievements as one of the country’s most significant artists — including acting as the spiritual guide of the famed Group of Seven — has been eclipsed by the machinery of legend and myth, oiled by a shroud of mystery.

Thomson was last seen on July 8, 1917. Although his abandoned canoe was sighted the next day, his badly decomposed body was not recovered until eight days later floating on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park.

Although there was some dark suspicion surrounding Thomson’s demise, including the possibility of suicide, the spectre of foul play did not break daylight until 1935 when Blodwen Davies self-published A Study of Tom Thomson. Death by misadventure received a shot in the arm in 1970 when Judge William Little published The Tom Thomson Mystery.

Since then the conspiratorial floodgates have opened with virtually every author devoting ink to Thomson’s death advancing a pet theory involving violent misadventure. Art scholar Joan Murray and journalist Roy MacGregor have together built a Tom Thomson cottage industry from the timber of conjecture sans verifiable evidence.

I’ll leave it to readers to discover for themselves the unsubstantiated theories advanced by Murray and MacGregor, not to mention David Silcox, Jim Poling Sr., Neil Lehto, Wayne Larsen, George A. Walker and Larry McCloskey. Likewise, I won’t detail the sober, dispassionate methodology Klages applies to questioning, challenging, testing and ultimately repudiating the claims of foul play, whether murder or manslaughter. Anyone with even a cursory interest in the Thomson mystique will want to read The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson.

Klages is a cultural historian, art critic and practicing artist as well as adjunct professor at York University. His interest in the landscape painter dates back more than a decade to when he was a doctorate student at York. He was part of a group that developed a teaching resource regarding Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History, during which he supervised a website devoted to Thomson — Death on a Painted Lake — that outlined historical evidence and current theories. The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson is an extended version of the website.

Klages’ methodology is as simple as it is reasonable. Carefully and systematically he examines contemporaneous eye witness accounts and archival sources, some of which have become available in the last 15 years, in addition to letters and photographs from the Thomson family. He studies documents related to a request in the 1930s to dig up a gravesite in Algonquin Park and analyzes the documents detailing exhumation of the site in the 1950s, along with subsequent forensic reports.

Finally, he compares and contrasts primary sources to the unsubstantiated claims advanced in writings published in the last half century, spanning art history and criticism, biography, speculative fiction and young adult fiction. Instead of advancing his own pet theory, he casts a cold, clinical eye on the claims, some of which are patently self-serving, of other writers.

So what are Klages’ primary conclusions?

(1) Thomson was neither murdered nor did he commit suicide, but died by accidental drowning.

(2) In the absence of conclusive forensic evidence determining otherwise, Thomson is buried in the family plot at Leith United Church cemetery, north of Owen Sound, in accordance with the wishes of his family at the time of his death.

Klages ends prosaically

: ‘The conclusion that Tom Thomson’s death was due to drowning in a sad accident was received with grief and melancholy. It was not rejected as implausible, as not fitting with the evidence, or as having been arrived at irresponsibly. Based on testimony produced at the time, the most sensible conclusion is that Tom Thomson died accidentally, by drowning.’

I will leave it to readers to discover for themselves what Klages has to say about other intriguing elements that cloak Thomson in mystery. Was he involved in a drunken brawl on the night before he went missing? Was he engaged to Winnifred Trainor? Or to any other woman? Did he father a child by Trainor that sent her packing to Philadelphia?

Admittedly Accident on Canoe Lake won’t sell as many books as Murder on Canoe Lake, even if the sad, unfortunate details of the artist’s death remain forever unexplained and unsolved. Accidental drowning does leave us with an option, however. As we approach the centenary of Thomson’s untimely death let’s discard the fiction and celebrate the fact of his remarkable artistic legacy which has carved such a deep and lasting impression on this country’s heart, mind and soul. It’s time we put Thomson the Myth to rest so we can justly praise Thomson the Artist.

I’ll give the last word to Klages: ‘Acceptance of what the evidence indicates, that Thomson died by accident and not suicide or murder, points to the importance of understanding his painting not through the lens of romantic myth, but as what it was, the rather more mundane, but nonetheless inspiring efforts of a skilled and hard-working artist.’

Which, in the final analysis, makes Tom Thomson a blue-collar hero. I think he would approve of the description.