Bush land scrub land —

Cashel Township and Wollaston

Elvezir McClure and Dungannon

green lands of Weslemkoon Lake

where a man might have some

opinion of what beauty

is and none deny him

for miles —

Yet this is the country of defeat

where Sisyphus rolls a big stone

year after year up the ancient hills

picnicking glaciers have left strewn

with centuries’ rubble

backbreaking days

in the sun and rain

when realization seeps slow in the mid

without grandeur or self deception in

noble struggle

of being a fool —

A country of quiescence and still distance

a lean land

not fat

with inches of black soil on

earth’s round belly —

And where the farms are

it’s as if a man stuck

both thumbs in the stony earth and pulled

it apart

to make room

enough between the trees

for a wife

and maybe some cows and

room for some

of the more easily kept illusions —

And where the farms have gone back

to forest

are only soft outlines and

shadowy differences —

Old fences drift vaguely among the trees

a pile of moss-covered stones

gathered for some ghost purpose

has lost meaning under the meaningless sky

— they are like cities under water

and the undulating green waves of time

are laid on them —

This is the country of our defeat

and yet

during the fall plowing a man

might stop and stand in a brown valley of the furrows

and shade his eyes to watch for the same

red patch mixed with gold

that appears on the same

spot in the hill

year after year

and grow old

plowing and plowing a ten acre field until

the convolutions run parallel with his own brain —

And this is a country where the young

leave quickly

unwilling to know what their fathers know

or think the words their mothers do not say —

Herschel Monteagle and Faraday

lakeland rockland and hill country

a little adjacent to where the world is

a little north of where the cities are and

sometime

we may go back there

to the country of our defeat

Wollaston Elvezir Dungannon

and Weslemkoon lake land

where the high townships of Cashel

McClure and Marmora once were —

But it’s been a long time since

and we must enquire the way

of strangers —

— The Country North of Belleville

I first set eyes on Al Purdy in the early 1970s at a festival of Canadian authors hosted by Trent University, where I was an undergraduate with a passion for homegrown literature.

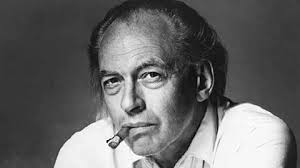

The late Canadian poet — who died in 2000 at the age of 81 — stomped into a common room with a stubby bottle of beer in one hand and a mangled stogie in the other. Resembling a longshoreman on sabbatical from the docks, the tall, gangling, dishevelled poet spotted another writer who he greeted by walking over an armchair and letting go a hearty, foghorn bellow of boisterous recognition.

It was a staged scene featuring the Purdy persona of public boor — a carefully crafted mask that disguised one of Canada’s great poets. His collected poems Beyond Remembering is one of the essential volumes in this country’s literary canon. No poet before or since has captured the deep cadence and profound silence of this country with more piercing authenticity. Not bad for a high school drop-out who taught himself the ‘craft or sullen art’ of poetry through a blue-collar ethic of determination, perseverance and the kind of hard work that leaves calluses on the palms of hands.

Like so many of the seminal writers who comprised the Canadian Literary Renaissance of the 1970s — from Margaret Laurence and Robertson Davies to Irving Layton and Earle Birney, not to mention critics Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan — Purdy has been lost to the latest generation of English students, intelligent readers and emerging literary scholars. A pity, this.

The resurrection of Al Purdy began in 2008 when an association headed by Jean Baird mounted a public campaign to preserve as a writers’ retreat the poet’s home on Roblin Lake across from Ameliasburg, in Prince Edward County. With the help of fellow peoples’ poet Milton Acorn, Purdy cobbled together an A-frame cottage from recycled materials and homemade wine. He and his wife Eurithe lived there for 43 years. It was the still point in the turning world of Purdy’s writing, spanning fiction (A Splinter in the Heart), memoir, essay, criticism and, most significantly, poetry.

Purdy’s resurrection continues with Al Purdy Was Here, an affectionately elegiac film directed by Canadian arts journalist Brian D. Johnson, who in 2014 retired after more than two decades as film critic for Maclean’s magazine. The documentary, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival earlier this fall, screens December 10 at the Original Princess Cinema in Waterloo in partnership with Words Worth Books.

Purdy no doubt would get a kick out of a film critic becoming a cinematic director. He would most assuredly have more time for the director than the critic. For his part, Johnson doesn’t see much of a difference. ‘Good filmmakers are critics by necessity,’ he acknowledged over the phone. The poet would also be bemused by how the film ‘happened organically.’

Johnson admits he didn’t know much about Purdy, having never read the poetry before the film project. He was introduced to the poet through his wife, author Marni Jackson. Jackson read Purdy’s poetry in her youth and later interviewed him for TVO’s much-missed literary interview program Imprint. In 2013 she worked on an event at Toronto’s Koerner Hall staged to raise funds to save the A-frame and underwrite the residence program. The event was filmed and Jackson asked her husband to edit the footage.

Johnson says he became fascinated by Purdy, who he described as ‘charismatic, eccentric and enchanting. I never grew tired of him.’ Initially he agreed with his wife’s suggestion that Purdy ‘would be a great subject for a play’. (In fact she wrote a draft that was workshopped while the film was being made.) It was after Johnson thought about blending Purdy’s poetry with music that he became convinced a full-length feature documentary was not only possible, but appropriate. ‘Purdy is joined at the hip with contemporary singer/songwriters who are now more famous than poets. I thought a songbook would be the key to making a film.’

Johnson intended the film as a companion to The Al Purdy A-Frame Anthology, a collection published to raise funds, featuring selected poems by Purdy and others, along with essays, letters, anecdotes, cartoons, remembrances and architectural drawings, floor plans and archival photographs.

Happily, Johnson’s modest intentions grew into a film of substance that not only pays homage to Purdy, but recalls a time in Canada when poetry — and by extension, literature, arts and culture — mattered. Moreover, it contributes to the legacy of Purdy as one of the most enduringly eloquent voices in the poetry that is Canada.

The film is anchored by archival photos and film footage of Purdy, who returns in all his glorious contradictions, combativeness, foils, flaws and contrariness; and Eurithe, who at 90 seems to be carved out of the raw resilient country north of Belleville celebrated in her husband’s poetry. Both make for captivating and compelling viewing.

But there is more, much more. Al Purdy Was Here sheds light on some biographical skeletons that are not only surprising but shocking. There also are:

• readings of Purdy poems and reminiscences by CanLit heavyweights Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Joseph Boyden, Stephen Heighton and Leonard Cohen, in addition to Gord Downie (of the Tragically Hip) reciting one of Purdy’s most popular poems At the Quinte Hotel;

• insights by leading Purdy scholar Sam Solecki (author of The Last Canadian Poet: An Essay on Al Purdy) and fellow poets George Bowering and Dennis Lee, one of Purdy’s earliest and most eloquent admirers;

• songs by Neil Young and Bruce Cockburn, Sarah Harmer, Tanya Tagaq and Doug Paisley;

• recollections of Katherine Leyton, the 32-year-old Toronto poet selected in 2014 as the A-frame’s first writer-in-residence.

Johnson says the film is more biographical than he intended. But he insists he didn’t want it to be hagiography ‘as heroic a figure as [Purdy] is.’ He adds that he didn’t want it to be ‘too adoring’ in keeping with the poet’s character. ‘He didn’t like flattery.’ The director astutely acknowledges that however ‘dark’ our view of Purdy becomes as a result of the film, he remains a compelling figure that draws our forgiveness.

It’s impossible to view Al Purdy Was Here and not read the poetry, whether as introduction or as reacquaintance. ‘Al’s poetry still lights a fire under people,’ Johnson observes. As for the film, it captures the voice of the land (the epitaph on the poet’s grave) which transcends time and place because it’s so deeply imbedded in the rich primordial soul of this northern landscape.

Across Roblin Lake, two shores away,

they are sheathing the church spire

with new metal. Someone hangs in the sky

over there from a piece of rope,

hammering and fitting God’s belly-scratcher,

working his way up along the spire

until there’s nothing left to nail on—

Perhaps the workman’s faith reaches beyond:

touches intangibles, wrestles with Jacob,

replacing rotten timber with pine thews,

pounds hard in the blue cave of the sky,

contends heroically with difficult problems of

gravity, sky navigation and mythopeia,

his volunteer time and labor donated to God,

minus sick benefits of course on a non-union job—

Fields around are yellowing into harvest,

nestling and fingerling are sky and water borne,

death is yodeling quiet in green woodlots,

and bodies of three young birds have disappeared

in the sub-surface of the new county highway—

That picture is incomplete, part left out

that might alter the whole Dürer landscape:

gothic ancestors peer from medieval sky,

dour faces trapped in photograph albums escaping

to clop down iron roads with matched grays:

work-sodden wives groping inside their flesh

for what keeps moving and changing and flashing

beyond and past the long frozen Victorian day.

A sign of fire and brimstone? A two-headed calf

born in the barn last night? A sharp female agony?

An age and a faith moving into transition,

the dinner cold and new-baked bread a failure,

deep woods shiver and water drops hang pendant,

double yolked eggs and the house creaks a little—

Something is about to happen. Leaves are still.

Two shores away, a man hammering in the sky.

Perhaps he will fall.

– Wilderness Gothic

Al Purdy Was Here

Original Princess Cinema

December 10

7 pm