Writers rely on words to communicate with readers. But synchronicity occurs between writers and readers when experiences are shared. This happened as I was reading A Life with Words, a new memoir by Richard B. Wright.

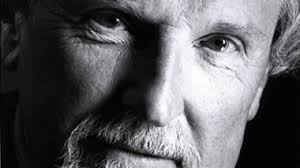

I have long admired Wright’s novels. He’s not only a fine novelist, he graduated from Trent University (where he was later awarded one of three honorary doctorates) as a mature student in 1972, the year I started there as a mature student.

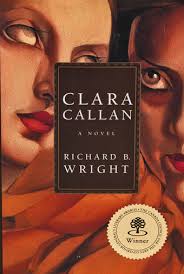

Wright’s multiple prize-winning Clara Callan, his best-known and most-celebrated work, is a worthy companion to Carol Shields’ masterwork The Stone Diaries. Interestingly, Wright applies his sympathetic imagination to the mind and body, heart and soul of two sisters. Shields exercises the same cross-gender sympathetic imagination in Larry’s Party.

Although Clara Callan won the Giller Prize, Governor General’s Award and Trillium Book Award, the St. Catharines-based writer is not a household name à la Atwood, Ondaatje, Munro and company.

Over the past 45 years, the 78-year-old author has written an impressive range of fiction beginning with a children’s book, Andrew Tolliver. His dozen novels in chronological order include: The Weekend Man, In the Middle of a Life, Farthing’s Fortunes, Final Things, The Teacher’s Daughter, Tourists, Sunset Manor, The Age of Longing. Clara Callan, Adultery, October and the intriguingly titled Mr. Shakespeare’s Bastard.

Wright’s The Age of Longing and Paul Quarrington’s King Leary are the two best literary novels about hockey ever published in Canada.

Published by Simon & Schuster Canada, A Life in Words is Wright’s first work of non-fiction. It won’t increase his cultural profile, but readers who appreciate his fiction will enjoy the memoir, as will aspiring writers who want to gain insight into the well of inspiration out of which fiction is drawn.

Written in the third person like Salman Rushdie’s 2012 memoir Joseph Anton, Wright’s memoir reads like a novel — graceful, understated and self-deprecatingly funny. The third-person narration also makes it an unusually sparse and modest account of one of Canada’s most accomplished novelists.

A third of the memoir — a disproportionately large portion in terms of the literary autobiographical norm — is devoted to Wright’s childhood and adolescence growing up in a working-class family in Midland, located in southern Ontario on the shore of Georgian Bay.

Readers of a certain age and background — those who grew up during the Second World War and the Cold War decade of the 1950s — will identify with Wright’s affectionate depiction of WASP (White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant) small-town Ontario. His delineation of the infiltration of American popular culture will bring back memories of radio and early television shows.

Very much A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, A Life with Words begins by recounting childhood anxiety. In hindsight the anxiety is innocuous — sinister nursery rhymes (When the bough breaks, the cradle will fall), menacing prayers (If I should die before I wake) and banal schoolyard indignities afflicted on the unsuspecting by vengeful classmates. Nonetheless they are the fabric out of which the adult writer is woven. Wright continued to suffer from anxiety, which he named the ‘red dog’.

I know of what Wright speaks. Until I was 10 years old, my family (mom, dad, sister and brother) lived in a tiny apartment above my maternal grandparents. My grandmother would sometimes babysit. At bedtime she would sit with us children in our dark bedroom, where she would smoke a cigarette, its small red flame pulsating with each draw, as she softly sang the sad lonesome dirge Show Me the Way to Go Home (I’m tired and I want to go to bed). If that didn’t put us to sleep she cautioned that the Boogeyman would come calling. The blend of forlorn song and threat was not exactly conducive to a peaceful night’s sleep.

Wright does not explore his fiction in detail or depth. This might disappoint readers who cherish Wright’s work and are anxious to get an up-close and personal assessment. Instead he touches on locations, circumstances and events that inspired or nurtured his novels.

For example we learn that he had an Aunt Clara and that the novel’s small-town setting is based on his maternal grandparents’ house and the village in which they lived and where Wright spent an idyllic week at the end of each summer during his childhood. Similarly he reveals how a brush with Evangelical religion when he was 10 was transformed into fiction in his 10th novel Adultery.

What is most interesting is accompanying Wright as he traces the formative elements that shaped the creative sensibility on which his literary life is built. He uses a childhood experience of shovelling snow as a metaphor through which to explore the process of writing, editing and rewriting.

He recalls how a Grade 11 English teacher — ‘a conceited little twit, but . . . a damn good teacher’ — opened the door to the power of language “to terrify or console.” He ends the memoir with the eloquent observation: ‘Without words we are reduced in our capacity to endure vicissitudes or express our wonder at being alive.’

I’m forever grateful to acknowledge that I had the identical experience in high school when a first-year English teacher exerted the same profound influence on my life. Although I was the class clown in a technical school with segregated classes, Mr. McGuire’s passion for literature shaped my life.

After graduating from high school and working a few weeks picking tobacco — remember when tobacco was the premium crop harvested along the north shore of Lake Erie? — Wright heads off to Toronto the Good to study radio and television arts at what was known at the time as Ryerson Institute of Technology. After graduating, he enjoys a cup of coffee at a weekly newspaper before landing a radio job in Barrie.

It is during this period he begins savouring the juicy fruits of sex. The detail with which he recalls these amorous adventures contrasts with the memoir’s overall reserve. But you can’t blame an author for retracing delicious memories.

Wanting to either write books or participate in the publication of books, he sends resumes to a dozen publishers before receiving a letter from Kildare Dobbs, senior editor at Macmillan of Canada. His time at the venerable publishing house furnishes creative fodder for The Weekend Man. This period marked a historic watershed in the development of Canadian literature.

Compared to the space Wright devotes to a humorous set piece detailing a martini-drenched lunch with a disillusioned advertising executive, the cameos of Dobbs and legendary Macmillan president John Gray seem paltry.

In 1962 Wright embarks on a whirlwind tour of Europe, just as U.S. president Kennedy and Russian president Khrushchev decide to play chess with the future of the world, which history remembers as the Cuban Missile Crisis. While in Dublin, Wright visits St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where the great Anglo-Irish satirist Jonathan Swift once served as dean.

It so happens I visited the Church of Ireland cathedral for Evensong in December 1998 during a terrible national crisis — the Marc Lépine mass murder at Montreal’s École Polytechnique.

Wright meets his wife Phyllis at Macmillan, and the couple and first of two sons spend a year off the grid in her parents’ house on the Gaspé, which allows Wright to complete his first novel.

He spends a brief period with Oxford University Press before summering with his family in England. Wright enrols at Trent University in his early 30s, while he and his family rent a cottage on nearby Chemong Lake until he graduates with a BA in English and history.

Predating writer residencies and creative writing programs, Wright decides to keep the wolf at bay by teaching at a private school, which frees up time for writing. Like Dunstan Ramsay in Robertson Davies’ Fifth Business, he lands a job at Lakefield College in the nearby village Margaret Laurence put on the Canadian literary map while living there and writing The Diviners. Meanwhile In the Middle of a Life is published.

Wright invokes the name of Davies a couple of times. Despite the difference in class and economic status, the writers share a common small-town Ontario background and Celtic heritage. He even applies for a job at the Peterborough Examiner when Davies is publisher and editor.

Davies was a big influence in my life, as well. The desire to write a thesis on the writer led me to graduate school.

In 1973 Wright accepts a job in the English department at Ridley College, a private boarding school in St. Catharines, and begins balancing a teaching career with his vocation as a novelist. He releases Farthing’s Fortune, which he succinctly describes as ‘a handbook for pessimists who laugh at the jests of Providence’ — a description worthy of the Old Master himself, Rob Davies.

He writes Final Things in 1979 to expunge the ‘rage and fears’ caused by the brutal murder of a 12-year-old shoeshine boy in Toronto. He dashes off The Teacher’s Daughter before writing Tourists after vacationing in Mexico with his old friend Dobbs. He develops Sunset Manor from a failed short story.

Wright suffers a crisis of confidence in the late 1980s which is ameliorated with the publication of The Age of Longing. Set in the Great Depression (‘for many, an open wound, a bad memory, a place [they] had escaped from but were still haunted by’), the novel is shortlisted for both the Governor General’s Award and Giller which, as it turns out, anticipates greater acclaim.

Wright’s masterwork Clara Callan is a return to his recurring theme of unmarried female school teachers. He recounts how the novel emerged by reprinting an essay, Finding Clara, he wrote for the Giller Foundation on the prize’s 10th anniversary.

After retiring from teaching in 2001 he published his most recent trio of novels.

I read A Life in Words in two days, wishing it were longer than its 200 pages. Wright is a quietly elegant writer. Here is an example of his clear, precise prose:

‘The American writer Bernard Mulamud once described writing a novel as a long voyage in a small room. The metaphor of a journey is certainly apt, but the voyager is often without a reliable map, or indeed any map at all; moreover, it is a journey that must be measured at least in months and more likely in years. Unlike the lyric poet, or the short-story writer, the novelist has no chance whatsoever of experiencing that epiphanic glow that might arise from completing something in a matter of hours or days. Like a long-distance runner, he has to pace himself, tempering his emotional reaction to a day’s work, becoming neither unduly elated over what he perceives to be terrific stuff nor unreasonably depressed over what looks like a wrong turning. All that, of course, is easier said than done. . . .’