I just need some place where I can lay my head

Hey, mister, can you tell me, where a man might find a bed?

He just grinned and shook my hand, ‘No’ was all he said.

Take a load off Fanny, and you put the load right on me

— The Weight

‘Till Stoneman’s cavalry came and tore up the tracks again

In the winter of ’65, we were hungry, just barely alive

By May the tenth, Richmond had fell, it’s a time I remember, oh so well.

The night they drove old Dixie down, and the people were singin’ they went

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

— The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down

I bought my first albums by solo artists in 1967. I was 16 and was introduced to both by Larry McGuire, my Grade 10 English teacher. The first was Lightfoot, released the previous year; the second, The Songs of Leonard Cohen, released in Canada’s Centennial year. I remain deeply grateful.

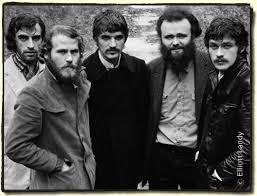

A year later I bought my first album by a group. It was recommended by my younger brother Steve. It was not by The Beatles or The Dave Clark Five or The Rolling Stones, but by five musicians known simply and audaciously as The Band.

Music From Big Pink was unlike anything I had ever heard. A collective creation in every sense of the term, it was complex, mysterious and haunting, a rich blend of different styles and traditions that formed the bedrock of popular music — a vibrant tapestry of folk, country, gospel, blues, mountain music, rockabilly, improvisation, even classical, not to mention good ‘ol butt-kicking rock ’n’ roll.

The songs, written or co-written by multiple Band members, had a unique literary quality, like old tales passed down through generations and retold around the hearth late at night. Simultaneously, they were wholly and completely new — revolutionary, experimental, sophisticated, progressive, fresh, urgent, innovative. In narrative thrust and character portrait, metaphor and symbol, they resembled Bob Dylan’s arcane and cryptic songs.

The lead vocals sounded seamlessly interchangeable (it took many listens before you recognized who was singing when). The harmonies were intricate and layered, off-the-wall and from left field, held together by a weird and wonderful orchestration of hitherto unheard of sound.

There were the familiar guitars, drums, electric bass and piano; but the Anglican church organ, clavinette and accordion; horns including sax, trumpet, trombone and tuba; and other sundry acoustic instruments including mouth harp and mandolin had no conventional voice in rock music. The musicians traded instruments like they were hockey cards among boys in a school yard.

The effect on the listener: like being deaf and suddenly hearing for the time.

Although cut from the deep roots of American music, four of the musicians came not from the United States, but from Southwestern Ontario — Robbie Robertson from Toronto via the Hebrew mafia and Six Nations Reserve, Rick Danko from a tobacco farm outside of Simcoe, Richard Manuel from small-town Stratford and Garth Hudson from the forks of the Thames River in London. The four were anchored by the lonewolf American, Levon Helm from the Arkansas Ozarks.

A year later The Band released its eponymous sophomore album. Coupled with Music from Big Pink, the pair constitutes a high-water mark in American music. They define what became known as Americana roots music. Just think about these titles: The Weight, Chest Fever, This Wheel’s On Fire, I Shall Be Released, Across the Great Divide, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, Up On Cripple Creek, Whispering Pines, Look Out Cleveland, The Unfaithful Servant. These and others are not only classic, they are immortal.

The group was never able to repeat the sheer brilliance and majesty of this singular achievement. But glimpses of greatness appear on all subsequent releases — Stage Freight, Cahoots, Northern Light-Southern Cross, Islands and Moondog Matinee, a collection of covers. Meanwhile, Rock of Ages remains one of the best live rock albums of all time.

The Band brought the curtain down in grand style on American Thanksgiving in November 1976 with The Last Waltz, the best music documentary ever filmed thanks to celebrated director Martin Scorsese. They had been together 15 years, first with Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins, then with Dylan. They famously — or perhaps notoriously — accompanied the future Nobel Prize for Literature recipient when he crossed the great divide from acoustic folk music to electric rock in 1966, causing fans from around the world to shout and scream indignities and throw tomatoes — and worse.

The Band continued in various configurations sans Robertson and later after Manuel’s death, but it wasn’t the same. The music continued but the magic was gone.

Robertson gained the most recognition post-Band; but all the musicians continued making music one way or another. Manuel, Danko and Helm eventually died, leaving Hudson and Robertson the last survivors because they were best able to resist the seductively destructive temptation of booze and drugs.

I first saw The Band perform live as a fan when they opened for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young at Toronto’s Varsity Stadium. They were wonderful. I still see them on stage, in my mind’s eye, rocking away the late afternoon and early evening. Jesse Colin Young was also on the bill.

I saw The Band, sans Robertson, play Lulu’s Roadhouse when I was an arts & entertainment reporter at the Waterloo Region Record. I also reviewed a concert at Stratford’s Festival Theatre — a kind of homecoming for Manuel, the first Band member to die too young. I had the privilege of talking to Danko over the phone from his home in Woodstock, in rural upstate New York, prior to the concert. He was a salt-of-the-earth delight, making the conversation a career highlight.

The Band has been pretty well served by a handful of musical biographies beginning with Barney Hoskyns’ Across the Great Divide: The Band and America (1993) and including Kitchener music writer Jason Schneider’s Whispering Pines: The Northern Roots of American Music. . . From Hank Snow to The Band (2009). We also have Helm’s incendiary memoir This Wheels on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of The Band (1993), in which he condemns Robertson for allegedly conniving to steal copyright to The Band’s catalogue.

Now we have the last word from inside The Band — Robertson’s splendid memoir Testimony. Given his personality and temperament, it’s unlikely Hudson will write a book. I luxuriated in the rich, lyrical prose for more than 500 pages. I put down the book fully satisfied, but I couldn’t help myself from wanting more.

Anyone who has ever heard Robertson talk will recognize his voice immediately. Reading Testimony is the equivalent of sitting down with the guitar ace and gifted songwriter over a pint as he weaves an utterly magical adventure of falling in love with music, joining Hawkins’ touring band The Hawks at 15 and becoming the potent creative force that guided The Band to greatness.

Robertson credits his First Nations blood for both his extraordinary memory and his elegant storytelling. If his songs don’t convince you of these gifts, Testimony surely will. Like all good authors, not to mention musicians, Robertson writes with his ear, keen to the rhythms, syncopations and cadences of words.

Unlike Helm, Danko, Manuel and Hudson, all of whom lived for music and were obsessed with making music, Robertson was the intellectual in the group, interested in literature, visual art and film. Compulsively reading film scripts over the years helped shape his songs, with their quality of cinematic storytelling, as well as his memoir.

In contrast to many songwriters who are not particularly eloquent when it comes to discussing music — Dylan and Gordon Lightfoot are two examples who come readily to mind — Robertson is a poet when it comes to assessing, evaluating and judging musicians and their music. His thoughts on music as expressed in Testimony are by turns engaging and intriguing. His devotion to all things musical is infectious.

Here’s a representative passage, when he first saw one of his heroes, the legendary Howlin’ Wolf, perform live:

We entered a music haven: a combination bar, restaurant, dance hall and juke joint. The ordour of stale cigarette smoke, perfume, liquor and spicy food hung thick in the air. . . Wolf and his band were already in the middle of their set, sweat glowing on their faces. Wolf’s stage attire was a white shirt and dress pants, but on him it looked like straight-arrow blues. Above the stage a blue spotlight shining down on his face made him look like a haunted man, but this was no voodoo; this was hoodoo and the spirit of the ‘new blues,’ different from the traditional folk blues of Josh White or Big Bill Broonzy. This was down, dirty and hard.

I was tripping over myself trying to get closer to that sound and fury. Wolf’s vocal style came from another planet, sliding from his big growling’ tone into his pinched bullhorn stinger, then just as quickly lifting us with his hoot-owl falsetto. And those guitar parts from Hubert Sumlin, king of the blues riff — to hear them live was like hearing them for the first time. On Howling’ Wolf’s records the music came bursting from the speakers with a powerful authority, but when the band played live it had a surprisingly delicate blend. All the parts sounded beautifully balanced.

Here in capsule form is a glimpse of what Testimony offers. The crystal-clear memory recall that plants you firmly in a specific place and time; the mood and atmosphere of the here and now, immediate and direct; the deep knowledge of music and its rich history; the descriptive power, with its subtle nuances of metaphor and imagery, that sweep you away on the transcendental wings of music. Moreover, the description of Wolf’s band performing live could just as easily apply to The Band.

Robertson’s recollections of musicians unfold like a Who’s Who of the 1960s and 70s. Far too many to delineate save for a tantalizing taste: The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and ‘Belfast Cowboy’ Van Morrison, in addition, of course, to Dylan, a dear friend of Robertson’s.

The Band made its reputation mining the mythology of Americana. But with the exception of Helm, the four other musicians were introduced to music as kids growing up in Southwestern Ontario. Moreover, all five honed their craft not in the hills and hollers of rural America, but on the bar circuit of southwestern Ontario — with and without Hawkins, the shrewd, calculating musical wild man from Arkansas who introduced rockabilly to the Great White North.

While Hawkins is generally credited with assembling the musicians who eventually became The Band, according to Robertson, he and especially Helm, Hawkins’ musical right-hand, were responsible for bringing Danko, Manuel and Hudson into the fold.

Robertson devotes more than one-fifth of his memoir to these early days and they make for fascinating reading — from London’s Brass Rail to Grand Bend’s Imperial Hotel and everywhere in between. We get an up-close and personal look at what the music scene in Southwestern Ontario was like in the 1960s.

As for Robertson himself, he lovingly recalls his roots including Dolly, his beautiful Mohawk mother from Six Nations; his assumed, abusive father Jim Robertson; his deceased, Jewish blood father; and his Jewish uncles, one of whom did time for criminal activities involving one of Canada’s most notorious gangsters. He proudly shows us the family man married to Moninique, a beautiful French-speaking journalist from Montreal who he ‘met in Paris in the springtime,’ as well as daughter Alexandria and son Sebastian.

But what really makes Testimony so compelling is the generosity of spirit and deep, abiding affection for his Band mates. He seems to carry no resentment towards Helm, who played the role of a big brother to Robertson for many years, even after publicly dressing down the younger musician. It’s clear that before booze and drugs entered the picture, The Band was a sepia portrait of brotherly love. The term ‘bromance’ doesn’t do justice to the respect, admiration and affection they shared.

Of course, we are left with Robertson’s take on the destructive forces that eventually ripped The Band apart. We get his view on what happened with respect to the copyright issue that embittered Helm. He claims he bought out the others fairly and squarely when they needed money. He’s very persuasive; but there’s nobody left to contradict, refute or rebut him.

Testimony is an emotionally resonant read. I wept through much of Robertson’s recollection of The Last Waltz at San Francisco’s Winterland and his final portraits of his Band mates. It’s heart-wrenching and heartbreaking. His enduring love is poetically palpable.

Here’s a few words on each of his musical brothers in arms:

Rick — His support in music and in life was unparalleled in this group. You never even had to look around: Rick had your back come rain or shine. And boy, what an ear! He could hear intricate intonations and parts like he had a dog’s super-hearing. He was king of harmonies in the Band, but not because he studied harmony or read music; it just came perfectly natural to him. . . He had no idea how incredible I thought (he) was. . . He evolved into an incredible force in the Band’s machine.

Richard — Man, oh man, Richard could break your heart, either with his voice, sounding like it was on the verge of tears at times or with his deeply sensitive personality. He had such a rich tone. He could sing lower and higher than anybody in the Band, which made us refer to him as ‘our lead singer.’ He didn’t like that. . . We were awestruck by his power and soulfulness.

Garth — Garth was a teacher. . . An inspiration in showing how much a musical instrument has locked inside of it and how much you can truly get out of it. . . I savoured Garth for turning me on to the glorious sounds of Anglican choirs, Greek and Arabic sounds with rhythms accompanying hip-rattling belly dancers, classical music maestros and their masterpieces (some through Glenn Gould’s piano), jazz masters’ unique tones and techniques. I couldn’t get enough of it and it broadened my sonic horizons as far as the ear could see.

Levon — The very first time I saw Levon play, when I was 15 years old, it struck me there and then: God only made one of those. He was a star already. . . you couldn’t take your eyes of Levon. Ronnie (Hawkins) knew it too; he danced in front of him, sang in his direction and looked to him for musical cues, while Levon played eighth notes on the kick drum, the cymbals and the snare, with a backbeat on the toms like a locomotion. All the while laughing until everybody joined in. I had never seen anything like it, and still haven’t to this day.

At bottom Testimony is a love letter to Richard, Rick, Garth and Levon who, with Robbie Robertson, were and always will be The Band.

The narrative beauty of Testimony begs the question: will Robertson continue to trace his journey in music with a sequel, picking up where The Last Waltz left off? I certainly hope so!

Meanwhile, thank you Robbie.

Watch The Band performing Up on Cripple Creek from The Last Waltz on YouTube: