Alex Colville was one of the Canadian artists I most admired. His unique existential realism appealed to me because of the quality of literary narrative that underlies and informs his work. Whether or not the artist intended, I have never been able to spend time with a Colville drawing, painting or print without trying to piece together the story to which he gave expression through his mysteriously engaging formal vocabulary.

I was deeply honoured to meet the artist when he visited the University of Waterloo in conjunction with an exhibition of drawings organized by Joe Wyatt (who at the time was curator of the university’s art gallery), in conjunction with the fine arts department. Having Colville walk me around the exhibition was a highlight of the three decades I spent as an arts reporter for the Waterloo Region Record.

I certainly could never afford an original work; but one of my prized possessions is a high-quality, photo-mechanical, limited-edition print of Seven Crows. To my knowledge it was the only lithographic series not produced in his studio which he approved and signed.

A new book of correspondence between the late artist and Jeffery Myers — a prolific biographer based in Berkley, California who has written books on Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Robert Frost, Edgar Allan Poe, Edmund Wilson, George Orwell, D.H. Lawrence and Joseph Conrad among others — has caused me to post a blog in celebration of Colville’s life and art.

Published by Sussex Academic Press, the new book has been saddled with the unwieldy title of The Mystery of the Real: Letters of the Canadian Artist Alex Colville and Biographer Jeffrey Meyers. I assume its awkwardly prosaic handle is turned towards an international readership unfamiliar with Colville.

Following is a couple of articles I wrote on the occasion of a memorable career retrospective mounted by the Art Gallery of Ontario in August, 2014. Interestingly the exhibition, simply titled Alex Colville, involved Andrew Hunter, another former curator of the University of Waterloo Art Gallery.

At 92, his death was not unexpected. But that doesn’t mean those who appreciated the art of Alex Colville were not surprised by his passing. Nothing really prepares us for the intersection of mortality and eternity.

When an artist as popular as Colville dies, we take it personally. It’s a death in the family, especially if the family extends beyond blood and country.

Before his death on 16 July, 2013, Colville was arguably Canada’s most popular artist — even though the artist received more critical renown in Germany than in his own country.

For people who enjoyed art outside the hallowed circle of professional specialization, Colville was an icon of serious Canadian art. Neither as confounding as Christopher Pratt, nor as enthusiastically dismissed as Ken Danby or Robert Bateman, he was viewed by many as our painter laureate.

His stature and legacy within the Canadian art establishment (gallery directors, curators, academics, commentators and critics) was less certain. He remained an irritating nettle in the backside of the cognoscenti.

Colville was due for reassessment even before he died. After all, his last major exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario was in 1982. His passing not only made re-evaluation more urgent, it made a full career retrospective possible. Surprisingly, the AGO was first off the mark with a 70-year, career retrospective of the artist who was born in Toronto on 24 August, 1920, educated at Mount Allison University and lived most of his life in small towns in the Maritimes — first in Sackville, N.B., then in Wolfville, N.S.

Considering that a mere year has passed since the artist’s death, the speed with which the gallery launched the exhibition is amazing, based on the time it normally takes large institutions to organize and mount ambitious exhibitions. No small credit goes to Andrew Hunter, the gallery’s curator of Canadian art since May 2013.

A practicing artist, writer and educator, as well as a curator who has mounted exhibitions in galleries across the country, Hunter is well known to Waterloo Region. He was director/curator of the University of Waterloo Art Gallery (renamed Render during his tenure), from May 2006 through December 2009, after which he served as adjunct faculty and researcher at the UW School of Architecture, from January 2009 through August 2011.

Hunter took time out during the special members’ viewing to discuss Colville – the man and the artist, his work and his influence. Even before the exhibition, neatly titled Alex Colville, opened to the general public, Hunter was encouraged by the response it was receiving. ‘People seem excited by the pairings between the paintings and the works in other disciplines including commissions, films and literature,’ he observed while sitting beside an AGO media staffer.

Hunter, who wrote both the introduction and the essay for the catalogue, describes the exhibition as ‘dense and content-rich.’ He insisted that it doesn’t draw conclusions about the artist other than to suggest some of the ways his influence seeped into other disciplines. ‘This is not a memorial. We are not closing the book on Alex Colville.’ Eschewing the ‘traditional, historical perspective,’ the exhibition sets out to answer the question: ‘why Colville is so important, now and in the future.’

Hunter has no patience with those who relegate Colville to a regional artist who remained insular and isolated from the world. Although the artist lived most of his life in the Maritimes, away from the so-called centres of high culture, he was ‘deeply connected to the world.’ Colville lived in university towns and maintained associations with a vast network of people, both in Canada and abroad. He had galleries and was collected in Europe, Hunter asserted. ‘He thought deeply about art, travelled widely and was interested in other disciplines. He did not withdraw, but was deeply engaged in the world.’

The Mystery of the Real confirms Hunter’s opinion, revealing an expansive thinker who was enthusiastically literary and unapologetically self-reflective.

Hunter confirmed Colville was ‘front of mind’ when he was hired by the AGO. ‘He was an artist with whom I thought we should be engaged. It seemed like the time was right.’ After the artist died, ‘it was important to do something now.’

Hunter described Colville as an artist of ideas. “He didn’t change the process of how he worked. Sure, there were some shifts, but it’s the ideas that engage us. Ideas that challenge us to think about the world we live in.’ It’s a mistake ‘to see Colville as simplistic,’ Hunter declared. ‘There are incredible layers of complexity in his work. He says a lot with a little.’

Again, verified by The Mystery of the Real.

Alex Colville might have died 13 months ago, but he has not been forgotten. The proof lies in the Art Gallery of Ontario presenting the eagerly anticipated Alex Colville, the largest show ever mounted devoted to the artist.

Curated by Andrew Hunter, the AGO’s curator of Canadian art, the exhibition subsequently travels to the National Gallery of Canada. The Ottawa gallery holds the largest collection of Colville works.

The exhibition features 170 works including notebook sketches, drawings, preparatory works, prints and paintings (watercolour, oil, tempera and acrylic). The primary works are supported by biographical films, video interviews and photographs.

Colville’s paintings are paired with the commissioned work of five contemporary artists in various media including David Collier, William Eakin, Tim Hecker, Simone Jones and Gu Xiong. Similarly, the paintings are presented in the context of literature and film, including contributions from Canadian writers Alice Munro and Ann-Marie MacDonald, in addition to filmmakers Stanley Kubrick and the Coen Brothers.

Colville’s work is well known. Completed in 1954, Horse and Train might be the most ubiquitous and most readily recognizable image ever painted by a Canadian. Although the artist is appreciated by many, the nagging question remains: how well is he understood?

What follows are a few thoughts and observations that arose as I perused Alex Colville. They are intended to encourage debate by opening some windows on the singularly unique world Colville constructed over an incredibly uniform and consistent career spanning seven decades.

Although his work is representational, Colville is not a realist as generally understood and classified. The paintings are thoroughly engaged with reality as visual metaphors rather than as exercises in verisimilitude. I believe they are best read as visual narratives, as enigmatic short stories that give shape to existential joys and anxieties, which are apprehended if not always made explicit.

Look closely at the paintings and you notice the breasts that defy gravity in Headstand, the way the canoe rests awkwardly on the man’s shoulders in White Canoe, the unrealistic way the splash is depicted when one of the four swimmers hits the water in The Swimming Race.

Colville’s paintings are precise, meticulously organized in terms of geometrical calculation and manipulation. Neither random nor spontaneous, they draw attention to their own lifelessness and deliberateness.

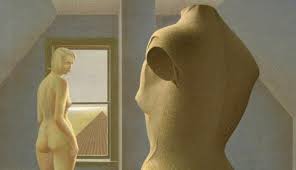

Although the figures are based on real people — most often his wife, Rhoda, or the artist himself — they are sculptural forms inhabiting dramatic space, creating vignettes arrested and frozen in time, evanescent moments held in the Eternal Now, the universal embodied and enacted in a specific place, everywhere and nowhere, for now and always.

The female nude in Coastal Figure is almost Henry Moore-like in its sculptural form. Look how the naked woman resembles the mannequin in Nude and Dummy. Colville desexualizes the female nude because he does not intend them as images of desire, but as embodiments of formal beauty.

It’s surprising, shocking even, how small the paintings are because of the size of the world they embody and reflect. How can existence be so modest in terms of scale?

As an artist, Colville possessed a fierce, uncompromising honesty. Look at Studio is a late self-portrait that courageously exposes the infirmities and reduced capacity that accompany old age. It’s a naked (literally and metaphorically) portrait of the ravages of time and the scars of mutability and mortality.

Much of his oeuvre is devoted to self-portraits, portraits of his wife, who by turns was his companion, soulmate, model and muse, and portraits of animals — domesticated (dogs, cats, sheep, horses) as well as wild (crows, coyotes).

Relationship holds Colville’s world together; it’s the mortar that binds. But often relationships are strained as if existence is a dance between togetherness (Looking Down, Refrigerator) and apartness (Living Room, Woman, Man and Boat, Boat and Bather, January). Sometimes the couple is connected in love and affection (Kiss with Honda, Soldier and Girl at Station); other times they seem strangers, he a voyeur and she unaware of the invasion of privacy (Woman in Bathtub, Dressing Room).

Colville’s paintings are not slice-of-life photographs in paint, but philosophical theorems expressed in line, shape and colour. They are pictorial arguments intended to evoke questions about the nature of existence and the existential struggle in which we are all engaged as humans with a finite lifespan.

His paintings are insistently philosophical, but not in an elitist, academic way. They remain accessible to all. As such, they are unsettling without being disturbing enough to be offensive — the familiar made slightly unfamiliar. Because we are not made uncomfortable enough to be pushed outside of our comfort zone, we share in the dynamic between artist, image and viewer.

Consequently we are not made to feel outside of the experience. We get it, the meaning that lies just behind or under the image, just beyond the picture frame. We experience the delightful shiver of recognition.

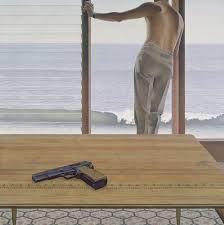

Colville’s paintings are a conscious effort to impose order on a chaotic universe (the full blunt of which he confronted as a war artist during the Second World War). But there’s a disconcerting sense of order shattering or disintegrating at any moment, like a stallion bolting (Church and Horse). Consequently, we feel a palpable sense of dread, menace, implicit violence, anxiety and angst. The danger is implied, anticipated, as if something could happen at any moment — suddenly, unexpectedly, randomly, without warning or caution.

In Pacific, showing a man turned away from a pistol on a table while looking out on an expansive body of water, and Woman with Revolver, showing a naked woman holding a gun while standing on a darkened stairway, something sinister is about to happen — or so we fear.

Conversely, in Seven Crows — an image that has fascinated me for more than 30 years of continuous contemplation — something sinister has already happened.

Colville was never a darling of the Canadian art establishment. Like the late U.S. ‘realist’ painter Andrew Wyeth, he posed problems for institutional art tastemakers. Popular in his own time, like Wyeth, rather than after the fact like the French Impressionists, Van Gogh or even The Group of Seven, Colville openly embraced his popularity.

Like Wyeth, he was conservative in temperament and Conservative politically at a time when artists were expected to be radical or apolitical. Moreover, he was overtly rather than covertly entrepreneurial. Both artists were classicists rather than Romantics in approach to their image-making.

Again like Wyeth, Colville bucked trends, fads and fashions by continuing to be a representational painter at a time when representation was spurned in favour of abstraction, non-objective and minimalist, colourfield painting; after which painting was eclipsed by photo-based work, conceptualism, installation and performance art.

But, like Wyeth, Colville not only persevered, he flourished. Proof of his artistic triumph is celebrated in Alex Colville. Let the reappraisal begin.

Below is a revelatory 1983 interview with Barbara Frum.