Early on I decided that fishing would be my way of looking at the world. First it taught me to look at rivers. Lately it has been teaching me how to look at people, myself included.

Fishing should be a ceremony that reaffirms our place in the natural world and helps us resist further estrangement from our origins.

. . . the frontier of angling is no longer either ethical or geographical. The Bible tells us to watch and listen. Something like this suggests what fishing ought to be about: using the ceremony of our sport and passion to arouse greater reverberations within ourselves.

You can’t say enough about fishing. Though the sport of kings, it’s just what the deadbeat ordered.

— quotes by Thomas McGuane

I was reading Thomas McGuane long before I started fly fishing. But when I succumbed to the intensely fulfilling piscatorial passion, the celebrated American writer acquired even more significance, becoming a favourite. The reason for my deepening admiration is his writing about fly angling, for McGuane is one of the very best authors to turn his pen to what he refers to as ‘a calling.’

Recently I came across a video of a talk McGuane gave at Montana State University on the MidCurrent website. I want to share my report of it with readers who don’t get the opportunity to watch the video. Hope you enjoy.

Does fishing mean anything? That’s the kind of question to make any self-respecting angler shake in his waders. Even McGuane. The Montana-based author and avid fly fisherman posed the question during his 2016 Trout & Salmonid Lecture at Montana State University Library, which over two decades has assembled an impressive permanent collection dedicated to fishing.

Born in Michigan, where his longtime friend, the late Jim Harrison, was also born, McGuane has ranched in Montana for close to half a century. He raised cattle and broke champion cutting horses when he wasn’t fishing with friends (Russell Chatham, Richard Brautigan, Guy de la Valdène and Harrison) and some of the world’s best known fly anglers, or writing novels (The Sporting Club, The Bushwacked Piano, Ninety-two in the Shade, Panama, Nobody’s Angel, Something to be Desired, Keep the Change, Nothing But Blue Skies, The Cadence of Grass, Driving on the Rim), short stories (To Skin a Cat, Gallatin Canyon, Crow Fair), screenplays (Rancho Deluxe, 92 in the Shade, The Missouri Breaks, Tom Horn) or non-fiction (Live Water, Some Horses, Upstream: Fly fishing in the American Northwest, Horses).

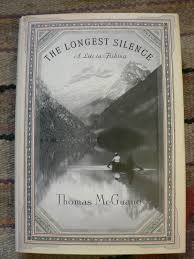

His 1999 fishing memoir The Longest Silence is acknowledged as a contemporary fly angling classic. An Outside Chance, his 1981 collection of sports essays, is equally superb.

Compulsively straightening his notes more than reading from them, McGuane meanders like a freestone creek, ranging over personal anecdote and history, humour and philosophy, ecology and friendship while whittling away at the question that gave his talk its theme. He remains casually conversational, but occasionally references another writer or philosopher, including Henry David Thoreau and Roderick Haig-Brown, Jose Ortega y Gasset, Johan Huizinga and E.O. Wilson.

He confides that, as the lecture date neared, his wife asked him: Do you know the answer? ‘I pretty much stonewalled her on that one,’ he quips with a smile. It was the first of many laughs he provoked from the audience which included A.K. (Archie) Best, fly tying guru and regular fishing companion of John Gierach, and Sweetgrass bamboo fly rod co-founder Glenn Brackett.

McGuane begins his oral meditation from a vantage point of skepticism by questioning fly angling’s therapeutic value. He recalls meeting a group of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. All were suffering from lingering physical and psychological damage and were visiting Montana in an effort to foster healing by learning to fly fish. McGuane concedes he initially dismissed the exercise as ‘a little far-fetched — we’re going to give them a hobby to sort out their problems?’ he quizzes. Although ‘it didn’t seem like a great idea. . . I kept on hearing it was kind of working.’

McGuane’s skepticism melts when he recalls talking to some friends who had similar experiences, including Craig Fellin at Big Hole Lodge in Wise River, Montana. Fellin returned to Montana with horrific war-ravaged memories after serving as a Marine in Vietnam. He carried an ‘inescapable sadness’ and the feeling that ‘everything he loved as a boy was gone.’ Fellin started fishing and caught every single fish in Lolo Creek (in the Missoula area). ’It was the beginning of an aperture for him to see his way back to the life he had before Vietnam,’ McGuane asserts. ‘Without fishing he didn’t think he would have ever gotten there.’

McGuane then casts his memory to his friend Lefty Kreh. One of America’s most famous fisherman and most renowned fly casters, Kreh returned from World War II haunted by memories of the Battle of the Bulge. Kreh returned home ‘pretty psychologically beat up.’ Assigned to a biological warfare center, he got anthrax in his ‘famous casting arm.’ Through fishing, McGuane stresses, Kreh ‘crawled his way back into a fantastic life.’

(To support his examples of fly angling’s therapeutic value, McGuane could have mentioned the Casting for Recovery program that has helped untold breast cancer survivors for a number of years.)

McGuane denies that fishing is either a hobby — ‘it’s more than that’ — or a sport. ‘All of us who fish a lot don’t want anyone to call it a sport.’ Admitting he doesn’t know what to call it, he suggests (with a bemused chuckle) . . . it’s ‘a calling. . . like the priesthood.’

He describes fishing as ‘slow, difficult and personal,’ contrary to a YouTube video he once watched where an angler demonstrating a new technique crowed, ‘I’ve already got 15 outta this hole!’ ‘That doesn’t strike me as spiritual,’ he notes dryly.

McGuane then ponders whether fishing means ‘something more than we normally acknowledge.’ He recalls starting to fish at four years of age with his father and grandfather. According to his Uncle Ben, his father wasn’t a great fisherman. Yet ‘nobody loved [fishing] more.’

What makes a great fisherman, he continues to ponder? ‘Is it loving [fishing] more? Seeing more into it? Finding more that attaches you to the great themes of life and nature? Developing skills to out-perform others?

He remembers feeling overwhelmed when he caught his first brook trout in his aunt’s pond in rural Massachusetts. ‘One of the great drives for anglers is to see a fish because they are emblematic of the perfection of nature (italics mine).’

After asking what makes people fish, McGuane recalls his father’s and uncle’s aversion to using lead ‘in any form’ while fly fishing. Dry and wet flies and streamers sans lead were the only patterns worthy of fly fishing. ‘Lead was considered to be contrary to the spirit of things.’ Although his Uncle Ben scornfully described fly anglers who used lead as ‘booger-eating morons,’ McGuane sheepishly admits he carries split-shot in his vest. (His crass weakness would be forgiven by most contemporary fly anglers.)

McGuane insists ‘trout are not an insurgency, not something to be defeated.’ Rather, ‘they are creatures [with which] we establish a relationship. We enter into a dialogue with them the way old-fashioned dry fly purists [did]. We fish not to be productive, but in a way that seems right to us.’

McGuane refers to the 20th century Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga when he considers fly fishing in terms of fun, which is neither ‘frivolous,’ nor ‘superficial,’ but possesses ‘profound aesthetic qualities.’ Fun and play ‘ventilate our monotony,’ he says, quoting the philosopher. The first characteristic of fun is ‘freedom,’ which feeds ‘man’s imperishable need to live in beauty.’ Fly fishing is ‘rooted in the primeval soil of play.’

The consideration of fun leads McGuane to contemplate ‘the well-being of fish.’ Even the practice of catch and release involves ’mortality,’ he observes.

Then he turns his thoughts to the concept of home waters. Dismissing the importance of a passport to contemporary fly anglers with adequate means, he insists that, ‘abandoning home waters because you can spend more and fly farther is a low idea.’ (From reading his angling essays, it’s clear McGuane has done his share of fishing in exotic locales.)

In recent years McGuane has become ‘an avid spey caster.’ This elegantly graceful method of two-handed casting ‘passes the time’ between strikes, which can be days apart.

He recalls a day steelheading on the Bulkley River in British Columbia, when a couple of young fishermen in hoodies offered him a toke of ‘infamous BC bud.’ When McGuane declined, one of the young men looked at him askance and quipped, ‘How in the world can you fish for steelhead unless you’re stoned? There just aren’t that many bites.’ ‘I was already on the narcissistic high of spey casting,’ he replied.

We live in an era of speed and unprecedented distraction, when ‘money is deified,’ he asserts. Fishing is something of ‘an antidote,’ he adds, reminding us to ‘be mindful.’

He then reflects on the freestone creek he lives beside in Montana’s snow-driven ecosystem, contending that one of the ‘unintended consequences of fly fishing’ is gaining an ecological awareness with spiritual overtones. Fishing helps you ‘face failure with equanimity because so many of the parts of the experience fulfill us.’ He adds with a broad grin, ‘the uncertainties of fishing undermine all forms of smugness.’

McGuane pays respect to the growing number of women who are taking up fly fishing. He tells an anecdote about the bedside confession of an elderly woman who landed a monster Atlantic salmon years previously. With her last breath she taunts her son with the declaration: ‘You’ll never get a 50-pounder.’

As his talk winds down, McGuane observes that, ‘fishing is a good way to find out where you are. I’m learning my place on earth.’ Fishing breaks down the ‘malignant fantasy’ of an ‘imaginary firewall’ between man and nature. ‘Mankind needs a better way to approach his own survival.’

Recalling the last century, the most violent in recorded history, McGuane asserts, ‘all signs suggest we’re actually at war with the Earth itself.’ Unless something is done, ‘you can kiss cold-water fishing goodbye.’

Beginning his talk on a note of uncertainty, McGuane ends on a graceful note of optimism by remembering Sasha, a Russian fishing guide who bears the ‘fragility’ of three tours in the Chechen war: ‘But I’ll be OK, I’m with the river now,’ the guide told his American sport.

(There’s a lovely podcast of McGuane with Montana fishing guide and debut short story writer Callan Wink (Dog Run Moon: Stories) at New Yorker Radio Hour, #43: Summer in the City. They talk affectionately about the late Jim Harrison, among other topics.)